Sumerian scholars coming to Penn for rare event

Beginning Monday, Philadelphia will become the center of the Sumerian universe when nearly 300 Assyriologists descend on the Penn Museum for four days of hobnobbing, scholarly presentations, receptions, and Sumerian scuttlebutt.

Beginning Monday, Philadelphia will become the center of the Sumerian universe when nearly 300 Assyriologists descend on the Penn Museum for four days of hobnobbing, scholarly presentations, receptions, and Sumerian scuttlebutt.

The Penn Museum at the University of Pennsylvania will be hosting the 62nd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, the worldwide association of scholarly Mesopotamian enthusiasts, and a very big deal indeed. It is only the fifth time since its 1950 founding that the organization has held its annual gathering in the United States, and the second time it has been to Penn.

"Hosting this international conference at Penn is a great honor," said conference coordinator Grant Frame, associate curator in the Babylonian Section at the Penn Museum, and associate professor of Near Eastern languages and civilizations.

It provides, he said, a "wonderful opportunity for Penn and the Penn Museum to share with colleagues both our history of ancient Near Eastern research, and our current efforts, which take place in libraries, archives, and in the field."

The theme of this year's conference, "Ur in the 21st Century CE," may at first seem nonsensical, since the great city of Ur, in what is now southern Iraq, first rose to prominence in the third millennium BCE and was mostly empty by 400 BCE.

But work at Penn, most notably an ambitious digitization project, is now making it possible for scholars to venture into the leavings of Ur online in a way never before possible.

What was dead and buried 2,500 years ago is being reanimated in virtual space at www.ur-online.org.

That scholars at Penn are spearheading this project is more than appropriate. From 1922 to 1934, Penn and the British Museum jointly sponsored excavations at Ur that uncovered the city's famous ziggurat complex, its densely packed private houses, and spectacular royal graves. Half the finds from those excavations, led by Sir Leonard Woolley, are housed in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, with the other half shared equally between the British Museum and the Penn Museum.

Earlier, in the late 1800s, the Penn Museum sponsored four archaeological expeditions to the ancient ruins of Nippur, northwest of Ur. Nippur was the seat of the Sumerian god Enlil, ruler of the cosmos.

The artifacts from Ur and Nippur have provided Penn with one of the greatest holdings of ancient Mesopotamian artifacts in the world. Penn's scholarly riches include 25,000 to 30,000 clay cuneiform tablets alone, plus statuary, vessels, jewelry, pots, and other materials.

The conference will touch on a wide range of subjects, with session topics covering "Sorts of Gold, Sorts of Silver from the Royal Tombs of Ur, Mesopotamia"; "Babylonian Astronomers Predicted Lunar and Planetary Positions Using Iterated Maps"; "Forerunners of Deterministic Chaos"; and even "New Light on the Paleography of the Early Dynastic Umma Region."

Given the richness of the Penn collection, there will be much attention paid to Sumerian texts. Penn holds what conference organizer Frame characterizes as "the most important collection in the world of Sumerian literature."

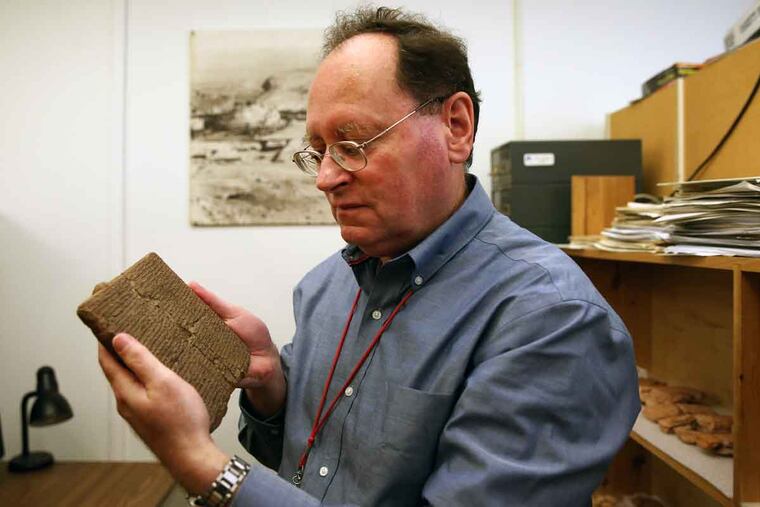

He held out a dark ochre clay tablet the size of a paperback book, one of a series of tablets on which ancient scribes impressed The Epic of Gilgamesh. This, Frame said, is "the Old Babylonian" version of Gilgamesh from about 1700 BCE, not the new Akkadian version, more familiar to students of Mesopotamia, that emerged at least half a millennium later.

He shows another small clay block on which are impressed diagonal strokes and geometric shapes. It is, he says, a fragment of the Sumerian account of the great flood, 1700 BCE, found at Nippur. Noah is known as Ziusudra in this account.

It is created in, essentially, hardened mud, the glory of Iraq and the glory of archaeologists. These hard-clay tablets are virtually indestructible. They contain, Frame said, everything from stories to medical prescriptions for poultices, receipts for sheep sales, and The Epic of Gilgamesh.

"Iraq had no natural resources except for mud," Frame said. "Egypt had lots of things - gold, copper. Iraq had basically nothing, and they built a fabulous civilization there in a truly inhospitable climate. It's amazing, the achievement of the people of ancient Iraq."

Sharing that achievement is part of what drives the Ur-online project.

William B. Hafford, manager of the Ur digitization project, said the point was to bring the vast amount of material excavated at Ur and housed at the Iraq National Museum, the British Museum, and Penn together online.

"Physically, I don't think the artifacts will ever be in the same place again, but they can be - in a virtual environment," he said.

Several years into the project, thousands of artifacts, with images and at least partial descriptions from the field, are already online.

The project has been largely funded by $1.7 million from the Leon Levy Foundation. Penn has raised an additional $600,000 and is looking for more to continue.

"Anybody who wants to do spears or mace heads or almost anything else from [Ur] can gather that information much more quickly" through the online site, Hafford said. "They can begin to think about it and begin to do the really important work of trying to understand how people lived."

215-854-5594@SPSalisbury