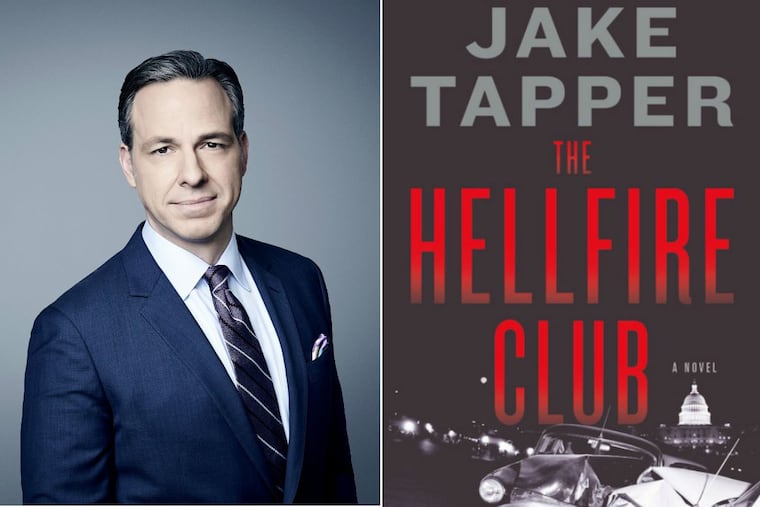

Jake Tapper's new book agrees with Donald Trump on this: 'The swamp exists'

CNN's Jake Tapper comes to Philly next week to read from his novel "The Hellfire Club," set in Washington in the 1950s. He spoke with us about the book, the nature of political power, and why no one jumps into the swamp all at once.

News flash: Jake Tapper, CNN anchor and chief Washington correspondent, has published his first novel, The Hellfire Club. It’s a thriller set during a few months in 1954 in that quiet American backwater known as Washington, D.C.

A newly minted congressman falls afoul of a shadowy network of power-brokers and interest peddlers modeled on the Hellfire Club, to which Ben Franklin once belonged.

Tapper knows how Washington works, how politics works, and how history comes back around. He brings The Hellfire Club to the Free Library at 7:30 p.m. Thursday.

A Philadelphia native, young Jake used to visit the office of Pulitzer Prize-winning Inquirer cartoonist Tony Auth, who encouraged him. As part of his Sunday State of the Nation show on CNN, Tapper has a regular "State of the Cartoonion" segment of animated political cartoons.

Tapper spoke from his CNN office in Washington about his novel, its resemblance to the present, and the lives of Washington politicians.

You're a prominent journalist and media host with an 80-hour-a-week job. So you go and write a novel?

I've been working on it for years: That's the truth. I had the concept of it for maybe a decade … I had the themes and the setting, Washington during a few months in 1954, with McCarthy and Cold War tension in the air.

It took a lot of work. Before I started writing, I consulted a lot of people, did one of those Facebook University courses with Aaron Sorkin. And there was a point, about three and half years ago, when it really started coming together in earnest. It's been a project.

Some folks will look at the themes and characters in The Hellfire Club and think of right now, starting with the themes of corruption and abuse of power. Roy Cohn, defender of Joe McCarthy and also a mentor to the young Donald Trump, is here in all his bullying glory.

The book isn't meant to be a specific comment on what's happening right now, but, sure, there are obvious tie-ins. Some of the resonance was purposeful, but most is not. I'd say there's only about a page and a half that's any different because of the Trump era.

What was true in 1954 is still true today. There's a saying that history doesn't repeat itself, but it does rhyme. Roy Cohn, obviously, was going to be in the book. And the more I researched the era, the more the themes kept coming front and center. Abuse of power was rampant. The D.C. swamp. The demagoguery.

And, most of all, ethical and moral compromise. How much are you willing to compromise your beliefs and values to achieve what you want to do, rise in your field, protect the United States of America?

Your central figure, Charlie, is a study in the hazards of compromise. He's a sympathetic character, even naïve, yet he ends up doing some questionable things.

I cover politicians all the time in Washington, and with Charlie, I wanted to explore what you see constantly here: How a person can come to Washington for all the right reasons, wanting to be a good person, and end up making deals with the devil.

Very few bad guys think they're bad guys. I'll bet you most of the people making headlines right now don't think they're the bad guys. And if we think of 1954, with this large-scale battle, as people saw it, for the soul of America, you had Joe McCarthy, or Eisenhower, or even the Communists, all fighting for the United States, for reasons they all sincerely believed in.

The same thing holds true for Charlie on a smaller scale. Charlie, like a lot of people, just wants to get in with powerful people. Nothing wrong with that, per se. But to get in with them, he does things for them, and little by little he compromises what he believes. Meanwhile, his wife, Margaret, is in shock at the man he's becoming.

What you dramatize is the gradual, all but unconscious, progression of it.

You don't leap all at once into the swamp. You take one step into it, and another and another, until you've eased all the way in. At one point, Margaret thinks to herself, "The human soul isn't sold once but rather slowly and methodically and piece by piece."

Right at the end, even Eisenhower, whom we think of as a principled man, admits to a loss of courage when he could have excoriated McCarthy in public but stopped short, afraid it would lose him the electoral vote in Wisconsin.

It's a true story. Ironically, he did not need the Wisconsin vote at the end of the day – but I think we know who needed it in 2016.

You mention Charlie's wife, Margaret, who has a steadier moral vision.

To me, she's the strongest of the good guys in the book. A woman friend told me she thinks Margaret is the hero. She doesn't flinch when she sees what's right and wrong. She does see Charlie as redeemable.

In the thrillers I admire, the best ones have strong women. That's one reason I wanted Reagan Arthur [editorial director of Little, Brown] as my editor. I learned a lot from her, and from my wife, about creating a strong, fully alive female character. I have, I hope, a few of them in the book.

The swamp, the web of conspiracy … it has always extended well beyond just "government corruption," reaching far into the private sector, into business and international power interests. Is there a sense at the end that you can't beat it, that it'll always be there?

The Hellfire Club doesn't have a naïve ending, let's put it like that. It's not as though Charlie single-handedly changes the political system. Look, that's why the book's about the swamp: The swamp exists. Trump wasn't wrong when he talked about it on the campaign trail.

When Charlie finds out that his intern, Sheryl Ann Bernstein, reads about only politics and international affairs but not business, he says: "And who do you think is telling those politicians what to do?" A tremendous amount of political energy is spent catering to business interests. Sometimes that's good, because it creates jobs. And sometimes it's bad.

An example in the book, Sam Zemurray of United Fruit, had a tremendous influence on U.S. foreign policy. And Eisenhower warned about the military-industrial complex.

Do you have another novel in the pipeline?

I have lots of ideas for other Charlie and Margaret books, taking them through different periods in recent history, one in 1962, one in the late 1960s. But let's see what happens first with this one.