‘Frederick Douglass’: A reality as awe-inspiring as the myth

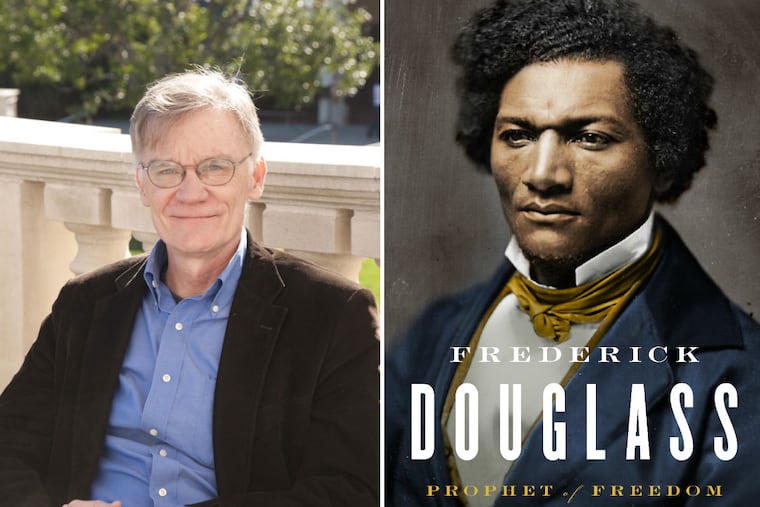

In "Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom," Yale historian David Blight writes a sweeping investigation of Douglass' life and times, also deftly integrating newly unearthed materials relating to Douglass's later life, making this the most comprehensive biography of Douglass ever written.

Frederick Douglass

Prophet of Freedom

By David W. Blight

Simon and Schuster. 912 pp. $37.50.

Reviewed by Clayton Butler

As a thinker, writer, speaker, and leader, Frederick Douglass stands second to none in the history of the United States in the 19th century. Born into slavery, at the age of 20 Douglass escaped north, and through his activism, prolific authorship, and phenomenal oratory became the most famous African American man in the country and, indeed, the world.

He is believed to be the single most photographed man of the time; only Abraham Lincoln still towers over their era in a comparable way. Lincoln, however, did not possess a first-hand experience of slavery, nor did he live to see or comment on the course the country took after the Civil War. Douglass did. His conscientious voice carried through the war, through Reconstruction, and through "Redemption" and the establishment of Jim Crow in the South. Confronted with the unfulfilled promise of Union victory, Douglass devoted most of the second half of his life to the fight against racial discrimination and the contest over national memory. To the end of his days, Douglass sought to ensure that the emancipationist legacy of the war had not been buried in the name of sectional reconciliation.

In this respect, David Blight appears the ideal scholar to write a new biography of Douglass. For his entire career, the Yale professor has researched Douglass and the 19th-century American society and culture he occupied and did so much to shape. Blight has also deftly integrated newly unearthed materials relating to Douglass' later life into his monograph, making it the most comprehensive biography of Douglass ever written. The author does an admirable job of keeping his audience culturally oriented, continually reminding the reader of the presence and crucial influence of Scripture — particularly the Old Testament — on Douglass' thinking and writing. Above all, Blight lets this remarkable voice speak for itself throughout the text. Douglass excelled at telling his own story (he wrote three autobiographies), and Blight does not talk over him.

Born in Maryland in 1818, Douglass spent time both on the plantation and in Baltimore – where he met his first wife, Anna — chafing against his enslaved condition the more he became cognizant of the alternatives of education, opportunity, and freedom. Along with Anna, he executed a daring escape to Massachusetts and quickly became involved in the antislavery community there. By the time he reached 30, Douglass had emerged at the forefront of the abolitionist movement in the United States, embarking on a demanding speaking schedule that would continue to the last day of his life, and rapidly earning a national reputation as an orator. Blight explores Douglass' relationships with people who became key to his development as a public figure, including William Lloyd Garrison. A special emphasis falls on women such as Julia Griffiths and Ottilie Assing, who became central to Douglass' intellectual and professional development.

Douglass operated an activist newspaper, the North Star, and when he grew disillusioned with the efficacy of moral suasion, collaborated briefly with John Brown, whose zeal — if not his pragmatism — he greatly admired. When the Civil War erupted, Douglass initially expressed impatience with Lincoln's vacillation on slavery but grew to respect him and became convinced of his sincerity; after the issue of the Emancipation Proclamation, Douglass actively recruited for the Union Army. Two of his sons enlisted, and Lewis Douglass participated in the assault on Fort Wagner with the 54th Massachusetts (of Glory fame).

Blight's work is no hagiography, and he takes the time to show the lesser-known, behind-the-scenes Douglass — his foibles, his family strife, his missteps, his blind spots. Yet his humanization fails to diminish his aura. The reality of Douglass is just as awe-inspiring as the myth. As an unflinching social critic and tireless advocate of African American rights, he had no contemporary equal, and his inspiration of future activists such as W.E.B. DuBois and Ida B. Wells stands as one of his greatest bequests.

As for Douglass' censure of American society for its treatment of African Americans, no one escaped, not even Lincoln. Blight begins the book with Douglass' famous 1876 speech criticizing the Great Emancipator, a speech emblematic of his career as a whole. After the collapse of Reconstruction, and the federal government's seeming abdication of its responsibility to protect the rights of emancipated former slaves, Douglass became discouraged but never despondent. For all his criticism of the United States and its leadership, he ultimately remained a patriot, simply urging his country to live up to its stated ideals. As he explained in 1846, "the best friend of a nation is he who most faithfully rebukes her for her sins — and he her worst enemy who, under the specious . . . garb of patriotism seeks to excuse, palliate or defend them." Such a message is timeless, and Blight has written a biography that will likely stand as definitive for decades to come.

Clayton Butler is a doctoral candidate at the University of Virginia. David W. Blight comes to the Free Library at 7:30 p.m. on Nov. 19.