Ann Mah’s ‘Lost Vintage’: Entry in the genre of the worthwhile summer novel

Ann Mah's book "The Lost Vintage" is a pleasant summer read — and a little bit more. It's part of a recent genre of books designed for summer reading yet also worthwhile in their own rights. We can have fun reading romances, thrillers, and mysteries — but we don't have to be utterly dumb about it. Mah's book tackles issues of history, family legacy, war, greed, and racism, while taking us on a delightful trip to the vineyards of Burgundy, speaking a lot of French, eating some great food, and stumbling upon some profound and surprising twists and turns.

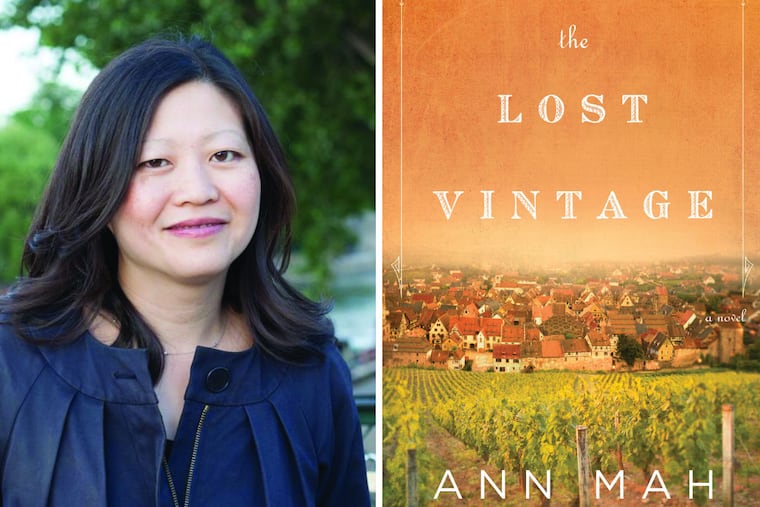

The Lost Vintage

By Ann Mah

William Morrow. 384 pp. $26.99.

Reviewed by John Timpane

This book swings between the San Francisco Bay area and the Burgundy wine-growing region of France. As we go, we drink lots of wine, get on the outside of some outstanding food, speak a lot of French — and delve into profound dilemmas involving family history, war, racism, and the value of tradition.

Pleasant, beguiling, The Lost Vintage joins a burgeoning genre of books ideal for summer reading yet also worthwhile. The list grows and grows: Tangerine by Christine Mangan, The Bookshop of Yesterdays by Amy Myerson, River of Stars by Vanessa Hua, and more. We can have fun reading romances, thrillers, and mysteries — but these books can have something to say, as well.

There's a summery lightness about this Vintage, charged with the romance of travel and food. As well it might be: Mah is a bicontinental food and travel writer, and she maintains an amused viewpoint about cultural misunderstandings. Our central figure, Kate Elliott, is an American sommelier whose family still runs a winery in ancestral Burgundy. Her mom has turned her back on the place and is a high- and oft-flying exec in Asia. Kate is studying for her final attempt at the master of wine test when a call comes, summoning her back to France.

You know she's going. We want her to go. She goes. Soon, she's earning a good backache as a vigneron, helping to bring in the harvest.

Growing richer and tastier with time, old wine, old love, and old secrets await our Kate among the vines. In this era of assured, adroit, superwomanly female protagonists, Kate is awkward, unsure, always a couple of steps behind. She's also the key to it all. She and her (often funny) cousin-in-law Heather (married to Kate's cousin Nico) clear out a junk-crammed basement in the great house, where, come on, you guessed it, a big mystery lies. Kate's bond with Heather is one of the novel's best things, going from guarded ("I was afraid she'd be too curious about my life in San Francisco, that she'd ask too many awkward questions") (which Heather does, by the way) to loving, sharing a dark family secret. Not unlike The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah or Sarah's Key by Tatiana de Rosnay, the secret involves the Second World War, anti-Semitism, and collaboration.

Kate and Heather, for different reasons, personally shoulder the responsibilities, familial, moral, and social, that such knowledge imposes. When the past changes, the present can change, too: the way we see those with whom we live, the way we see ourselves: "I found myself scrutinizing my thoughts," Kate tells us, "wary that I would discover some ingrained bias, some inherent prejudice, some evidence that I was genetically predisposed to moral weakness." From that sentence forward, we read on, and not just to see how the story turns out. We care more about Kate and her family. They are fuller, more alive to us.

Vintage also features the light, laissez-faire editing of the summer book. It's a goodhearted world. Most folks are easily likable, even more easily unlikable. (Example: We are prompted to dislike Louise, Kate's rival in love, immediately, in the snarky thumbnail "small foxy features.") We must indulge the cliches that populate these pages ("Sunday in France, I thought, was forever an idyll"), some repeatedly (prickling backs of necks, jaws dropping open, etc.). We must forgive the occasional whopper, as when Kate, visiting a monastery, wonders how to behave "amid this atmosphere of rigid aestheticism." Great to know the monks care that much about art, but what Kate and Mah mean is asceticism.

But let that pass. We take away much of value, especially in the parallel life that unfolds as the novel proceeds. And we've been smiling a lot. And eating and drinking — vicariously, but very well, indeed. "Everything you need for a balanced meal," as Nico says. (Heather adds: "And no cooking!") It's good for summer, and it leaves both heart and mind satisfied.