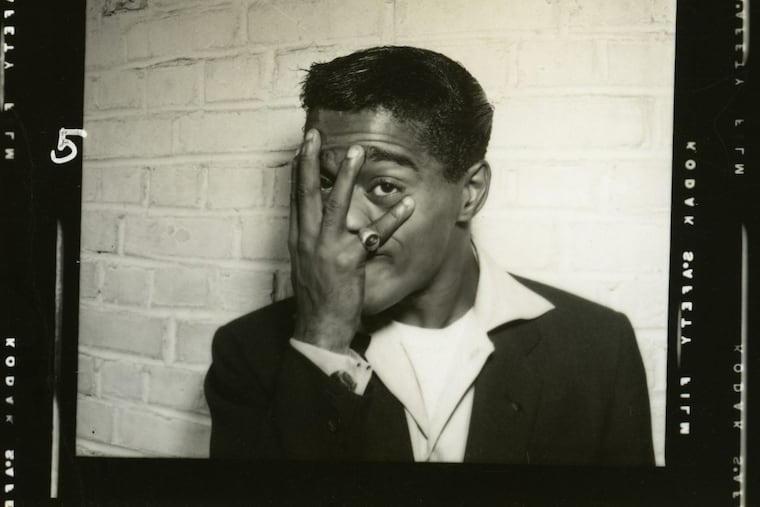

Sammy Davis Jr. was a civil rights pioneer, so why was he left behind by changing times?

Sam Pollard's documentary about the jack-of-all-trades entertainer and racial pioneer plays the Philadelphia Film Festival on Thursday and Sunday.

When Sammy Davis Jr. was serving in an integrated U.S. Army unit during World War II, the already seasoned entertainer was regularly subjected to racial abuse.

His nose was broken three times, and his fellow soldiers once painted him white to humiliate him.

Once, he recalls in an interview included in Sam Pollard's documentary Sammy Davis Jr.: I've Gotta Be Me, which screens at the Philadelphia Film Festival on Thursday and Sunday, he struck back and floored a tormentor with a punch in the face.

It was a hollow victory, however. "He got up and said, 'Well, you beat me. But you're still a n-,' " Davis remembered. "That's when I realized, even if you win, you don't win."

That cruel truth is a theme that runs through the life and career of the former child vaudevillian and lifetime people-pleaser — Davis made his movie debut at 7 as a scene-stealing hoofer in Rufus Jones for President in 1933 — who became a jack-of-all-trades star, singing, dancing, and acting in the era of civil rights struggle and social upheaval in the 1950s and 1960s.

Davis was a trailblazer. On Eddie Cantor's Colgate Comedy Hour in 1952, he helped integrate network television. With his Las Vegas pals Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin in the Rat Pack, he helped embody a notion of enlightened hip. His onstage kiss with Paula Wayne in The Golden Boy in 1964 is said to be the first-ever between back and white actors on a Broadway stage.

But success is tinged with bitterness. His appearance with Cantor — who was instrumental in Davis' conversion to Judaism after he lost an eye in a car accident — elicited racist outrage. When white guests saw him lounging poolside at the Sands in Las Vegas in the 1950s, their request that the pool be drained was agreed to by management.

The Rat Pack's integrated act sent a message of progress, but Davis was treated like a mascot, often the butt of crude jokes. In I've Gotta Be Me, which was produced for PBS's American Masters series and which takes its title from the 1968 ode to individuality that was a late career hit for Davis, Martin carries his diminutive friend across the stage during a show and says, "I'd like to thank the NAACP for this trophy."

Pollard's film includes interviews with Quincy Jones, Billy Crystal, Whoopi Goldberg, and Jerry Lewis, as well as commentators Gerald Early, Margo Jefferson, and Michael Dinwiddie. It shines light on lesser-known aspects of Davis' romance with Kim Novak, which was brought to an end by Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn, who allegedly ordered a mob hit on Davis if he didn't end the affair and marry African American singer Loray White (which he did).

After all the barriers broken and indignities suffered — and after marching with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Alabama in 1965 — Davis was left behind by the changing times, viewed as a showbiz relic from a more conservative age. He cemented that image when, seeking the influence of an insider, he campaigned for Richard Nixon in 1972, offering a hug to the chief executive that led to his being labeled an Uncle Tom.

Pollard, an Emmy- and Peabody-winning filmmaker who has directed American Masters documentaries on August Wilson, Zora Neale Hurston, and John Ford and John Wayne, and who has edited many of Spike Lee's films, tells Davis' tale with sympathy and performance clips that convey the breadth of his talent, whether as an uncanny impressionist or, most dazzlingly, a nimble tap dancer who seemed to float above the floor. Particularly moving is a 1990 TV special that includes a Michael Jackson tribute and a duet danced with Gregory Hines, recorded the same year Davis died from throat cancer.