Arundhati Roy's long-awaited new novel: Overstuffed, disappointing

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, a novel whose nonchronological storytelling techniques and repeated tangents recall Roy's first book, marks her eagerly awaited return to fiction.

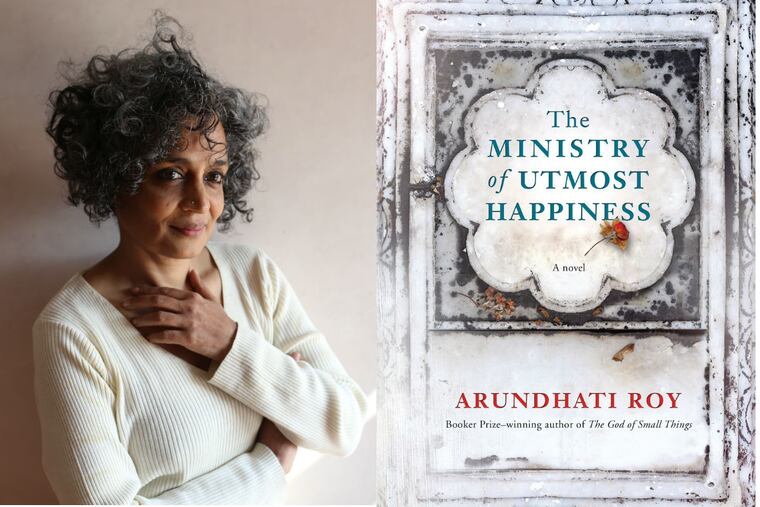

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

nolead begins By Arundhati Roy

Knopf. 454 pp. $28.95 nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Rayyan Al-Shawaf

nolead ends

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, a novel whose nonchronological storytelling techniques and repeated tangents recall Roy's first book, marks her eagerly awaited return to fiction.

It's a disappointment. Not because of the story's protagonists, who possess a captivating quality, or their travails, which exercise a magnetic pull.

The problem is that Roy subordinates these features to her main undertaking: political commentary of a kind more strident, sustained, and wide-ranging than that in her 1997 novel The God of Small Things, which won the Man Booker Prize.

Roy trains an unwavering light on the hidden ignominy of what is often regarded simply and reductively as "the world's largest democracy."

The author's beef with her native India is large enough to be sliced into several chunks. Chief among them is, as one character puts it, "the saffron tide of Hindu Nationalism," which "rises in our country like the swastika once did in another."

An additional issue, one predating the recent upsurge of Hindu fundamentalism in officially secular India, is the country's subjugation of Kashmir, a state home to a largely separatist-minded Muslim majority.

Roy enlists Tilo, a headstrong and enigmatic woman romantically involved with quietly charismatic and constantly hounded militant Musa, to introduce the reader to the saga of Kashmir.

Yet, instead of proceeding to convey the territory's agony through Tilo and Musa's relationship over the decades, Roy too often pans back, reducing the couple to a speck on a landscape she tries to depict in its entirety, or zooms in on other characters, who pop up to demonstrate the cruelty of India's policies only to vanish immediately thereafter.

This approach defines much of the novel. It enables Roy's forays into everything from the persistence of (illegal) caste discrimination in Indian society to the displacement of indigenous Adivasi tribes by mining companies to the plight of the uncompensated victims of the 1984 Bhopal poison gas leak.

The overall result is diffuse and messy, despite the legitimate grievances of the many groups Roy spotlights and the laudability of her social conscience.

Admittedly, Roy adopts a less desultory tack in the book's early chapters, where she relates the tale of Delhi native Aftab, who comes to be known as Anjum.

As a teen, Anjum, a hermaphrodite (the author's own usage) whom Roy fashions into an intriguing yet never exotic character, enters a demimonde of ancient and defiantly proud lineage; she moves into a dilapidated house inhabited by Hijras, biological males who identify as women.

Anjum remains in the Hijras' company for decades, "with her patched-together body and her partially realized dreams," after a botched operation to make her a woman.

A Delhi graveyard ultimately brings together Anjum and Tilo - while they're still alive. That they and other misfits/outcasts find solace only by taking up residence among the dead, where they minister to one another as well as "a Noah's ark of injured animals," makes for searing social criticism.

It also merges the two main story lines and clarifies the novel's ironic title.

But this is too little too late. Despite an alluring mix of fey beauty and real-world grit, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness remains overstuffed, overly expository, and overlong.

Rayyan Al-Shawaf is a writer and book critic in Beirut. This review originally appeared in the San Antonio Express-News.