Another collection of essays from prolific New Yorker writer

An editor not known for diplomacy once introduced to me the fact-checker who would be working on our project, with this blunt assessment: "Just so you know, Larry can be a real pain in the ass . . . but then that's what we pay him to be."

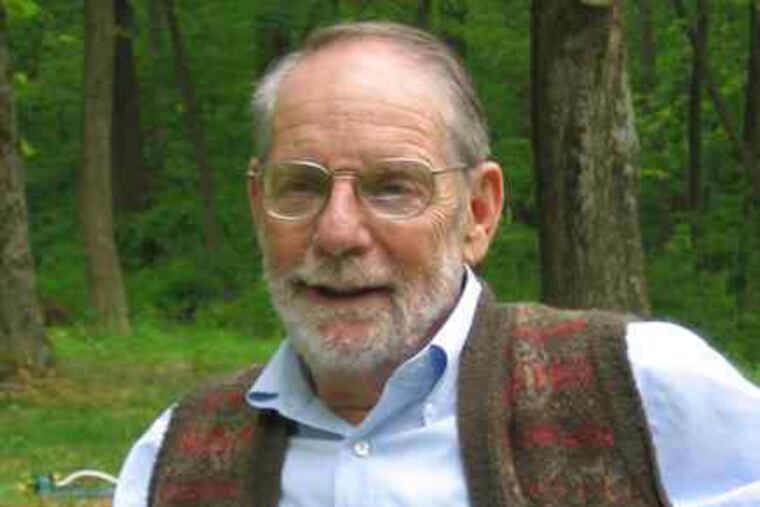

By John McPhee

Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

240 pp. $25.

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Bill Lyon

An editor not known for diplomacy once introduced to me the fact-checker who would be working on our project, with this blunt assessment: "Just so you know, Larry can be a real pain in the ass . . . but then that's what we pay him to be."

This unsparing summation is brought to mind while reading the essay "Checkpoints," one of 10 entries in the latest book by the venerated and celebrated and imposingly prolific John McPhee. It is entitled Silk Parachute, and it lands, as does almost everything written by McPhee, with an easy, elegant grace, like, well, not unlike a silk parachute.

"Checkpoints" is an homage, gently and deftly humorous, to that greatly put-upon, often misunderstood, and frequently unappreciated artisan whose daunting mission is to verify, certify, ramify, clarify . . . to prove, disprove, or otherwise spare the writer some know-it-all reader's tart taunt along the lines of "How could you not know the atomic weight, squared, of plutonium?" A good fact-checker is possessed of a single-minded tenacity and, like a Rottweiler, simply won't let go. (A pause here while the fact-checker attempts to discern whether tenacity is a trait further advanced in Rottweilers than in other breeds.)

Silk Parachute is the title of not only McPhee's book but also his tribute essay to his mother, on the occasion of her reaching 99 years. It is a mixture of memories, gently recast, softened by the years but not uncomfortably maudlin.

McPhee has a loyal legion of fans and admirers (I plead guilty), so that it is a pretty good bet they have read these words before, when they first appeared in the New Yorker, the magazine for which he has written for going on half a century. But rereading them in no way diminishes the enjoyment; think of libations with an old friend. The list of his anthologies now runs to 30 and occupies a full page. His has been a wildly successful run, with no apparent end in sight.

He continues to be drawn to esoteric subjects, with an obvious fondness for quirks and oddments, for the arcane and the technically complex. He immerses himself with a scholar's meticulousness and a journalist's curiosity. No detail is too small to be examined, reexamined and re-reexamined.

Almost always, this approach works. But occasionally you feel you have been told more than you ever really needed to know, overwhelmed by minutiae, buried in trivia. A case in point is "Spin Right and Shoot Left," McPhee's paean to lacrosse, on which he dotes. Mildly interesting. But 62 pages? S-l-o-w-w-w sledding.

Still, that's one offering, and only one, and one out of nine after all, and the other nine are varying degrees of superb, and . . . well, nine for 10 is, by any standard, worthy of raging envy.

Besides his mother, McPhee devotes a piece to his daughter and her unrelenting search for the perfect photographs, taken by a camera roughly the size of a building.

And he turns the light on two of his grandchildren (he has 10 in all, and all are named in the dedication), and they are portrayed as unbearably bright and inquisitive and just altogether perfect. (Those of us with grandchildren of our own grant him automatic dispensation for his blind spot. We understand completely what it is like to have such perfect progeny. Not only that - we would be delighted to show you pictures. Here, sit down.)

To those of us who, for far too many years, have trekked up the New Jersey Turnpike, destination Meadowlands, and thought this must be what postapocalyptic Earth will look like, McPhee presents a prideful rebuttal - take that, Tennessee - a defense of his native state layered over with his specialty, geology.

That specialty is dizzyingly put to use in "Season on the Chalk," in which he spins time travel - dinosaurs and Roman legions - and explores the chalk formations underlying parts of Europe, home to crypts and caverns where champagne is made without losing the bubbles.

There is also an intriguing aside about The Rude Man, a chalk figure 180 feet high, and his spectacular genitalia.

Golf is in Silk Parachute, too, even though the author confesses that he abandoned that infuriating game decades ago. For these purposes he is an observer, having been credentialed for the U.S. Open, a tournament in which, invariably, the competitors moan about the unfairness of the playing conditions, whining that there is a conspiracy, the intent being to embarrass them. McPhee reprises the stinging riposte of a United States Golf Association official: "We're not trying to humiliate the best players in the world; we're simply trying to identify who they are."

The essay "My Life List" is perhaps best read on an empty stomach, seeing as how it opens with a researcher who trolls the countryside in search of roadkill, which she prepares and then consumes (the weasel was excellent).

McPhee must have the digestive system of a goat, for he enumerates at length his own courageous menu over the years and around the world . . . mooseburgers, mountain oysters, assorted insects, reptiles, all manner of nuts and berries and roots, puffins and bears, and a 40-pound king salmon, frozen and transported on an inventive odyssey from the Yukon to New Jersey, and arriving as hard as granite.

McPhee's most adventurous drink has been identified as bee spit.

After all this you find something comforting about his confession that every night, just before dinner, he ingests a shot of bourbon. Clearly, here is a man after our own heart.