Woodmere Annual show: A vast art portrait of the city

In recent years, the juror or jurors of the Woodmere Annual have been encouraged to tweak Philadelphia's largest, most prestigious juried exhibition. But this year's decider, the painter and Tyler School of Art professor Odili Donald Odita, was the first to take up the museum's offer of giving the annual a theme.

In recent years, the juror or jurors of the Woodmere Annual have been encouraged to tweak Philadelphia's largest, most prestigious juried exhibition. But this year's decider, the painter and Tyler School of Art professor Odili Donald Odita, was the first to take up the museum's offer of giving the annual a theme.

From the outset, Odita decided that his selections would reflect Philadelphia's vitality as a city and its growing importance as an art center. Most specifically, they would offer visual evidence of how living here affects artists' vision for their art.

The "Woodmere Annual: 75th Juried Exhibition - The Condition of Place" comprises works by 68 artists, culled by Odita from more than 400 artists' submissions. Think of it as an enormous portrait of Philadelphia rendered in paintings, photography, sculpture, and video.

The most stylistically diverse annual since William Valerio's arrival as director of the museum in 2010, it literally goes where previous annuals have not: on top of the grand piano and the circular sofa in the Katherine M. Kuch Gallery (also known as the rotunda), on the walls of the staircase leading to the rotunda's upper level, and into the museum's historic Parlor Gallery. It also has far fewer recognizable names than past annuals have had, making me wonder whether Odita made a point of not overlapping with previous exhibitions. Fair enough.

Walking through this annual can be like navigating the city, an effect I'm sure Odita worked hard to achieve. Have you noticed all the construction zones from Kensington to Center City? He has created a few here, but they're fun, not frustrating.

Karyn Olivier's two sculptures, in particular, set off this strategy to a T. In the first gallery, visitors must get around Concrete block (New Architecture), Olivier's amusing wall of cinder blocks inset with mirrors, in order to see the works behind it. In the rotunda, Olivier's Winter Hung to Dry, an enormous bundle of colorful sweaters, pants, scarves, and other articles of her winter wardrobe draped over a steel cable, similarly interferes with a view of the paintings and sculptures behind it. No matter, it sets the tone for Odita's annual.

Some works occupy space as if they were only temporary, perhaps to remind viewers of the city's ever-shifting landscape and demographics. Kara Springer's Untitled, a huge rectangular color photograph of what appears to be a crumbling white wall, is casually propped against a gallery wall. Maria Leguizamo's Untitled (Table) Part I, a wood assemblage that suggests a teetering table, has an air of joyful abandon.

Lydia Hunn's River City, a copier print on board and plywood, is hung unusually high, a decision I thought might have something to do with the optimism and affection embodied in this small piece symbolizing Philadelphia. Another of Hunn's modest works, Home, a minute lead sculpture of front steps leading to nowhere, sits all alone on the floor inside a recessed sculpture niche, posed as a victim of gentrification.

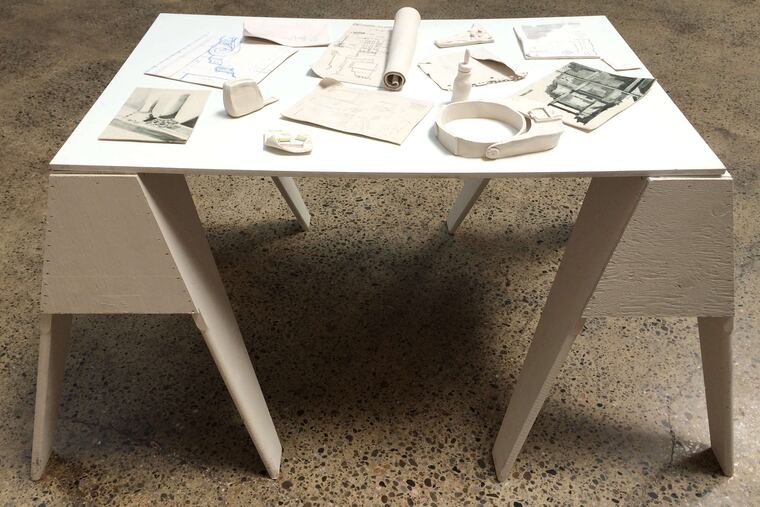

In a work titled Liquid Architecture, architectural renderings and objects (a tape measure, a Wite-Out bottle, and a magnifying visor) arranged on a work table near the middle of the rotunda look like they've been momentarily left behind by an architect. This is the remarkable work of Jacintha Clark, who creates her scenes entirely of hand-built, hand-painted porcelain.

For years now, the museum has been showing the works of jurors in the annual show. Odita, whose own patterned, vividly colored paintings of geometric zigzags hang in the rotunda, went overboard in his selections of other artists' large, colorful abstract paintings, several of which are too much alike - and, at least to this gallerygoer, not particularly representative of the Philadelphia gallery scene. Two exceptions are Mark Brosseau's small abstract Léger-and-Pop-Art-influenced painting, Positive, and Moira Connelly's introspective, painterly Untitled.

Odita's choices of paintings that combine abstraction, representation, materials, and writing suit his theme better, among them Belly of My Mind, Corinna Cowles' painting on a red-checkered plastic tablecloth featuring drips and graffiti; State of Mind, Alex Echevarria's witty evocation of a Home Depot or Lowe's garden center (I think); and a mixed-media painting on canvas and the wall around it by Raphael Fenton-Spaid, titled Spaghetti and Snowballs.

Clearly, Odita is an omnivore of good, unpretentious painting, whatever its style. The representational paintings he has selected are the unexpected stars of his annual. Mary Henderson, whose painting Walnut Street, depicting a typically assorted crowd of Philadelphians on the city street, reminded me of the Liberty Day parade of Blow Out, Brian De Palma's terrifying thriller set in Philadelphia. Late Winter, Laurel Hill Cemetery Ridge, Patrick Connors' unexpectedly steep uphill view of Laurel Hill Cemetery, in which monuments are rendered minuscule against a brilliant deep blue sky, is a sublime, elegiac paean to Philadelphia's formidable past - but also inspiration for new interpretations of the city.

Through Aug. 28 at Woodmere Art Museum, 9201 Germantown Ave., 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Thursdays, 10 a.m. to 8:45 p.m. Fridays, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sundays. Tickets: $10 general; $7 seniors; free for children and students with ID. Information: 215-247-0476 or www.woodmereartmuseum.org.