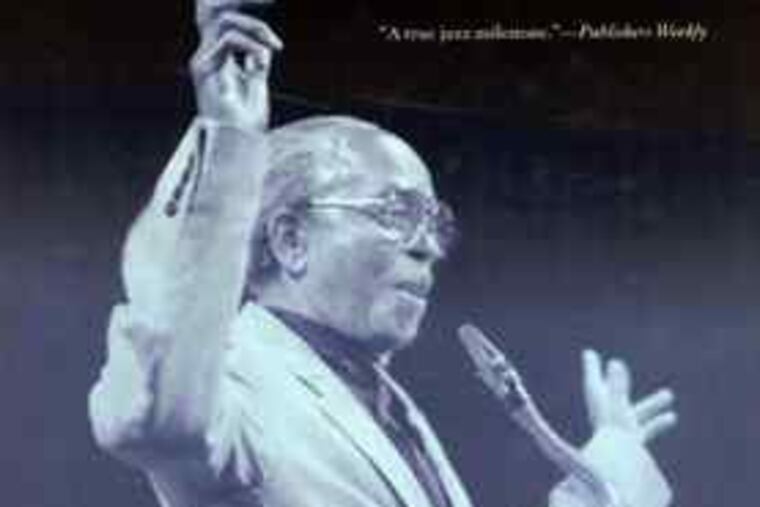

Time he blew his own horn

Even in his autobiography, Jimmy Heath, Philadelphia native and jazz virtuoso, shares the spotlight.

The Autobiography

of Jimmy Heath

By Jimmy Heath

and Joseph McLaren

Temple University Press. 344 pp. $35

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Eric Fine

From the outset, Jimmy Heath's contributions to jazz often went unacknowledged.

In the Philadelphia native's long-awaited autobiography, I Walked With Giants, Heath recalls being omitted from the credits of a Miles Davis album released in the early 1950s.

"This seems to have been a recurring theme in my career," he writes, " 'little guy passed by.' "

Heath, who turned 83 in October, went on to distinguish himself on three saxophones while appearing on dozens of albums. He composed several tunes, notably "Gingerbread Boy," "Gemini," and "C.T.A.," that became modern jazz standards, in addition to longer, socially conscious works. He will leave behind an impressive legacy.

During his youth, Heath performed alongside Davis, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Milt Jackson, Clifford Brown, Art Blakey, and Philly Joe Jones - "giants" by any standard.

Yet, even in his autobiography, Heath shares the spotlight. His account of his own life is dotted with long reminiscences from others. A typical one is pianist Ray Bryant's recollection of Philadelphia's jazz scene in the 1940s and 1950s. (The text is in italics whenever someone other than Heath is "speaking.")

It's tremendous that so many guys came out of Philadelphia who have really made huge contributions: Coltrane, Benny Golson, Lee Morgan, McCoy Tyner, and Bobby Timmons. There's something about Philadelphia that made it unique. They used to say it was the water. The atmosphere was fertile at the time and there was a rash of musicians who were actually making a livelihood. It was one of the places to be if you wanted to really develop.

Readers accustomed to literary autobiographies and memoirs will be disappointed. The writing is, at best, utilitarian. Entries like Bryant's appear throughout the book. Many originate from recorded interviews with Heath's family, colleagues, and proteges. Some offer folksy or insightful commentary; the majority read like testimonials that add little to Heath's narrative. Heath is by turns candid and colorful, although his anecdotes and reminiscences are weighed down by minutiae - names, dates, addresses, recordings, concerts - that have little bearing.

Heath and cowriter Joseph McLaren present the book chronologically in four sections. Segregation plays a crucial role in the first two sections; so does the widespread use of heroin by jazz musicians. Heath recalls a night after a Los Angeles booking in October 1950 when Coltrane nearly died from an overdose.

"He cooked up his stuff, drew it up, and shot it into his arm. He immediately fell out on the floor," Heath writes. " . . . If we hadn't revived him, he certainly would have OD'd, and the Coltrane that people know now would never have existed."

Heath overcame his own addiction after receiving a six-year sentence to Lewisburg Penitentiary, roughly 60 miles north of Harrisburg, for selling drugs. Ironically, his musical reputation grew while he was behind bars. Five of his compositions found their way onto trumpeter Chet Baker's album Playboys (1956).

Heath was paroled in May 1959 after serving 53 months. He met his wife Mona Brown shortly thereafter, and in November recorded his first album, The Thumper (Riverside Records). Riverside's producer, Orrin Keepnews, helped Heath get a cabaret card in New York, a license to perform often denied to ex-convicts.

In 1964, Heath moved to a residential cooperative in Queens, N.Y., where he still lives. He would return to Philadelphia to perform at clubs such as Pep's and the Showboat. The 1960s were a difficult time for musicians of Heath's generation because of the increasing prominence of rock and funk music.

Heath adapted. He incorporated contemporary rhythms, and the occasional use of synthesizers, after forming the Heath Brothers, a sometimes contentious collaboration with his family: bassist Percy Heath, a cofounder of the Modern Jazz Quartet who died in 2005, and drummer Albert "Tootie" Heath. The band's album Live at the Public Theater (Columbia) received a Grammy nomination in 1980.

Heath joined the faculty at Queens College in 1987, and began receiving his due in the 1990s. Heath's album Little Man Big Band (Verve) received a Grammy nomination in 1993. In addition, arts organizations and academic institutions, extending from the National Endowment for the Arts to the Juilliard School, honored Heath during public ceremonies.

Indeed, the man who walked with giants has been celebrated in his own right.

.