Can ‘Nova’ showing us what brains really look like on drugs change the way we see addiction?

PBS series tries to fight stigma with science with a hard but hopeful look at addiction and how to treat it.

What we don't know — or refuse to believe — about treating opioid addiction is killing people.

That's one big takeaway from "Addiction," a hard but hopeful new hour of PBS's Nova that shows, with brain scans, not frying pans, what our brains actually look like on drugs, and that highlights some promising approaches to treating addiction.

Too few patients, though, have access to them.

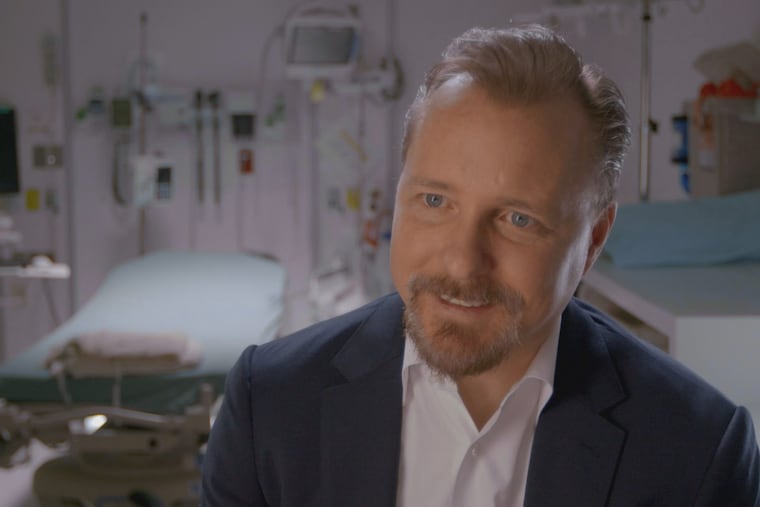

For physician Corey Waller, one of the experts weighing in on the Wednesday, Oct. 17, episode, an overdose of heroin or other opioids should be considered at least as serious as a potential heart attack, but the medical system doesn't treat it that way.

If someone comes to an emergency room with chest pain, Waller says in "Addiction," "we have a pretty standard set of approaches," and a range of options for treatment, depending on the severity of the situation.

"When somebody comes into the emergency department for an overdose, we don't have access to all the levels of care that the other standards of medicine do. And it's frustrating because these are patients who are basically dead. They are not breathing. They are this close to being dead forever," he says.

Waller, who did his emergency medicine residency at Thomas Jefferson University, until recently worked in South Jersey as the senior medical director of education and policy at the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers. There, he helped develop online education for physicians and other caregivers in the areas "surrounding addiction, pain, and behavioral health," he said in an interview over the summer after a PBS presentation for Nova.

His work, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, also focused on developing policies for dealing with "high-cost patients — the 5 percent who cost 50 percent. So it wasn't just addiction. It was really on that subset of the population … people who are in the ER multiple times, readmitted to hospitals," Waller said. "And we found that one of the largest problems and sticking points with that group is that many of them have addiction and almost none of them have adequate treatment."

Philadelphia isn't short of hospitals, but the challenges here are the same as they are in most places when it comes to offering a range of treatment for addiction, he said.

"Even with UPenn and Jefferson and Temple … each of those institutions has a little bit of something that they offer, but none of them have the full gamut," Waller said. "None of those prestigious institutions own the full ecosystem [of addiction treatment]. But they all own the full ecosystem for [treating] diabetes, for heart disease, for all these other things."

Addiction, he said, "is a complex disease that needs different levels of care," depending on its severity, but if people end up in the ER, wherever they live, it's possible their city or county "only has a detox facility. So all they can do is detox them, but then they send them right back out on the street, with no continued care. Maybe they only have an outpatient person who can help write medication, but they don't have access to intensive outpatient management, which is a very specific level of care. So the biggest issue in every city, including Philadelphia, including Camden, is that there is not a cohesive ecosystem of care for addiction treatment like there is for every other medical disease that we treat."

Chances are a Nova episode showcasing medical breakthroughs in other diseases wouldn't need to persuade viewers first that the people suffering from them deserve to be saved. We don't turn from heart patients in disgust, or attribute cancer to a lack of character. But "Addiction" acknowledges the stigma even as it challenges it, introducing people like Casey, a young woman from California who accidentally became dependent on pain pills prescribed in connection with a medical condition, and Jasen Edwards, a former coal miner from West Virginia whose addiction began after his leg was amputated due to a mining accident.

Returning to work just a couple of months later, when "my stump was still too swollen to put my prosthetic leg on," Edwards soon found himself needing more and more pain pills — easily obtained from doctors by a man with an artificial leg — just to stay on the job.

"First time I realized I was in trouble was when I couldn't go to work because I didn't have any pain pills. And it wasn't because of how bad I was hurting — it was because of the sickness due to detox," says Edwards.

Theirs are heartrending stories, but we shouldn't have to be swayed emotionally before we face facts, should we?

The sickness Edwards describes, Nova's experts say, is all about the chemical dopamine, or, more specifically, the lack of it, because, as Waller explains, the body responds to the spike in dopamine levels caused by opioids by decreasing its own production.

"Anytime someone hears the term motivation, they should really supplant that with dopamine," Waller says. "Because without dopamine, you don't have motivation. And so when we look at a person who is in the throes of an addictive disorder and we say, 'They just need to motivate,' we're telling them to somehow magically make dopamine."

"If you understand the science of addiction, then you also can look at the science of why certain treatments are effective and other treatments are not effective," Paula S. Apsell, senior executive producer for Nova, told reporters in July.

"A high percentage of the treatments that are given to people suffering from opioid addiction are 12-step programs, etc., that don't use medication," Apsell said, because of the stigma attached to addiction, which is too often regarded as something other than a treatable brain disorder that might require stabilizing patients with medication — like buprenorphine or methadone — to curb their cravings so other therapies stand a chance.

"We have large amounts of data that shows that when you apply evidence-based treatment, which is a combination of a medication with behavioral therapy, that patients do really well," Waller told me in July.

Which doesn't mean even those with health insurance can count on receiving treatment with a proven track record.

The federal government requires insurance companies "to pay for addiction treatment at parity, meaning just like you do everything else. Which is a positive thing," Waller said. "The problem that insurance companies are having is finding high-quality programs to pay. But they can't say no to even the ones that are crappy."

Watch this

Nova: Addiction. 9 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 17, WHYY12.