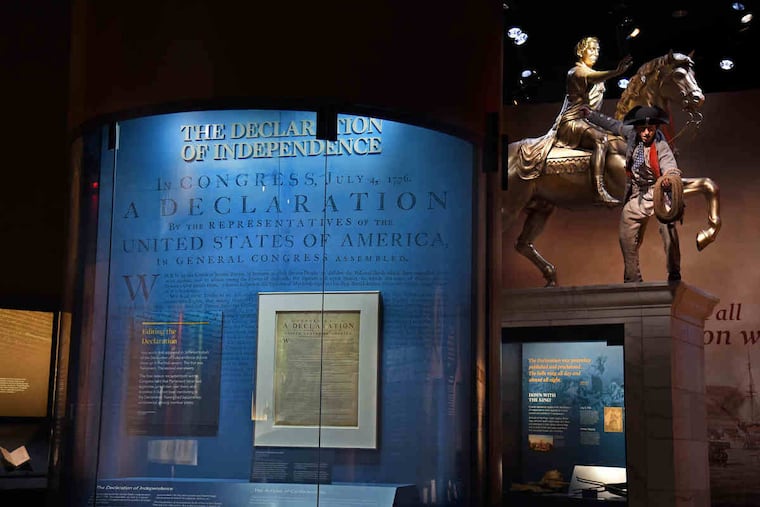

Rare version of the Declaration of Independence on display at the Museum of the American Revolution just in time for July 4th

Unique, oversize version of the Declaration is the only one known to be printed on parchment by congressional printer John Dunlap.

It's not every day, or even every decade, that the opportunity arises to see what is possibly the rarest early printing of the Declaration of Independence.

Beyond that, no one alive has ever seen this particular treasure outside the confines of the august American Philosophical Society on South Fifth Street.

Yet beginning Tuesday, when the Museum of the American Revolution opens its doors, visitors will be able to see a sight as rare as a perched California condor eyeing the museum at Third and Chestnut Streets.

The unusual Declaration — an oversize version on parchment executed by renowned printer John Dunlap in July 1776 — will be on display into November, museum officials said.

"As far as we can tell, this [Declaration] has never left our campus," said Patrick Spero, director of the society's library. "This is really unique. It is the only known version of this extant."

>> READ MORE: What to see in Philadelphia's museums this summer

The document was acquired in 1828, when the society received a portion of the papers of astronomer, society member, and ardent revolutionary David Rittenhouse.

Though it has never lent this Declaration before, the society has decided to shed its reticence and give voice to the treasures it houses. Plus, said, Spero, "It's the neighborly thing to do."

"We really do want to share it," he said, adding that the hope is that this will be the first of a series of loans between the two institutions.

On Monday afternoon, a few days shy of the 242nd anniversary of Dunlap's printing, the wrapped and boxed Declaration of Independence was loaded onto a truck, protected by a security guard, and escorted two blocks to the museum. There, it was unloaded and installed late Monday afternoon, ready to greet visitors first thing Tuesday.

R. Scott Stephenson, museum vice president of collections, exhibitions and programs, said it was an honor to display the Declaration.

"It is humbling to stand in the presence of such an authentic witness to our nation's birth," Stephenson said.

>> READ MORE: Spreading the news of independence

But what exactly is this declaration? And why and when was it printed?

Dunlap was a young printer who was tasked by Congress to produce the first public versions of the just-approved text. He labored through the night of July 4, 1776, setting the type, and eventually ran off about 200 copies on paper.

Those copies, known as the Dunlap Broadside, were dispatched across the Colonies and to Gen. G. Washington, then leading the Continental Army.

The general, in New York City, had the declaration read to his troops on July 9, who then proceeded to destroy a statue of King George III standing on Bowling Green in lower Manhattan.

There are 26 known copies of this famous Dunlap printing known to still exist. APS has one, Independence National Historical Park has one, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania has a substantial fragment. (APS also has a draft of the declaration written out by primary author Thomas Jefferson July 1, 1776.)

>> READ MORE: Phila. copies of the Declaration of Independence imbued with meaning

Only the Philosophical Society has a copy of Dunlap's singular oversize Declaration, the sole version that Dunlap printed on parchment or vellum.

No one knows precisely when Dunlap produced it or why. No knows why it is so large or why it is printed on parchment. The only certainty is that it was issued after Congress endorsed the declaration on July 4.

"We don't have an answer." said Spero.

But the Declaration of Independence invites speculation, accruing apocryphal stories like a ship attracts barnacles.

Spero's favorite theory — and he emphasizes there are no facts to back this up, only feelings — is that this oversize, sturdier parchment Declaration was printed shortly after Dunlap finished printing the paper broadsides.

The reason? To withstand the difficult, jostling circumstances of reading the document in public.

Spero likes to imagine merchant and revolutionary John Nixon standing in State House yard, on the steps behind what is now Independence Hall, reading from Dunlap's parchment broadside as the city's bells tolled and citizens gathered round on the afternoon of July 8, 1776.

It would be the first public reading of this momentous document.

"That's my wildest fantasy," Spero said, somewhat sadly. Independence Park holds that particular publicly read copy of the Declaration, presented to the park in 1951 by Nixon's heirs. The mystery of Dunlap Parchment Broadside remains to be solved.

>> SEE MORE: Photos of the Declaration's Move down Chestnut Street