Malcolm X as a social radical constantly evolving

In his eulogy for Malcolm X, noted actor and activist Ossie Davis offered something to consider for those who would reduce his legacy to nothing more than fiery demagoguery, asking rhetorically: Did you ever talk to Brother Malcolm? Did you ever touch him or have him smile at you? Did you ever really listen to him?

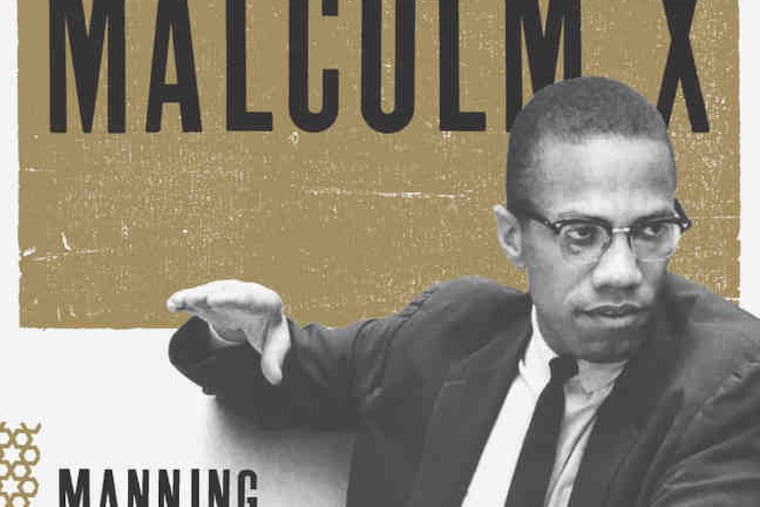

A Life of Reinvention

Viking. 608 pp. $30

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Kia Gregory

In his eulogy for Malcolm X, noted actor and activist Ossie Davis offered something to consider for those who would reduce his legacy to nothing more than fiery demagoguery, asking rhetorically:

Did you ever talk to Brother Malcolm? Did you ever touch him or have him smile at you? Did you ever really listen to him?

In the brutal and bloody racial tumult of Jim Crow, when blacks, especially black men, were denied every human dignity, Malcolm X stood for them, as Davis declared that day in 1965, as a symbol for "our manhood, our living, black manhood."

Malcolm was a towering figure, handsome, sandy-haired, spotlessly dressed, charismatic, and uncompromising in his resolve to uplift black people, and in turn America itself, in his relentless phrase, by any means necessary.

As a member of the Nation of Islam, and its most public spokesman, he preached to blacks a message of reinvention through the strictures of the Nation. He lectured on the teachings of Elijah Muhammad that black Americans were the original people of the world, the lost Asiatic tribe of Shabazz, forced into slavery, and to wander in America's racial wilderness. He unabashedly carried the message to conventions, college classrooms, Harlem street corners, television audiences, and radio programs. He branded all whites as devils, a scathing indictment of an entire race for racial discrimination. He also blasted the black middle class as nothing more than "Negro Uncle Toms," who turned away from the plight of poor and working-class blacks trapped inside America's ghettos, sinking in a swamp of job discrimination, substandard housing, and violent racism.

Malcolm's assassination in 1965 seemed to seal his reputation as a one-dimensional figure, as the late Columbia University professor Manning Marable notes in Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. His detractors accused him of being violent, racist, fascist, and anti-Semitic. Others hailed him as one of the most influential African Americans in history.

His legend was reborn decades later through the hip-hop lyrics of a new black-power generation, in the confines of America's ghettos, in post-apartheid Africa, in posters and memorabilia emblazoned with his stern likeness and caustic words, and in director Spike Lee's epic 1992 movie titled Malcolm X, much of which mirrored The Autobiography of Malcolm X, coauthored by Alex Haley.

Yet for Marable, a leading scholar on black history, many questions about Malcolm had been left unanswered and parts of his life and legacy unexplored.

Unlike Haley, whose primary source was his subject, and much of whose book was edited after Malcolm's death, Marable, who died of complications from pneumonia just days before his book's publication, used exhaustive research, including Malcolm's early speeches and letters, once-closed FBI surveillance files, and interviews with veteran Nation of Islam members, including Louis Farrakhan. The result deconstructs much of what has been popularized about Malcolm X, and offers a rich, revisionist portrait.

In nearly 600 pages, Marable lays out the life of a man in a continual process of becoming: from troubled youth to street hustler to black separatist leader to pan-Africanist with a global, multicultural vision. Along the journey, Marable uncovers some surprising, yet refreshingly human revelations: an exaggerated criminal past, a homosexual relationship with a white businessman as a youth, negotiation meetings with the Ku Klux Klan, marital infidelities, and Malcolm's plan toward the end of his life to take the crime of American racism to the United Nations. At the time of Malcolm's death, Marable shows that the fallen man was still struggling to become.

Marable begins the book with Malcolm Little, who grew up in Lansing, Mich., one of seven children of parents drunk on the self-empowerment philosophy of Marcus Garvey. Malcolm's father, Earl, a carpenter by trade, often took a young Malcolm to meetings of Garvey adherents, where Earl would lead chants of "Up, you mighty race, you can accomplish what you will."

When Malcolm was 6, his father was killed by a streetcar. The family sank into poverty, often going days without food. When Malcolm was 13, his mother, Louise, was committed to an asylum.

Malcolm bounced through a series of foster homes, later becoming Detroit Red, a smart, wanton teenager hustling for survival and identity. In prison for burglary and related crimes, he was often visited by his siblings who had converted to Islam under the Nation. He followed suit, becoming Malcolm X.

Against the backdrop of the civil rights movement, he dedicated his life to growing the Nation, which ironically would later mark him for death.

Marable vividly paints the conflict within the man as he rose in prominence and his worldview expanded. A pivotal moment came when Malcolm learned that Muhammad, upon whom he had bestowed the title "honorable," and for whom he had said he would gladly lay down his life, had extramarital affairs with NOI women, including Malcolm's ex-girlfriend. Muhammad, by then a wealthy man, refused to be financially responsible for the several children that resulted.

As civil rights groups gained momentum and won a string of victories through sit-ins and boycotts, Malcolm had to acknowledge the weight of their movement, and his desire to jump into the fray, which NOI members were forbidden to do.

And after his 1964 pilgrimage to Mecca, where he prayed and ate with white Muslims, Malcolm turned away from his antiwhite racist rhetoric. Malcolm, as Marable presents him, was never afraid to evolve.

Malcolm eventually broke with the Nation, and founded Muslim Mosque Inc., a religious group, and the Organizations of Afro-American Unity, a Harlem-based political group, under the ideology of multicultural universalism. Both groups floundered because of Malcolm's extensive travels to Africa and the Middle East, but he returned home to Harlem in late 1964 rededicated.

Despite Malcolm's many missteps, oftentimes inviting, daring controversy, Marable shows a man deeply thoughtful, a natural, magnetic leader who was also profoundly flawed. He struggled in becoming a good husband, father, and redeemer, sometimes within his own self. But in his goal to confront racism, and get black people to hold their heads high, he was an unyielding radical.