We Want You: Propaganda posters

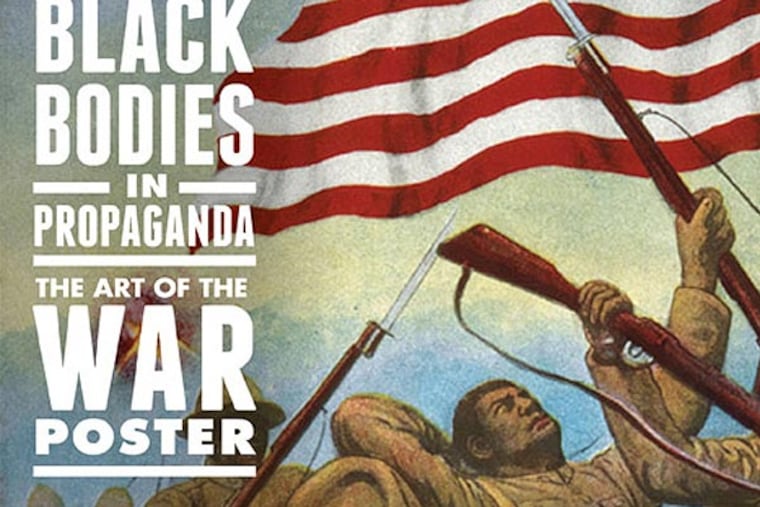

The Penn Museum presents a personally curated collection of 33 propaganda posters that chronicle our military history.

During World War I, two soldiers on sentry duty, Needham Roberts and Henry Johnson of the 369th Infantry, battled for their lives and the lives of their fellow soldiers, when faced with a German raiding party of 20 men. Without time to alert the French troops, the two officers on sentry duty suffered wounds from a hailstorm of bullets and grenades. Roberts found himself incapacitated by a grenade, and Johnson's rifle jammed. However, rather than surrendering, Johnson ripped out his knife and engaged in hand to hand combat, tearing through soldiers until he single-handedly routed the raiders. This is the battle depicted in the 1918 E. G. Renesch poster "Our Colored Heroes," which is featured in the new Penn Museum exhibit Black Bodies in Propaganda.

This new exhibit presents 33 posters that journey through decades of military history from the 1800's colonization of Africa, to the Chinese government's support for the African independence movements of the 1960s. Tukufu Zuberi, who is the Lasry Family Professor of Race Relations, Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and host of the PBS show "The History Detectives," is the curator and collector of the posters. In fact, those featured in the exhibit are part of a personal, growing collection, containing 48 in total. While Zuberi had already been interested in collecting posters, he said it was his first poster, titled as "Film Poster for Our Colored Fighters," which provided direction. "That poster began to define for me the contours of the collection," said Zuberi. "And the collection is defined by posters like that, which have been put together as propaganda themed at using the black body as a metaphor to either praise, vilify, or recruit African and African Americans into military service."

This first poster from 1918 was for a film that Woodrow Wilson commissioned to urge young African American men to join the war effort. "In order to win the war, you needed African Americans to be on the side of the military effort…" said Zuberi. "And you needed them to fight. You needed them to basically put their lives on the line." At the center, the poster shows an African American man in uniform, and he is surrounded by illustrations glorifying the life of a black soldier, such as enemy troupes raising white flags, "welcome home" parades, and medals of honor. However, as we are now able to look back on the treatment of many African American soldiers, as well as the segregation and Jim Crow laws that extended for generations, history paints a much darker picture.

"These posters often do two things," said Zuberi. "The first is a view of those very courageous individuals who fought for freedom, democracy, and equality, even though they didn't have it at home. On the other hand, it shows how others would manipulate the images of people who are second-class citizens." The exhibit contains several features that help provide a greater context for the posters, such as timelines and interactive stations. At one station, patrons can observe clips of relevant films from different periods. One of the clips is a recruitment video directed toward African Americans using footage of the aforementioned 369th Infantry, also known as the "Harlem Hell Fighters." A narrator shares the details of the victory as video images of their celebratory welcome parade and honorary statues flash across the screen. The narrator never mentions how the Harlem Hell Fighters fought beside the French, because the U.S. did not allow black men to fight beside white soldiers at the time. He could not predict how the summer of 1919 would be known as the "Red Summer" for the violent riots and hangings of African Americans, including returning veterans. Also, despite Henry Johnson's victory being used in such recruitment films, the U.S. would not fully recognize his heroism until 2003, when the Distinguished Service Cross was presented to his son, Herman A. Johnson.

In studying these posters, revealing such twisted realities, one cannot help but reflect on the nature of propaganda itself. Zuberi even said that he now looks at propaganda differently. "The potential thing with these posters is the connection between the image, the use of the image, and our motivation," said Zuberi. "The image in itself is neither bad nor good but what does that image signify?" He said that by using the black body in a positive or negative way both reinforces a certain signification but also consolidates support in a specific direction. Seeing these posters side by side, it is evident that whether it is the brave and determined soldier or the animalistic soldier with a cold sneer, the intended result is persuasion.

There is another unique issue that comes into play within this exhibit. In observing a poster titled "African Woman Executes African Man," printed in 1890, one is struck by the powerful imagery. Below a warm sky of red, white, yellow and blue, with chaos erupting in the background, a female Dahomey soldier looms over a cowering man, gripping a rifle in one hand and raising a bloodied knife in the other. It is visually stunning, even beautiful, and the vision of this woman stays long after the visit.

However, one learns through another interactive feature—a touch screen display contributing additional information on specific posters—that this particular image was designed for a French children's game with a twofold purpose. By depicting the Africans as violent and disorganized, it provided the assurance of victory. It also allowed the vicious abuse and forced labor inflicted by colonization to be masked by the dream of the "great chain of being." Essentially, it was the colonial soldiers' duty to civilize and educate the "barbarians."

There is a sense of dissonance in finding oneself in admiration of a beautiful image with a message so ugly. It is a problematical part of our history, but Zuberi maintains a positive viewpoint on this topic. He said that as long as we let go of the stupidity of the past, we can pay attention to such images and learn from them. "We don't have to run from them. As long as we understand what we're dealing with, there's only benefits from it," said Zuberi. "Knowledge enhances our understanding and rewards our research by preparing us for tomorrow. So, those who take this exhibit seriously and go to it with an open and positive mind, they will learn."

"The take home message here is the way we think about race changes over time. There's nothing permanent about it," said Zuberi. Altogether, Black Bodies in Propaganda offers an elaborate glance into history, and the nature of communication within these different time periods in a way that is concise and easily absorbed. One might be sickened by the facts and images or inspired by our ability reflect back after years of change. "This exhibit will train better your eye—your mind's eye," said Zuberi. "So, some things will become amusing to you. And at the same time they may be disgusting. But they will help you appreciate how imagery is used."