Celebrating James Joyce's 'Dubliners' at 100

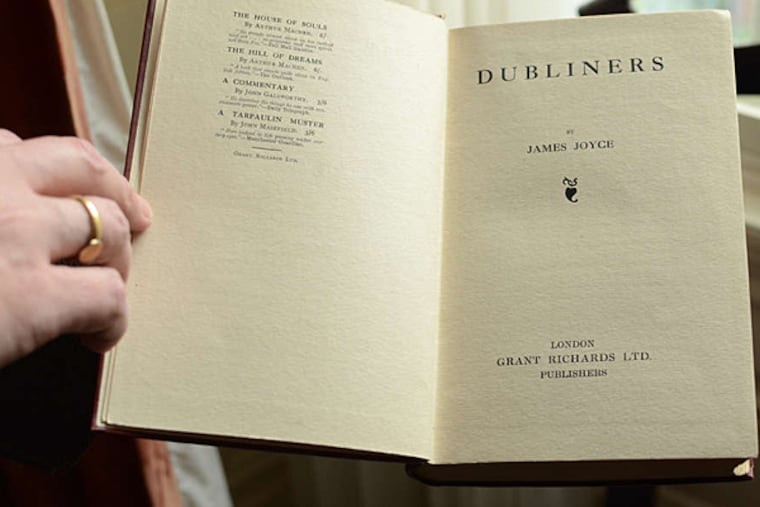

'Dubliners is one of the great books of the 20th century." Bracing words from Colum McCann, a National Book Award-winning novelist (Let the Great World Spin). Sunday is the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce's Dubliners, by the London house Grant Richards on June 15, 1914.

'Dubliners is one of the great books of the 20th century."

Bracing words from Colum McCann, a National Book Award-winning novelist (Let the Great World Spin). Sunday is the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce's Dubliners, by the London house Grant Richards on June 15, 1914.

It comes a day before Bloomsday, the day on which Joyce's Ulysses takes place.

The Rosenbach Museum and Library is in the midst of a weeklong Bloomsday celebration (bit.ly/1kxQkrP), including, on Monday, readings from Ulysses all over town. And it's having a members-only celebration of the Dubliners milestone on Tuesday.

As for Dubliners, it took a decade for Joyce to find a publisher willing to risk this collection of 15 stories, truthful depictions of people's lives in the early-20th-century city, told in what was then an unfamiliar and original style. ("Every word is aptly chosen, and placed well, almost pregnant with meaning," says Jean-Michel Rabaté, professor of English and comparative literature at the University of Pennsylvania. "Joyce said he wrote the stories with 'scrupulous meanness.' ") It begins with tales concerning children and moves through to adolescence and adulthood, culminating in the short novel "The Dead."

Joyce had come close a couple of times, but publishers balked at the subject matter and/or style of storytelling. When it finally appeared, it marked for Joyce, then 32, a major publication - and, many think, the beginning of literary modernism.

In his foreword to a new illustrated edition of Dubliners published by Penguin Classics (336 pages, $17; illustrated by Roman Muradov), McCann writes that its stories "contain some of the most beautiful sentences ever written in English." Here are two:

From "Araby": "But my body was like a harp and her words and gestures were like fingers running upon the wires."

From "The Dead," one of the most widely admired sentences in English: "His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead."

McCann writes by e-mail that "Joyce was way ahead of his time. A hundred years later there's still a timelessness about the work. Even if you haven't read Joyce, every writer is influenced by him. In many ways he is the bedrock of the contemporary literary experience. I don't think that will ever wane."

Local teachers and readers agree. Rabaté's 2001 book James Joyce and the Politics of Egoism looks at his fiction, and Rabaté also has a French translation of Joyce's play Exiles forthcoming. He thinks it's "a wonderful idea to celebrate this anniversary. If you want to read Joyce, you should begin with Dubliners." He sees Joyce in a line of great fiction writers, from Tolstoy and Maupassant on to Hemingway and other greats.

