Anselm Kiefer says Auguste Rodin was a creative destroyer, just like him. Their joint show is now at the Barnes.

Anselm Kiefer talked with us about his creative process - and what he has in common with sculptor Auguste Rodin. The esteemed German contemporary artist is in Philly for the opening of the Barnes Foundation "Kiefer Rodin" show combining the two masters' works.

"He likes to fiddle," said Thom Collins, head of the Barnes Foundation. "We were in here yesterday, moving cases around. I was moving cases. I'm serious."

The renowned contemporary artist Anselm Kiefer acknowledged that his work is never really finished, even when it's finished. He will look at it and become dissatisfied to the extent that he will sometimes pour fiery hot lead on the surface.

Collins didn't have to contend with that. But he had a glimpse into a truth about Kiefer, whose work is a part of an exhibition opening Friday at the Barnes: In destruction comes creation.

Read Thomas Hine's review of the exhibition, which he says is both thrilling and stimulating.

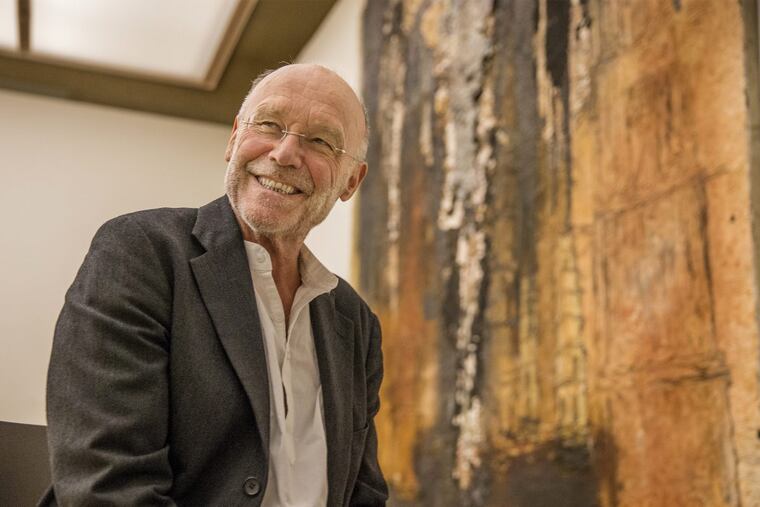

"I am an iconoclast," Kiefer said, sitting on a small chair in the Barnes special-exhibition galleries beneath one of his monumental renderings inspired by Auguste Rodin, Auguste Rodin: The Cathedrals of France. The looming 12½-foot-high canvas displays shadowy towers – towers built by Kiefer in his studio, not drawn from medieval France – with a sheet of poured lead down the center, seeming to hold the canvas together like the spine of a great prehistoric ichthyosaur.

"When I have a painting and I'm not satisfied, mostly I'm not satisfied, then I do something with it," Kiefer said. "I destroy it. I burn it or I put it outside in the snow. Or I pour lead on it, liquid lead, you know. It burns and glues at the same time. And partly I can reroll it and it takes part of the color [up] with it. I like this because it destroys the work. Good artists are iconoclasts."

Kiefer, who just received the J. Paul Getty Medal for contributions to the arts, along with Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, is in Philadelphia for the opening of an unusual special exhibition at the Barnes. "Kiefer Rodin," which has traveled from Paris, is co-curated by Sylvie Patry, consulting curator for the Barnes and chief curator at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

The genesis for the exhibition, which runs here through March 12, comes from the Musée Rodin in Paris and its director, Catherine Chevillot.

In 2013, Chevillot was looking for a graphic artist to work on a commemorative republication of Rodin's only book, Cathedrals of France, first published in 1914. She considered many artists, but no one seemed quite right. After a trip, she returned to Paris and was told that, in her absence, Kiefer had asked to spend a couple of days rummaging around the museum storage rooms, looking at Rodin casts.

"I thought, Kiefer, of course!" she said.

After considerable discussion, Kiefer's total approach to a project kicked in. He wanted to visit all the cathedrals Rodin visited. He did drawings. He had plans.

Chevillot finally said, "This is too big for a book; this is an exhibition."

The result is now at the Barnes, a 100-work exhibition that contains many works by Rodin never seen in this country, notably watercolors and plaster-cast fragments – testimony to the French sculptor's restless habit of cannibalizing works, an arm here, a finger there, a foot, a hand, a torso.

The exhibition makes the connection between the two artists clear, even though they are separated by a century, and Kiefer is, of course, German, well known for his contemplation of the moral failures of German history.

This is particularly true of his reputation in Philadelphia, where Kiefer had his breakthrough museum exhibition in 1988 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

That exhibition, which was put together by the Art Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, thrust Kiefer's epic struggles with recent German history directly in front of viewers in the form of enormous canvases slathered with mud, lead, and paint, and built up with dirt and straw.

Those familiar with the 1988 exhibition will find four monumental canvases inspired by Rodin's exploration of French architecture in "Kiefer Rodin" that echo that style from the 1980s. But the Barnes exhibit also contains a number of enormous books filled with Kiefer's surprisingly delicate and sexually charged watercolors, counterpoints to Rodin's watercolors, here for the first time.

And Kiefer has created a number of vitrines, glass display cases in which he has deployed wizened brown plants, desiccated leaves, thick depths of dirt, sheets of poured lead, metallic double helixes, and casts made from Rodin's sculptural fragments.

"I have a connection with Rodin since I was 14 years old," Kiefer, now 72, said. "You know Rilke, no? He wrote the book about Rodin."

That book, first published by poet Rainer Maria Rilke in 1903, fascinated the young Kiefer.

"This was my first contact," he said. "You know the German and French culture were always very connected. The French adored the Germans, and the Germans adored French culture."

Looking out over the Barnes gallery with its fragments seemingly shored against the ruins, Kiefer felt quite at home.

"Rodin, he destroyed his work," Kiefer said. "He cut it and put it on another sculpture. He worked by changing all things. He combined parts of different sculptures. He was a collagist, as I am, too."

Many would argue that art-making embodies the most important human effort to hold off destruction, to ward off chaos.

Kiefer says, "Art, poetry, music is for me the only real thing, all others are useless. You are an illusion. This building is an illusion. Only the concentrated work of an artist is for me real."

It is here that the paradox of the artist destroying his own work becomes most complex. It is not destruction that Kiefer necessarily aims for. Rather, he seeks a more potent art, which is why nothing can ever be "finished."

"It's never finished," he said. "Never. Never. Never. Sometimes I have to sell something, and then it's finished, you know. I need to continue. But for me, nothing is finished. I have old paintings from the '60s in my containers. I have a lot of containers, you know. And sometimes I go through and I think, 'Oh! This tells me something.' And I continue."

Kiefer Rodin

Through March 12 at the Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

Hours: Wednesday-Monday 11 a.m-5p.m.

Admission: Adults $30; seniors (65+) $28; youth 13-18 and college students with ID, $5; children 12 and under, free.

Information: 215-278-7000 or www.barnesfoundation.org