Drexel exhibit toasts Howard Pyle, father of American illustration

The man known as the father of American illustration made his mark at Drexel. With his students, including the notorious Red Rose Girls, he created the Golden Age of American illustration.

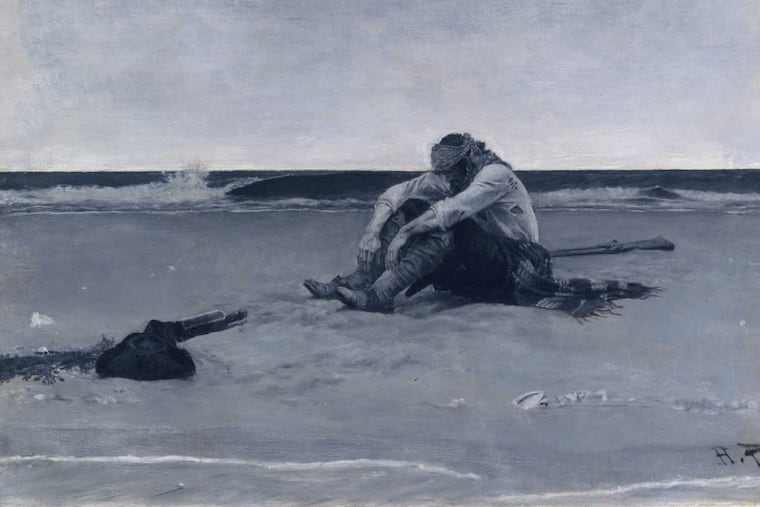

Was there a pirate Howard Pyle didn't like? A knight? A damsel?

The acknowledged father of American illustration loved them all and painted them with gusto. He showed them near death on desert islands. He portrayed them swooning when lovers were unmasked as British spies. He depicted their armored bravery, their sorrows, their sheer human drama.

All of this is clear in "Howard Pyle, His Students and the Golden Age of American Illustration," an exhibition on view at Drexel's Paul Peck Alumni Center until June 18.

Here is not only a generous selection of Pyle's own paintings, but those of his students, a Who's Who of American illustrative art — Violet Oakley, Elizabeth Shippen Green, and Jessie Willcox Smith, whom Pyle nicknamed the Red Rose Girls (more on them in a moment), as well as Frank E. Schoonover, Maxfield Parrish, and many others.

About 200 students studied with Pyle at Drexel.

"Throw your heart into the picture," he'd tell them, "and jump in after it."

Pyle taught at the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry, founded in 1891, from 1894 to 1900, and he was a critical component of the young school's foray into the arts.

But those art roots have not always been emphasized at Drexel, and Pyle's importance to the institution — his department was the first devoted to illustration in the country — has sometimes been lost in the fog of the past.

In fact, the current exhibition came about, in part, to acknowledge the role this illustrious former teacher played in the making of the institution.

Paula Marantz Cohen, dean of Drexel's Pennoni Honors College, was at a Delaware antiques show a few years ago when she ran into John Schoonover, grandson of the well-known illustrator Frank E. Schoonover.

They fell into conversation, and Schoonover told her about his artist grandfather, who studied with Pyle at Drexel and revered him.

Cohen says she had a vague sense of Howard Pyle but had no idea about the effect he had on his students and on the course of American art.

Pyle was a beloved teacher with a profound impact, Cohen says, noting that the arts and humanities are flourishing at Drexel now to a degree that recalls the old days.

Pyle, who died in 1911, left Drexel in 1900 to found the Howard Pyle School of Illustration Art in Wilmington, where he launched the career of N.C. Wyeth, among many others, whose work is also included in the show.

"Pyle was particularly supportive of his female students," said Danielle Rice, program director of the museum leadership program at Drexel's Westphal College of Media Arts and Design. "He mentored and supported them in the same way he supported his male students."

Clearly that was the case with the Red Rose Girls — Oakley, Green, and Smith — who scandalously rented the entire Red Rose Inn in Villanova and lived there together. The ménage à trois was actually a ménage à quatre, but the fourth of the Red Roses, Henrietta Cozens, joined the collective as housekeeper and gardener, not illustrator.

Oakley, Green, and Smith vowed to live together for life as partners, which led some on the Main Line to deem the Red Rose scene inappropriate.

Pyle loved it. And they loved him.

"Illustration is the highest type of pictorial art," Oakley wrote later. "Among those pictorial artists who have been definitely connected with making clear statements, preeminently stands Howard Pyle. No one, we believe, made messages more clear; nor do I feel, more beautiful, more mystical, more lofty in purpose."

All of the Red Rose Girls are represented in the Drexel show — as well as in the extraordinary exhibition of American watercolors now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

That is no accident. Illustrators — and women in general — were very comfortable using watercolor as a medium. Philadelphia, thanks largely to the presence of the Curtis Publishing Co. and its stable of hugely popular magazines, like the Saturday Evening Post and Ladies Home Journal, became a place where women could enter the professional world and make a decent living.

Smith did every color cover of Good Housekeeping magazine for 15 years. Green provided illustrations to Harper's magazine and many others. Oakley did illustrations but then became absorbed by stained glass and murals.

"Oh, my god, talk about sexy," said Kathleen Foster, curator of American art at the Art Museum who put together the watercolor exhibition. "Three women artists, none of them married, all of them pursuing high-speed careers without husbands. Talk about the newspaper feature articles. They were the darlings of the press because it was so exotic. These women were making a go of it without having any children, without being married. A new generation of illustrators and mural artists."

Pyle made that possible.

"His great theory was, as he called it, mental projection, and he based all of his criticism on that," Frank Schoonover told an interviewer in 1966. "By mental projection, he meant to throw yourself into the picture and to eliminate any preconceived ideas of technique, classical rendition or art school technique, but to paint as you felt."

Paint like a pirate.

"Howard Pyle, His Students and the Golden Age of American Illustration," through June 18, Paul Peck Alumni Center, 3142 Market St. Admission: free. Information: 215-895-2586 or drexel.edu/pennoni/news-events/pyle-exhibition.