Fine exhibit of fakes at Winterthur has it all: money, obsession, hubris, deception

The unusual exhibition brings together real phony paintings, wine, silver, and other objects to explore cases of forgery and the whole question of what makes a fake a fake.

A special exhibition recently installed at Winterthur Museum and Library captures the contemporary zeitgeist probably better than any other exhibition in recent memory.

It's a show of fakes.

Here is a Rothko that isn't a Rothko, a Coco Chanel suit that isn't a Chanel, a Babe Ruth baseball glove that the Babe never set eyes on, and let's not forget all the silver by Alt-Paul Revere.

You name it, and Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes probably doesn't have it, but it might have something that might be. In the immortal words of master forger Elmyr de Hory: "If my work hangs in a museum long enough, it becomes real."

The show was put together by Linda Eaton, Winterthur's director of collections and senior curator of textiles, and Colette Loll, founder and director of Art Fraud Insights LLC, a Washington consultancy. It runs through Jan. 7.

The show does not simply ask is it Ella or is it Memorex? The show speaks to a larger world of money and obsession and hubris and deception. It shows the fake and the real, the disputed real, the fake fake, the puzzlers, the possibles.

"It's not all black and white," said Eaton, the curator.

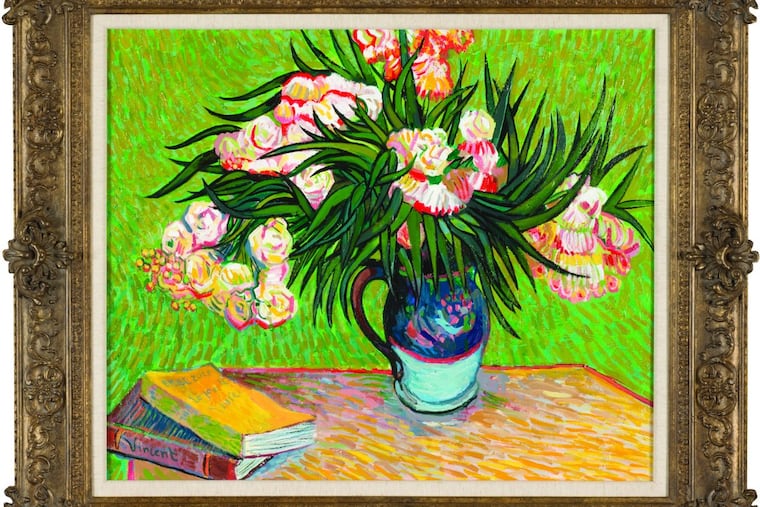

"In prison, they called me Picasso," said British artist John Myatt, painter of what he called "genuine fakes" much in demand among collectors. Myatt's copy of Van Gogh's Oleanders is part of the show. He is not Picasso.

Entering the Winterthur galleries, the first sight is a shimmering canvas apparently by Mark Rothko, bands of glowing orangey red and black.

But this is no Rothko.

It is a canvas that was purportedly owned by a mysterious – and later discovered to be nonexistent – collector dubbed "Mr. X." The real artist was Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese immigrant painter living in Queens. He provided Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales with at least 31 paintings over more than a decade by "Rothko," "Pollock," "Motherwell," and other giants of abstract expressionism.

New York's once-prominent Knoedler Gallery sold 24 of these paintings to clients who, when the $60 million fraud was revealed and Knoedler closed in 2011, were not amused.

Nevertheless, Eaton, the curator, is tickled that it opens the show.

"We are thrilled to start the exhibition with a fake Rothko," she says. "It was part of the Knoedler Gallery scandal, a huge scandal that closed down a very important gallery."

Eaton points out that no one received serious jail time "for the largest art fraud scandal in American history."

"The other important thing in the Knoedler case, I think, is the lack of transparency in the art market," she said. "Where are things coming from? These came from 'Mr. X,' who wanted to remain anonymous."

But what about due diligence? Didn't Knoedler have an obligation to check out the authenticity? Knoedler claimed it was duped, Eaton said, adding that "people say they should have known."

A case closer to home involved the selling of phony folk art paintings by Robert Lawrence Trotter, a Kennett Square painter — also represented in the show — who became frustrated by lack of interest in his own work. In the 1980s, as folk art prices began to skyrocket, Trotter decided to ride the tiger.

He sold around 50 paintings purporting sometimes to be by well-known folk artists; Trotter's works were gobbled up by collectors.

He was caught in an FBI sting and eventually spent 10 months in jail for fraud. But numerous collectors didn't want to give up their paintings – they were too good. In 1990, the court allowed four of Trotter's paintings to go to the Yale Art Gallery and one to Buffalo State University for study.

Eaton is clearly fond of Trotter, who is indeed a remarkable painter. She stood in front a work that had been donated as a forgery to the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y. for teaching purposes. Though the painting, of a mother and child, was done in 1980, the surface paint appears aged and crackled, bits of paint flaking off; the bronze-colored frame is battered and seemingly ancient.

The Fenimore Museum at first agreed to lend it to Winterthur, but then started having second thoughts.

" 'Oh,' they said," Eaton recalled. " 'We're so concerned about the condition of this piece.'

"I'm thinking, 'Wait! Wait! He did that intentionally,' " she said. " 'That's the way it's supposed to be. Whatever he put on it made the paint lift off. He whacked the frame. It's in perfect condition. No. No. No.' They agreed, finally, to lend."

Clearly there is more to a fake than being a fake, a point made by the exhibition, which is divided into four sections – intent, evidence, proof, and a final "you be the judge" gallery. Trotter's intent early on was not to deceive, but when he began making and selling works purporting to be something they were not, he crossed the line.

"If you make a pastiche, a lot of people do that," said Eaton. "It is not illegal in the United States to create fakes. What is illegal is to sell it as the real thing, to defraud someone."

There are plenty of examples of that here. One of the most noteworthy is the bottle of 1787 Château Lafitte purportedly owned by Thomas Jefferson acquired from a Parisian wine merchant in the late 1780s. The bottle was deemed a fake after wine bon vivant and collector William Koch – of the well-known Koch family of billionaires – became suspicious of the purported Jefferson connection and bought several bottles.

Koch sought out experts who performed technical analysis – carbon-14 dating and low-frequency gamma ray testing. Both high-tech tests were inconclusive. What nailed the case against the wine was the incised label. A master glass engraver determined that the glass had been cut by an electric engraving tool, not by hand.

In other words, "connoisseurship" determined authenticity.

"We teach connoisseurship, and that is the close and systematic understanding of the technology of making, and fabrication, and decoration," said Eaton. "It does not mean, 'Oh, I just feel this is right.' That's not cutting the mustard in a court of law."

On the other hand, in 2006, Koch brought suit for fraud against the source of the bottles, a German collector, Hardy Rodenstock. Koch won a default judgment, but the collector refused to participate in the case. The judgment remains unpaid.

"Who would prefer a bad original to a good fake?" master forger de Hory once asked.

It helps to know the difference, is the larger point Winterthur makes – even as it exhibits a fake of a de Hory fake, a product of the burgeoning interest in the forger's work.

"Is that a double negative?" wondered Eaton. "When prices begin to skyrocket, that's when you have to pay close attention."

Treasures on Trial is on exhibit through Jan. 7, 2018, at Winterthur Museum & Library, Tickets: $20 (adult), $18 (seniors and college students), $5 (children 2-18, free for children under 2). Information: 800-448-3883 or www.winterthur.org.