Meet Ben Franklin's tragic pal who made Pa.'s paper money hack-proof

Joseph Breintnall's largely forgotten life story could fill volumes: friend of Ben, horticultural partner to John Bartram, unlikely midwife to Pennsylvania's paper money, nature lover obsessed with snakes (and ill-fated snakebite victim), and tragic figure who walked into the Delaware River one day and kept walking until he drowned.

They met in the 1720s, strivers, tradesmen, hungry for skills to improve themselves and Philadelphia. They both loved books and inspired a small group of friends to organize the Library Company of Philadelphia, the first sustainable public lending library, pooling membership dues to order books from England to share and discuss.

You know the leader: Benjamin Franklin.

"Breintnall was a scrivener and a poet, at the center of culture, in a glorious Philadelphia period," said Ken Finkel, Temple University history professor and past curator of prints and photographs at the Library Company. "But while Franklin worked pragmatically on his career, Breintnall was more of a dreamer."

In addition to books, Breintnall was crazy about plants. He roamed nearby woods, collecting leaves from trees he could not identify. "He wasn't so much a botanist," said Finkel, "as he was fascinated by the sheer beauty."

Because of his elegant penmanship and writing skills, Breintnall became secretary of the Library Company. It was his duty to order books from their London agent, Peter Collinson. Even better, Collinson was a member of the Royal Academy. Finally, someone to help identify the trees Breintnall so dearly loved. Trouble was, by the time ships crossed the ocean, leaves crumbled. Breintnall had to find a better way.

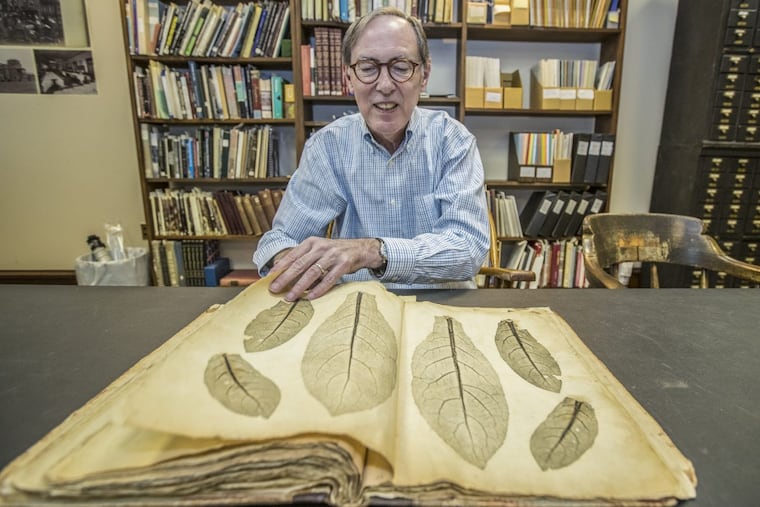

Inspired by Franklin, Breintnall slathered both sides of freshly picked leaves with thick, indelible printer's ink and sandwiched them between two sheets of paper. He made impressions using a heavy roller. It took a long time for the oil-based ink to dry, but the resulting prints — one of which is featured in "The Living Book" — were startling in their beauty and detail.

"They were far more accurate than anything produced by copperplate engraving, a technology not yet available in the colonies," said Library Company librarian Jim Green. Breintnall sent these prints to Collinson, who shared them with fellow academics and British horticulturalists. Not only did the experts identify the plants; they also bought the prints.

Breintnall introduced Bartram to Collinson. "Soon the three developed a side business, shipping American seeds and saplings to British connoisseurs, and shipping books about botany to Philadelphia," said Finkel.

"He made leaf prints for 13 years, driven not by profit nor reputation, but rather by the beauty of the material and the efficiency of the technique," Finkel said.

"I have more to show you," Green added, rolling in a cart with treasures from the Library Company collection.

"Franklin wanted to win the contract to print Pennsylvania's currency," Green said. "Counterfeiting was a serious issue. To create designs too unique to fake, he and Breintnall made plaster molds of leaves resting on fabric. They used these molds to make lead printing blocks."

Innovation won Franklin the lucrative contract. "Very few of the banknotes that Franklin printed personally still exist," Green said. "But here is currency printed with his molds."

Franklin's objective was profit. Breintnall's was the pursuit of natural science and authenticity. "He was an imaginative and disturbed man," Green said.

Consider Breintall's obsession with rattlesnakes. It wasn't his alone. Europeans were fascinated by reports about the New World, but also afraid of the wild unknown. "The American rattlesnake became a quintessential symbol — long before the bald eagle. It was both seductive and dangerous, embodying the serpent/devil who inhabited America's Garden of Eden," explained Finkel.

"Franklin capitalized on its menace in his first political cartoon, 'Join or Die,' " he said. "But Breintnall, like even educated others, believed that snakes had special powers. A snake would hypnotize and paralyze you if it caught you in its gaze."

On a collecting excursion in 1745, Breintnall heard cowbells. Looking up, he recognized the herd being driven home. Offering help, Breintnall climbed the steep trail but lost his footing. He grabbed a rock to steady himself, but instead disturbed a rattlesnake, which promptly bit his right hand.

Breintnall was terrified, certain that death was imminent. He tried to suck the poison out of his hand. His lips swelled. He turned the rock over, smashed the snake's head, grabbed its carcass and ran to town, sucking and spitting out the poison along the way.

Friends offered therapeutic advice: They burned the snake; put a bird poultice on the wound; applied turmeric, vinegar, and white ash bark. They made Breintnall keep his elbow bent to prevent poison from reaching his arm. For nine days he suffered pain, swelling, and high fevers. He survived but never really recovered.

He wrote a detailed letter to Collinson describing the episode and effects. Already depressed, he worried about his unsteady hand and failing eyesight.

Less than a year later, out in the woods, he approached the Delaware River. He got to the water's edge, removed his clothes, and kept walking. Not long after, his lifeless body washed up on the New Jersey side of the river.

His widow, Esther Parker, donated two volumes of leaf prints made by her husband to the Library Company. In gratitude for Breintnall's dedicated service, the Library Company voted her a gift of 15 pounds and, for their son, free lifetime use of the books.

The Living Book

On display through Jan. 5, 2018, at the Library Company, 1314 Locust St. The exhibition includes scrap books, pocket diaries, family bibles, public ledgers, puzzle books, and instructional guides (to birth control, penmanship and anatomy).

Hours: 9 a.m.-4:45 p.m. Monday to Friday.

Admission: Free.

Information: 215-546-3181 or librarycompany.org.