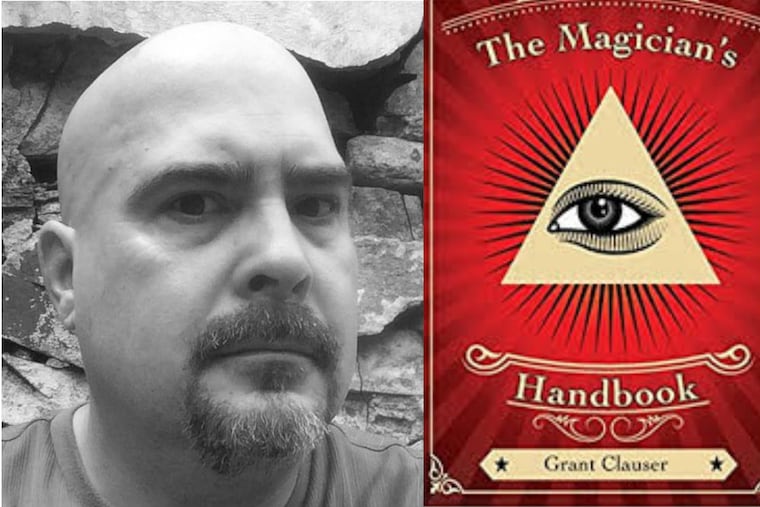

Grant Clauser’s ‘Magician’s Handbook’: A fine, magical collection from a local poet

As its title makes plain, "Magician's Handbook," Grant Clauser's latest poetry collection, boasts a unifying theme: magic, both the stage variety associated with pulling rabbits out of hats and sawing ladies in half, and the more mystical sort connected to omens, portents, and the paranormal. But every poem is also talking about the real world we all inhabit, with wit and practical wisdom.

The Magician's Handbook

By Grant Clauser

PS Books. 80 pp. $15

Reviewed by Frank Wilson

As its title makes plain, the latest collection from Hatfield poet Grant Clauser boasts a unifying theme: magic, both the stage variety associated with pulling rabbits out of hats and sawing ladies in half, and the more mystical sort connected to omens, portents, and the paranormal.

Center-stage, of course, is the magician himself. Indeed, the sequence chronicles his life, from high school to when he meets his wife to when he turns 40, then 60, to when he's on his deathbed, and much else in between. The range of thought and feeling is shrewdly bracketed by Magic in Theory and Practice, which precedes the entire collection, and the title poem, which begins Part 3: The Magus.

The former offers some advice:

It's best to believe everything

at once

while moving toward the door

with the easiest escape.

But when we get to the title poem, we learn that "It's not the lost loves / he regrets / or the lean years … but that he'd spent / so much time / hiding how it's done / that he forgot / how it ends."

Such melancholy correspondences between hiding and escape occur throughout. On turning 40, the magician worries that someday, after performing tricks for children, "an enthusiastic parent / will pat him too hard on the back / and shake loose / every dove and throwing knife, / and he'll be caught naked / like a tree in winter … " On turning 60, "He's sure someone / in the audience / is snoring … "

Punctuating this unsentimental realism are moments of genuine tenderness. A sweeter correspondence is how the title poem is prefigured in How the Magician Met His Wife:

The difference between swept away

and swept off your feet

is like knowing something's a trick

but not knowing how it's done.

This harks back to that prefatory Magic in Theory and Practice, which assures that "The real magic / is that we choose … knowing all the time / it's a trick."

This is, in short, a tightly integrated collection. The correspondences are no surprise. Alchemy, after all, was a kind of magic derived from chemistry, grounded in such axioms as "as above, so below" — that this life on earth is prefigured in the chemistry of the stars.

Nowhere is Clauser's sense of this clearer than in Darwinian: "At some point we all need / to evolve like animals, crawl / from water into air and leave / another skin behind … " The problem, though, is "skins have their own / lives, vestiges of love / and scars we try to hide … " What an insightful connection between biology and heartache.

There is little sense of the transcendent at work here, though that may be an illusion. The History of Magic Part I tells of the discovery of fire, how they "carried it from / camp to camp / scaring and bewildering the children / who grew so fond of it / they gave it new names." Then, "One day as they carried the body / of an elder out to a field / one of the children / remembered the fire … fetched it / and touched it / to the old man's body / and in that moment / invented god."

Pretty agnostic. Or maybe sleight-of-hand. After all, we are never told "The History of Magic Part 2." And toward the end, we do get Prayer:

We can't ask anymore

after the gifts of earth and water,

maybe fire, that you may cup

its heat in your palm,

send the dark back into corners.

But apparently we can ask, and we have received gifts. The magic at work here is that Clauser never invites you to think as he does, but to figure things out for yourself to your own satisfaction.

Frank Wilson is a retired Inquirer book editor. Visit his blog Books, Inq. — The Epilogue. Email him at PresterFrank@gmail.com.