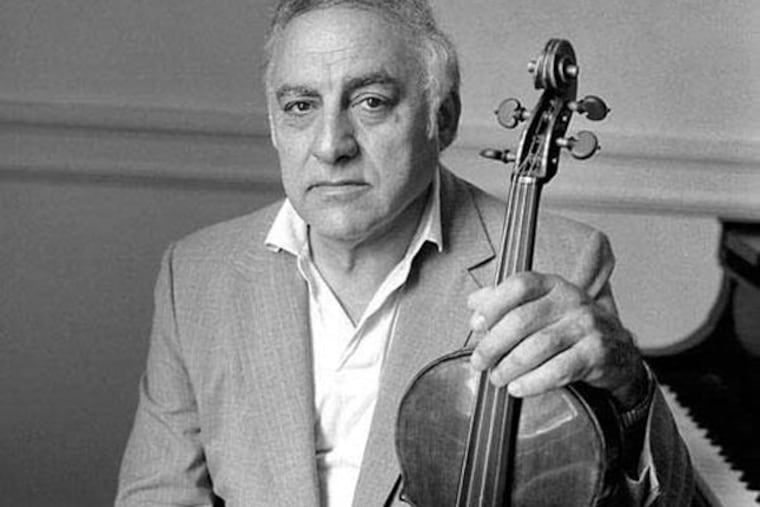

Noted violist Joseph de Pasquale dies at 95

He was born in South Philadelphia, married Franco-Russian royalty, and reigned for five decades as one of the great violists of the 20th century. Joseph de Pasquale, 95, died Monday, June 22.

He was born in South Philadelphia, married Franco-Russian royalty, and reigned for five decades as one of the great violists of the 20th century. Joseph de Pasquale, 95, died Monday, June 22.

Mr. de Pasquale, of Merion, was principal violist of two of America's golden-age ensembles - the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1947 to 1964, and then, sitting alongside three of his brothers, the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1964 until retirement in 1996.

He is credited with raising the standard of viola playing so dramatically that it remade the instrument's image, said Curtis Institute of Music president Roberto Díaz, a one-time de Pasquale protégé.

"It was the attitude about what is possible on the viola - it had to be as good as it was on the fiddle, and his playing showed it," said Díaz. "You hear some of those recordings with the Boston Symphony or Philadelphia Orchestra, and there's nothing like it anywhere to this day. It was the gold standard for what a principal violist could be, and it was an incredible inspiration for a lot of us."

The inspiration lives on, through his many years teaching at the Peabody Institute, Indiana University, New England Conservatory, Tanglewood Institute, and, from 1964 until his death, Curtis. Members of the Boston, Cleveland, New York, Pittsburgh, Minnesota and Los Angeles orchestras studied with him, as did two-thirds of the Philadelphia Orchestra's viola section.

He augmented his orchestral life as a member of one of the Philadelphia Orchestra's few standing string quartets - the de Pasquale String Quartet, a lively force on the local chamber music scene that sometimes commandeered Philadelphia Orchestra guest artists like Yo-Yo Ma, André Watts, Emanuel Ax, and Garrick Ohlsson.

The quartet comprised brothers Joseph, violinists William and Robert, and, until his death in 1972, Francis. Francis joined the orchestra's cello section in 1943, and the rest were brought to Philadelphia by Eugene Ormandy to complete the matched set.

Their father, a Germantown cabinetmaker named Oreste, determined that his boys would become successful string players, and started Joseph on violin. "My father told me after a while that he couldn't teach me any more," so he continued his studies with Philadelphia Orchestra violinist Lucius Cole, Mr. de Pasquale said in 1996. He auditioned for Curtis and was accepted as a violinist, but its string faculty, including viola teacher Max Aronoff, thought he should switch to viola.

"They said I had the long arms and big stretch in my left hand. Max said, if I would study with him, he would guarantee I would be principal in a major orchestra," he said.

So it was. After attending Curtis from 1938 to 1942, he joined Leopold Stokowski's All-American Youth Orchestra, and then the Marine Band and the ABC Orchestra in New York. In Boston, he was auditioned by music director Serge Koussevitzky, who sent for some Handel sheet music and gave Mr. de Pasquale an hour to learn the piece. "Later, he called me downstairs. There he was in his big cape, and he said, 'You are the new solo violist of the Boston Symphony,'" he recalled.

Boston was a huge success professionally as well as personally. Walter Piston wrote his Viola Concerto for him, and Mr. de Pasquale gave the first Boston performances of concertos by Walton and Milhaud. Of a 1958 Lenox performance of the Piston Concerto, the New York Times wrote: "The composer had every reason to be pleased. Mr. de Pasquale, for whom he wrote the concerto, played with such musicianly finish and, especially in the slow movement, with such ingratiating tenderness and warmth that one could hardly fail to respond to what may be one of Mr. Piston's most beautiful and moving inspirations."

Also in Boston, he met a striking blonde named Maria - a descendant of both Napoleon's first wife, Josephine, and Czar Nicholas I of Russia. She had come to the United States to be personal secretary to Koussevitzky, her uncle, and renounced her title of duchess in 1949 to become a citizen and wed Mr. de Pasquale. She died in 2005.

In pedagogy, Mr. de Pasquale was an important link to William Primrose, with whom he studied at Curtis. He instructed his students, as Primrose did, that in order to increase the smooth bow change at the frog - the end of the bow that is held in the hand - the left shoulder should be brought forward slightly, bringing the viola to meet the bow at the frog.

"This makes for a seamless connection," wrote Stephen Wyrczynski, a former de Pasquale student and chairman of Indiana University's string department, in a 90th-birthday tribute. "He also introduces the Franco-Belgian concept of 'tirez and poussez,' the pull and push of the bow over the string. One should never press or force the sound. One creates better overtones and volume by drawing the sound out, not squeezing it down."

To this day, Philadelphia Orchestra parts are marked with Mr. de Pasquale's fingerings, "which were designed to create a dynamism in the [orchestra's] middle voice," wrote Wyrczynski. "He was not afraid to suggest risk-taking. For instance, there are passages in the slow movement of Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra where the violas play the melody entirely on the C string in order to create musical tension in the sound. It had never been done before in Philadelphia."

Specific techniques like these established Mr. de Pasquale's legacies as one of the rightful, if lesser known, authors of the vaunted Philadelphia Sound.

Mr. de Pasquale is survived by children Maria Alexandra, Elizabeth Ann Giordano, and Charles N.; 10 grandchildren; and two brothers. Another son, Joseph S., died earlier.

A memorial is planned for the fall.

215-854-5611