Homeless addicts' fragile lives

A look at a disenfranchised urban population is part descriptive, part policy analysis.

By Philippe Bourgois

and Jeffrey Schonberg

University of California Press.

392 pp. $24.95 (paperback)

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Elijah Anderson

Nowhere have the hard economic times been as hard as in the nation's cities.

As American jobs are routinely exported to countries where labor is cheaper, poor people in the United States find themselves competing with the poor of developing countries. At the same time, the United States has experienced high rates of immigration from all over the world. The result is a low-wage job market that is increasingly competitive, creating persistent economic dislocation for urban populations. Great numbers of people are not adjusting effectively to deindustrialization, particularly in the context of the current recession.

With legitimate enterprise languishing, the underground economy, particularly drug dealing, often picks up the slack. Enterprising drug cartels are always on the lookout for new recruits. The disenfranchised urban population is their potential customer base, along with, increasingly, the middle-class suburbs.

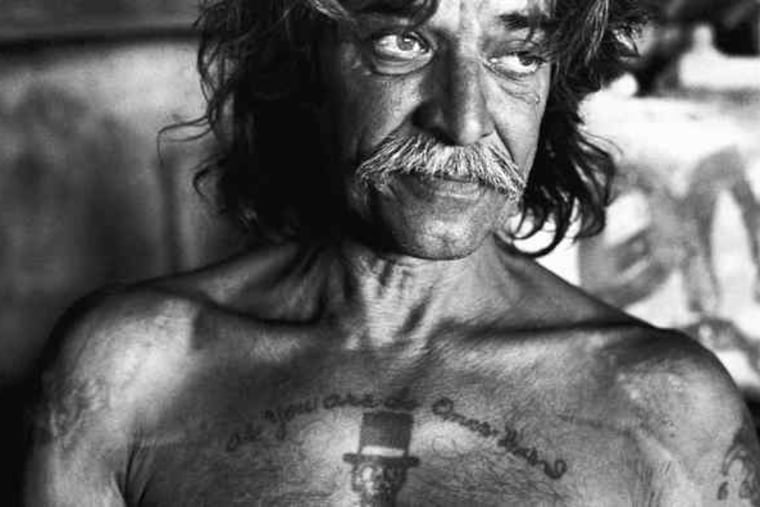

The self-described "righteous dopefiends" of the new book by Phillipe Bourgois and Jeff Schonberg are a stark embodiment of this disenfranchised urban population.

Bourgois and Schonberg describe their heroin-addicted subjects as lumpen, a term coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to refer to the lowest elements of society in France of the 1840s. Bourgois and Schonberg view their subjects as "a vulnerable population that is produced at the interstices of the modes of production." Dislocated from the economy, they are caught in the purgatorial lurch between the old economy and the new one, unable to exit the cyclical effects of poverty, violence, and drug abuse.

Their fragile existence is vividly rendered in the words and pictures of Bourgois and Schonberg, gleaned from 12 years of eye-opening ethnography in San Francisco, observing the comings and goings of homeless heroin addicts.

The dopefiends inhabit an encampment under the freeway at Edgewater Boulevard where mainstream society is literally passing them by, minute by minute, day by day, a constant reminder of their own immobility, submerged status, and lack of visibility.

Bourgois and Schonberg reveal the world of the drug addict in riveting detail, becoming active observers of the everyday lives of their subjects. The book fluidly weaves together narration, first-person accounts, dialogue, field notes, and photography for a thoroughly comprehensive depiction of the complex lives and interrelationships of the Edgewater homeless.

The reader witnesses Felix "muscle" his heroin and Sonny take a hit in his jugular vein with Hank's assistance. Readers learn Tina's personal history of sexual abuse and hear in her own words how she became involved in prostitution at 16 and learned to view sex as a goods-for-services transaction. They hear the black crack dealer on the corner disparage the white dopefiends for their filthy, odorous appearance and lack of hygiene, while those same dopefiends claim white supremacy over African Americans, choosing to move encampments when too many blacks come to inhabit their original outpost.

The addicts form communities based on a moral economy of sharing; it is considered unethical to allow another addict to be "dopesick" (suffer heroin withdrawal symptoms), and therefore sharing of needles, drugs, alcohol, and other resources is the norm. Many of the dopefiends frequent the hospital emergency room for treatment of infected abscesses, the result of skin-popping (injecting heroin into fatty tissue or muscle.) Most have hepatitis C and are at risk for HIV and a host of other illnesses resulting from their drug habit and the conditions of extreme poverty in which they reside.

Interpersonal violence and the threat of law enforcement are omnipresent in this subculture. Addicts will do whatever is necessary to ensure their next "fix," often working in the underground economy as dealers or "hitting licks" - stealing to get by. Legitimate work is difficult to obtain and even harder to retain, given their situation. Shelter, sustenance, and family become subordinated to the drug in the constant struggle to stave off dopesickness every five to six hours and thereby "stay well."

Bourgois and Schonberg explore family relations, letting the reader in on how drug addiction has affected the users' extended family relationships, examining their childhoods through personal accounts and their relationships, or lack thereof, with their own offspring. The reader is often reminded that the subjects are someone's child, father, uncle or wife.

Issues of race are salient. The authors describe an "intimate apartheid" in the camps, where despite a shared indenture to heroin and a communal condition of homelessness, whites and blacks tend to keep their distance. Drug preferences and methods of injection vary across racial lines. Black panhandlers receive less money from white donors than white panhandlers, and indigent blacks are more likely than whites to receive inferior treatment in hospitals. The book indicates with a multitude of examples that the inequality normally found in the society at large is also found in the streets.

Bourgois (professor of anthropology and family and community medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and author of the highly acclaimed In Search of Respect) and Schonberg (a photographer and a graduate student in medical anthropology at the University of California, San Francisco) are highly empathetic and competent ethnographers, and Righteous Dopefiend presents an authentic perspective on this drug-addict subculture and its root causes. The book deftly mixes description and policy analysis, so that readers can picture this world while obtaining an understanding of its structural causes and the "neoliberal" shifts in policy over the last few decades that have so exacerbated the situation of these truly disadvantaged people.

While making useful references to extant academic literature, the book is an engrossing narrative that remains focused on its main "characters" and the intimacies of their lives. The longitudinal aspect of Bourgois and Schonberg's research allows readers to follow these people over a significant segment of their journey, in and out of love, hospitals, homelessness, highs, and rehab.

The authors' investment in this collection of intimate realities becomes, in turn, the readers' investment, and it is impossible not to care, or at least be intensely curious, about the fate of each person as the narrative unfolds.

Righteous Dopefiend is quite simply one of the most original and important works of its kind and the coauthors are to be commended for their thorough and dedicated research. It is a pathbreaking photo-ethnography, powerful in presentation, content and scope. At times harrowing and graphic, the stories contained in the pages of this book also possess a remarkable poignancy.

A must-read, Righteous Dopefiend will rock the world of the sheltered middle class and shed new light on the pervasive structural inequalities plaguing contemporary society.