Andrew Ervin, a novelist (Extraordinary Renditions and the forthcoming Burning Down George Orwell's House) living in Manayunk, says he thinks of Dubliners "as a novel, not as a collection of stories. . . . The attention to detail in that entire collection just staggers me. . . . Just mind-blowing."

Max McKenna is a fiction writer and critic, as well as a former Penn student who is now a graduate student at the University of Chicago. He lists many ways in which Dubliners has had an impact. "The unified short-story collection, in one place and time, that was new," he says. "Whenever a writer, such as Faulkner, tries to center work in one place, you might see Joyce there. Also, in its often harsh detail, it has a modern, urban feel you've seen in a lot of fiction since."

McKenna also sees Joyce using techniques that are now in every writer's kit bag. In "The Sisters," a boy learns his longtime friend, Father James, has died. But the focus shifts away, without notice, to the priest's sisters and a chat they have about him. "It doesn't resolve," McKenna says. "It doesn't end the way we expect stories to end. But there's a unity to it, nonetheless."

What about "stream of consciousness"?

"You can certainly find it in 'Eveline,' " says Rabaté, "in which we are very much in her head."

Same goes for Duffy in "A Painful Case," or Gabriel Conroy in "The Dead." Things occur without narrative comment, cinéma verité-style. And you can find the "epiphany," in which a character comes to a realization about his life and actions. I first read "Araby" at about the age of its central figure, a romantic-headed boy who tries to impress a girl by getting her a gift from a city bazaar. When he gets there, though, he finds it's a dump. And his epiphany is unsparing: "Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger."

As years pass, the star of the show, more and more, is "The Dead." McKenna says "the story is so compelling - a man's crushing, irrational jealousy over his wife's youthful love affair with a man who is now dead." It was made into an exquisite movie in 1987 by director John Huston.

" 'The Dead' alone makes Dubliners a work worthy of its reputation," says Kevin Grauke, a fiction writer (Shadows of Men) who teaches at La Salle University. "Its final paragraph plumbs a depth of feeling that has been imitated often but very rarely approached, much less matched."

Ervin teaches a master class on the famous first sentence - "Lily, the caretaker's daughter, was literally run off her feet" - which he thinks "may very well be the greatest opening line in literary history." Lily's name has overtones of purity. "So there's a moral system put in place with the very first word." Her father's a caretaker, which suggests a social hierarchy of rich and poor. In the father and daughter we have overtones of family and gender.

"Then there's the 'literally run off her feet.' Of course, she's not literally run off her feet, otherwise she'd be on the floor, but the third-person narration comes from within her point of view, like she's thinking that she's run off her feet from working too hard. Those 10 words accomplish more than most novels. And then the story only gets better."

June 16, or Bloomsday, has become a literary holiday in many places, celebrating the day on which Joyce's novel Ulysses is set. A reading of the entire novel is traditionally staged at the Rosenbach Museum and Library here in town for Bloomsday.

McCann says, "I think Jan. 6, or Little Christmas, when 'The Dead' is set, will become a landmark literary anniversary." That would give Dubliners a rightful celebration.

RE-JOYCE-ING

Bloomsday Festival 2014

Monday: Free readings from Ulysses. Dozens of readers throughout the day, at the Free Library (1901 Vine St.), Rittenhouse Square, and the Rosenbach Museum & Library (2008-2010 Delancey Place). Information: www.rosenbach.org

Tuesday: Rosenbach Museum and Library members-only celebration of 100th anniversary of Dubliners.

Wednesday: Kevin Birmingham, "The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce's Ulysses." 7:30 p.m. at the Free Library, 1901 Vine St. Free. Information: 215-567-4341 or www.freelibrary.org.

Through Aug. 31: Exhibit, "I'll Make a Ghost of Him: Joyce Haunted by Shakespeare." Rosenbach Museum & Library, 2008-2010 Delancey Place. Information: 215-732-1600 or www.rosenbach.org.

215-854-4406 @jtimpane