Sarah Weinman’s ‘The Real Lolita’: A girl is kidnapped in Camden, and a great novel is written

In the gripping and heart-rending "The Real Lolita," Weinman paints a vivid picture of the notorious Sally Horner case and a wholly empathetic portrait of young Sally Horner. Weinman also connects the Horner case to Vladimir Nabokov's provocative 1955 modernist novel, "Lolita." Sally Horner of Camden may have been the "real" Lolita, or at least an important shaping influence.

The Real Lolita

The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel that Scandalized the World

By Sarah Weinman

HarperCollins. 306 pp. $27.99

Reviewed by Chris Patsilelis

March 1948. Cute, bright Florence Sally Horner, 11, walked into a Woolworth's in Camden and, on a dare, filched a five-cent notebook.

Before she could exit the store, however, a hawk-faced man grabbed her arm and said, "I am an FBI agent. And you are under arrest." He then let her go. In June, the same man abducted Sally and forced her to endure a 21-month odyssey from New Jersey to Texas to California with repeated sexual abuse.

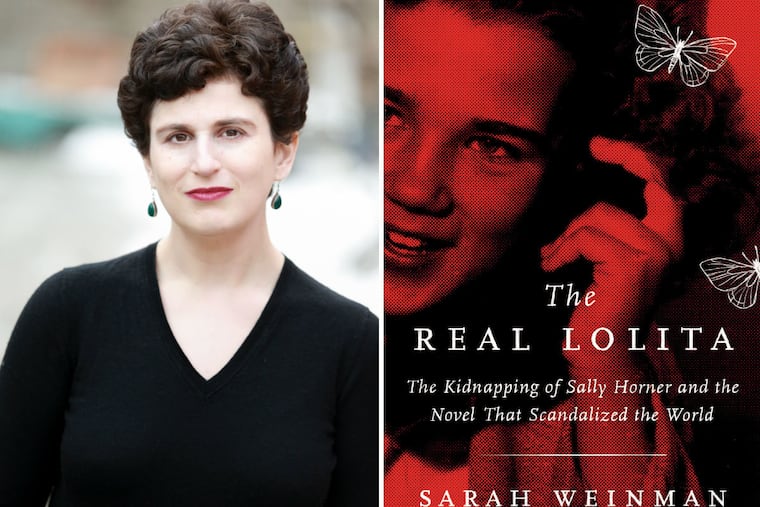

In the gripping and heartrending The Real Lolita, Sarah Weinman, author of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Sisters (2013) and Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s & 50s (2015), paints a vivid picture of the notorious Sally Horner case and a wholly empathetic portrait of young Sally Horner. Weinman also connects the Horner case to Vladimir Nabokov's provocative 1955 modernist novel, Lolita. It's not just that Nabokov knew about the Horner case as he was struggling with the novel: He followed the case closely as it unfolded. Sally Horner of Camden may have been the "real" Lolita, or at least an important shaping influence.

That phony FBI agent, in reality one Frank La Salle, garage mechanic and convicted rapist, told Sally that, unless she went away with him to Atlantic City, she would be sent to a horror-filled reformatory because of her notebook theft. She was to tell her mother she was going to the Jersey Shore with friends. He would call Sally's mom, identify himself as the father of one of Sally's friends, and verify the story. Incredibly, Ella, Sally's mother, bought it. She did not discover the true situation for weeks. And Sally, Weinman tells us, continued to believe the threat of reform school if she tried to escape. On Aug. 5, 1948, an eight-state police search began.

The book switches between the story of Sally and that of Nabokov, who in 1948 was teaching literature at Wellesley College in Cambridge, Mass., when not traveling across America indulging in his passion of collecting butterflies. He was also having great difficulty with a novel he had been working on for at least five years. At first titled The Kingdom by the Sea, it later was renamed Lolita. Nabokov's novel, Weinman reminds us, explores the mad sexual obsession of middle-aged professor Humbert Humbert for the teenage nymphet Dolores Haze, or "Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul," as Nabokov's hyperventilating professor describes her. Using overt Horner references from Lolita and Nabokov's own index cards on Horner, Weinman shows that the novelist "seeded" the Horner kidnapping story throughout Lolita.

But don't fiction writers frequently use real-life incidents in their stories? Yes, but Weinman points to what she calls "willful obfuscation": the apparent reluctance of Nabokov and his wife, Véra, ever to acknowledge Sally Horner's story as an underpinning of one of the world's most controversial classics. Weinman contends that Nabokov did this because he didn't want the real Horner story somehow to take precedence in readers' minds over his self-vaunted creative genius.

Back to the real Sally's predicament: Still in the clutches of sexually abusive Frank La Salle, Sally traveled all across America, much as do Humbert Humbert and Lolita in Nabokov's novel. Using prudent speculation to fill in blank spots in the story, Weinman shows us how they lived as father and daughter in New Jersey, Maryland, Texas, and California. Eventually, an adult neighbor at a Dallas trailer park, Ruth Janisch, discovered the secret and called Sally's mother. Sally was soon rescued and reconciled with her family in March 1950. La Salle went to prison and died there in 1966. He appears to have been a man driven throughout his life by obsession and delusion: Even in his later appeals, he insisted he was somehow Sally's father.

Sally did not long survive her liberation. She died in a car crash in Cape May County on Aug. 18, 1952, during something like a first date. On the last page of this book is a photograph of a vibrant, attractive Sally Horner, age 15, summer of 1952. Much more than a true-crime story, Sarah Weinman's The Real Lolita beautifully restores a real human being to the real world.

Chris Patsilelis lives and writes in Meriden, Conn.