Terrance Hayes’ ‘American Sonnets’: History talking in his voice

Terrance Hayes' "American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins" is the work of a poet of this moment, haunted as much by the present as by the past, as much by the light of the American promise as by the blackness of his own skin. These are sonnets, all right — but no poet in any other time, could have written them quite this way.

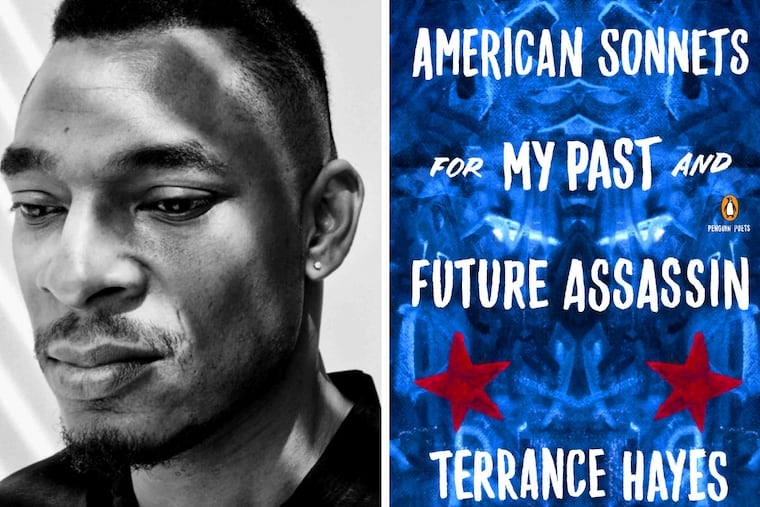

American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin

By Terrance Hayes

Penguin. 112 pp. $18

Reviewed by John Timpane

These are sonnets, all right — but no poet in any other age could have written them like this.

Much-recognized Terrance Hayes gives us American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins. These 70 poems concern much of what drives our present moment: the Trump culture clashes; debates over race, gender, and identity; the haunting presence, in every step of American life, of the past, including war, bigotry, Jim Crow, and the sense of endangerment that is an inextricable part of living while black in America. "America's struggle with itself," one poem tells us, "Has always had people like me at the heart of it."

True to the poet's art, that me may stand for black men like the poet named Terrance Hayes, and it may also stand for every me shoved to the outskirts.

Stringent but flexible, strong but not strained, Hayes' poems are crammed with passages that resound long after reading. Here's one: "After blackness was invented / People started seeing ghosts." So brilliant, reminding us that "blackness" is a social institution, a convention, something we invented. It's not seven primarily a skin color; it's a method of seeing and treating and erasing people. Another sonnet gets seemingly stuck on the word life, but read its last three lines aloud, and hear the rising alarm, the struggle against, the struggle toward:

I live a life

That burns a hole through life, that leaves a scar for life,

That makes me weep for another life. Define life.

Life means something different each time round: personal existence, abstract existence, duration, way of living, and, finally, undefined (undefinable?) term. That challenge, to the reader, to anyone, stops the poem, and the reader, dead.

Like the poems, like the book, the speaker of the lines feels himself forever yoked to his assassin, the same one who has killed him in the past and will kill him in the future. Who or what is this assassin? Above all, in this book, the assassin is a condition of life.

Ta-Nehisi Coates has written that U.S. culture is a conspiracy against the body of the black man. Some say blacks are crazy to be this paranoid, to feel this endangered. But there's a sentence that floats throughout Hayes' sonnets, again and again, like the return of the irrepressible: "But there never was a black hysteria." There's only the "I" of these poems, the assassin, and what binds them inescapably. "Assassin, you & me: we believe / We want what's best for humanity."

Hayes writes. " … Do you ask, why should you die for me if I will not die for you? I do." (Do what? Die for "you"? Or ask the same question?) Elsewhere, we read: "Like no / Culture before us, we relate the way the descendants / Of the raped relate to the descendants of their rapists." The sick, broken race relation in this country is not a feature of capitalism or patriarchy: It is the culture.

Hayes' poems keep returning to the Trump election. In one place, the chief executive is called "Mr. Trumpet." Sometimes Hayes lets the identity of his addressee stay implicit, although loudly so:

Are you not the color of this country's current threat

Advisory? And of the pompoms at a school whose mascot

Is the clementine? Color of the quartered cantaloupe

Beside the tiers of easily bruised bananas cowering

In towers of yellow skin? …

You are the color of a sucker punch,

The mix of flag blood & surprise blurring the eyes, a flare

Of confusion, a contusion before it swells & darkens.

Swelling, darkening, this collection, however, is not confined to the political. The sonnet "You know how when the light you spatter spreads" is one of several beautiful poems of love and desire. There is also reminiscence, pictures from (someone's) boyhood and family.

An explosion of poetry is being published right now in something of the same tone, aimed at something like the same topics and topicality, reaching for an aggrieved self-justification. Much is being published because of what it says and who is writing it. American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin is better than that. It is art, accomplished art, in and of itself, giving us a singular, cherishable voice that commands music, history, and language. Its worth, yes, does involve what it says to us, or makes us think about, this moment in this place, yet beyond that, it does what good poetry does. It slips all nooses and stands on its own merits.