20 years later, but just as odd

When I was told a few months ago that the artist collective TODT was preparing for a show at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, I'm not sure whether I was more surprised to learn that the collective was still together or that it was coming to Philadelphia. TODT left a wake, as a friend of mine used to say about a certain storied editor.

When I was told a few months ago that the artist collective TODT was preparing for a show at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, I'm not sure whether I was more surprised to learn that the collective was still together or that it was coming to Philadelphia. TODT left a wake, as a friend of mine used to say about a certain storied editor.

TODT's early New York exhibitions were composed of some of the most intense, uncompromising art one could see in 1980s Manhattan. The three- and sometimes four-person team was as rigorously anonymous as the Guerrilla Girls, and even, possibly, as authentically uninterested in commercial success, despite a run of shows at a 57th Street gallery.

TODT also cultivated a mystique that seemed to explain its dark, obsessive mind-set. Every art-world follower knew that TODT's name not only referred to the German and archaic Dutch word for death, but also to Hitler's director of public works, Fritz Todt.

Not much has changed, except that TODT has now arrived at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery and the year is 2007 (it turns out, by the way, that the team has been exhibiting steadily, if less frequently, and its members are now living in Philadelphia and Upstate New York). TODT's art is still jaw-droppingly weird, like a fanatic's late-night experiments in the garage.

A toddler at the gallery was amused by what she could see of one of TODT's milder pieces, which involved fake grass and cute plants with small Styrofoam balls attached to them. Very young children, I realized, would see only the attractive, familiar aspects of TODT's art - the side of it that the grown-ups see last. For example, instead of just seeing a benign drawing of a large cow, horse or sheep, as the small child does, adults see the complex Frankensteinian mechanical devices attached to each animal (or running through them).

This show is really a survey - it has as many works from the 1980s and 1990s as it does recent ones - which makes it possible to see TODT's trajectory in a way that museum surveys usually illustrate. I saw, in hindsight, that TODT could have influenced any number of artists over the last two decades, most obviously Ashley Bickerton and Damien Hirst, though TODT is far more cerebral. TODT was clearly among the first to depict a world controlled by science and government. The future is a persistent theme, especially one in which fiddling with animal, human and plant evolution is routine.

Some works here are so gratuitously repellent they're funny. Laps (1996) is a real toilet with brown fluid and a pair of Speedo goggles in it that spins around madly every five minutes or so while emitting a loud, continuous flushing noise. In Rake (2001), a metal rake's teeth are embedded in dirt and crawling with dozens of enormous worms. (Worms and larvae populate several recent works.)

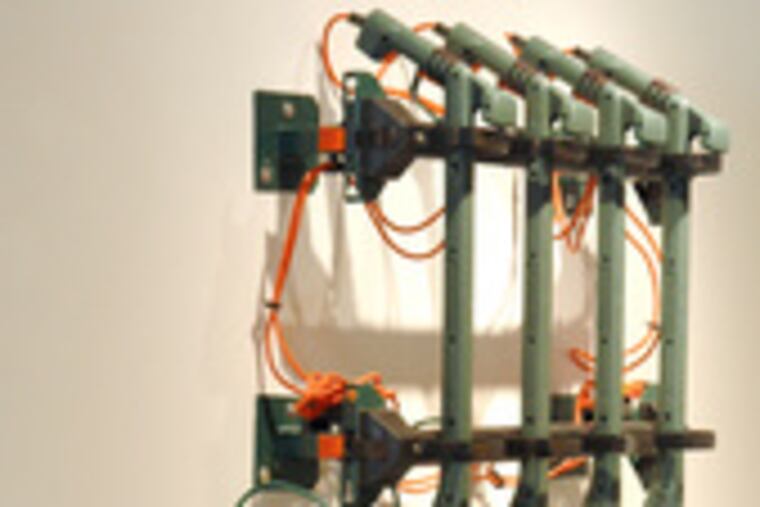

Interestingly, TODT's less obvious, less narrative-implying pieces get their philosophy across more expediently. Phalanx (1997), comprising several brand-new weed whacker-type machines affixed to a wall unit that has an electrical cord dangling from it (when plugged in, I was told, the noise effectively empties the gallery), is an incredibly slick and sinister comment on consumer culture, the bad-seed descendant of Duchamp's readymade.

Dark circles

Since his last one-person show at Larry Becker Contemporary Art in 2003, Quentin Morris, the Philadelphia painter who works exclusively in black, has been working exclusively on circular pieces of canvas and paper.

Morris' transcendent works aren't truly monochromatic, though, any more than Robert Ryman's paintings can be said to be entirely white. On canvas, Morris' black gesso and acrylic medium paintings are full of nuances, as are his drawings in graphite and Nero crayon.

The paintings, which dominate this show and are all 72 inches in diameter except for one diptych, Untitled (October 2005), have dramatically different surfaces. Some are matte, others are glossy, and the paint appears to have been applied with a variety of brushes and tools. Pinned to the wall, they give the impression of having the weightiness of leather hides; at the same time, they also suggest solar eclipses.

Morris' drawings, particularly the velvety one in Nero crayon, are reminiscent of porthole views of a black sky, but the graphite-rendered ones also bring to mind metal disks and vinyl records.

Some artists switch styles compulsively. Morris has found infinity in black.