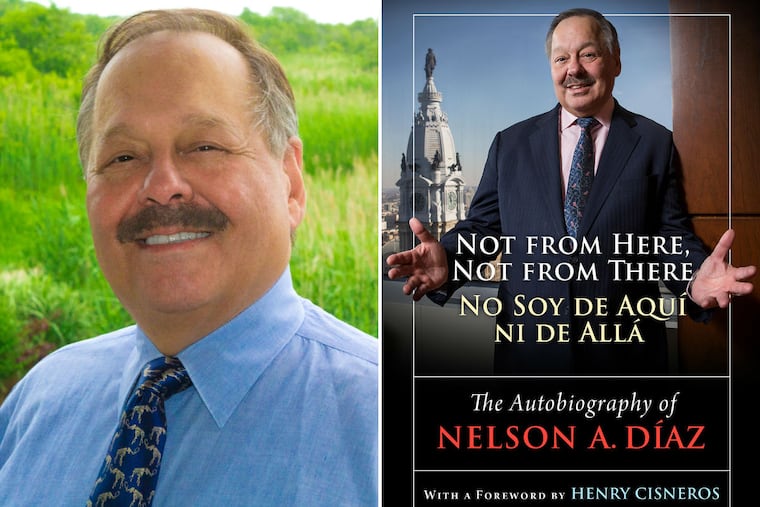

Nelson Díaz on a lifetime of being ‘the first Latino’

Pennsylvania's first Latino judge talks about his new autobiography, "Not from Here or From There/No Soy de Aquí ni de Allá," which he's bringing to the Free Library on Oct. 9.

Starting from elsewhere, new Americans make their own ways. Often, their lives are an odyssey from first to first to first.

Such has been the life of Nelson Díaz, lawyer, judge, activist.

He came to the United States from Puerto Rico in the womb of his mother and was born in Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan in 1947. He grew up in West Harlem. "I was a vulnerable child, left alone in a building overstuffed with people living in squalor," he writes in his new autobiography, Not from Here, Not from There/ No Soy de Aquí Ni de Alla: The Autobiography of Nelson Díaz. He tells of overcrowding, sexual abuse, violence, drugs, and gangs.

Wait, you might say, this is the same Nelson Díaz? Temple Law School's first Puerto Rican graduate? At 34, Philly's youngest and first Latino judge? City solicitor? General counsel for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in the Clinton Administration? That Nelson Díaz?

True to his book's title, Díaz stresses the doubleness of being Puerto Rican American. "As a Latino," he writes, "I am several things at once. Being not any one thing makes identity a difficult thing to hold onto. … I am a stranger in my own country and a citizen of an island where I have never lived. I have never been truly at home or accepted in either place."

He brings his book to the Free Library at 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, Oct. 9, in conversation with writer Sabrina Vourvoulias. He has written his life story, he says, "to motivate the community in the art of striving."

One moment you're a teenager in a Harlem gang. Just a few years later, you're going to college. Something must have happened to you around 15. What was it?

I was not proficient in English. I had street English, but Spanish was what we spoke at home. I was a class clown, unruly, and I got bad grades.

But when I was 15, my mom took me to her church, a little storefront church of maybe 200 people. The congregation was mostly teens and young adults. A lot of young people there had been through Teen Challenge, Dave Wilkerson's program for youths who had been in gangs.

I go to this church and see a number of my former gang mates there. That gave me pause. I was treated so well, so welcoming, that I went through a total change. Faith was part of it, too: I started to believe that because I was God-made, there was nothing I couldn't do.

I started to hide from my gang mates, stay in my room, and memorize the books for my exams. I entered our building the back way to avoid my gang mates. So I started getting better grades, going from D's to A's in a year.

I wasn't getting it all, of course, but I began to think maybe I could be an accountant, help get my family and myself out of Harlem. I was very afraid I'd get caught up in drugs. I saw friends dying on the streets in Harlem. I had to do whatever I could to get out. Until I finished college, I essentially kept myself in my room or the library.

In 1969, you graduated second in your class from St. John's University in New York with a degree in accounting, and you had an accounting job ready and waiting for you. This is when, as you put it, Peter J. Liacouras "bamboozled" you into coming to the Temple Law School.

I had started, but not finished, a program meant to get more minorities into law schools. And Peter found out and started campaigning. He had a vision of bringing more minorities in.

He called me almost every day: "Oh, you'll love Temple, we have so many Puerto Ricans here," and so on. When I got there, I was truly awakened, let's just put it that way. No Puerto Rican had ever graduated from the law school or passed the bar. Only four African Americans had passed the bar in the previous eight years.

That's where your career in activism began.

I started studying with my then-classmate Carl Singley, and we began to organize the Black Law Student Organization. Our last year there, the BLSO took over the law school because the dean refused to allow us to come see him about problems in getting minority students to succeed.

We resigned from the school and picketed. As a result, the dean resigned, and we were given a role in recruiting 10 Latino students and 25 black students. In 1972, the Pennsylvania bar became a multistate bar, and I passed, the first Puerto Rican to pass. It was more luck than talent.

Thus began your long association with Philadelphia. The town's relationship with its Puerto Rican community has been odd, quite different from other towns such as New York or Miami.

That's partly due to the city itself, and partly to who the Puerto Ricans were who first came here. Many were agrarian-based people who wanted to be back there but had to live here, where they were never comfortable.

On both sides of the relationship, there's a colonial mind-set, and it takes generations on both sides to work our way out of it. Voting rates are very low — you don't see Puerto Ricans interested in the vote until maybe the fourth generation.

Looking over the work you've done in so many public realms — judicial reform, energy, diversity in the police department, bilingual government services — I'm struck especially by your continued interest in housing.

I tried to improve the quality of life for people who live in public housing. Housing is a human right. And at HUD, right down to today, I've fought against high-rise housing, which doesn't work anywhere else in the country except for maybe New York.

In 1994, I issued an opinion that allowed public agencies to partner with private developers in public housing redevelopment projects. It's still known as the "Díaz opinion." I'm particularly proud of that.

Hey, I've lost more than I've won. I love the city and the opportunities I've had to make life better for people. Even if I get knocked on the head sometimes.

You call your mother a towering influence in your life. Did she enjoy seeing you become a judge?

Yes, she was pretty happy. On the other hand, she was not happy at all about me running for mayor in 2015. She looked at politicians as thieves, so she was happy that I lost: "I don't want to be part of a society of thieves."

She died very content. You can see how much she did in my life — besides chasing me with a bat through Harlem to get me to go to school.