Philly artists’ big, urgent show at Woodmere looks out from the rowhouse to the world

In the 77th installment of a showcase for Philadelphia artists, many works invoke current issues in surprising and moving ways.

Under any circumstances, Kukuli Velarde's ceramic sculpture Saint Anna and the Virgin Mary as a Child would be a highlight of the Woodmere Annual, the Woodmere Art Museum's venerable juried show.

Here, Velarde, who was born in Peru, comes at a quasi-biblical scene from a perspective informed by the art of indigenous people of the Americas. Formally, it appears to be a dark vessel with a red clay handle sitting atop a platform painted with floral decoration.

It shows the quintessential mother figure of Western art as a daughter. The two heads emerge from the same body, a powerful, direct, yet unexpected way to express the depth of the maternal bond. Still, the two heads have distinct personalities, and their large, white, slightly uncanny eyes signal their alertness to each other. In fact, the two faces are portraits, of the artist and her daughter.

It's an outstanding piece that has been given pride of place in the gallery, and extensive discussion in the show's online catalog. The artist and the show's organizers couldn't have known that just as the show opened, U.S. immigration officers would begin a frontal attack on this maternal bond, wresting children from their parents and confining them in detention centers. Now when you look at the figures' bright eyes, maybe there is fear.

This work fulfills the implicit promise of the Woodmere Annual — to tell us something about here and something about now. That doesn't mean works ripped from the headlines, nor is the show an indicator of the latest artistic fashions. Rather, it shows us what nearby artists are looking at and what they are seeing.

Calling all artists

Each year, the museum sends out a call to artists who live or work within a 50-mile radius of the Chestnut Hill museum to submit works that needn't be brand new but that often are. A guest juror sets out some themes for the artists to consider, then makes the selection.

This year's juror is Syd Carpenter, a sculptor and multimedia artist who teaches at Swarthmore, and she asked for art that considers the natural landscape, the human body as a physical thing, and the movement of the body in time and space. She picked about 100 works by 76 artists, along with two works from Woodmere's permanent collection and a piece of her own.

As one might expect from a sculptor, this is a three-dimensional show. Even some of the wall-mounted pieces refuse to be flat.

One of these is a piece from Woodmere's collection Trayvon Martin, Most Precious Blood (2013-14) by Barbara Bullock. On a wall label, Carpenter says she picked this "drawing in space" because it represents trauma, "a bodily shudder." Before I looked at the title or the label, my reaction was simply that this wall-mounted work made of bright colored, cut and folded paper, is really beautiful.

Should I feel guilty about the pure visual pleasure I felt from this work now that I know its intent? Or is the work failing because it does not, at least for me, embody the emotional intensity to which it aspires? This is a pitfall of art that is driven by events. Most of the time, it is better to be indirect.

Shine, a 2017 photograph by Cheryl Tracy, also raises the issue of how young black men are perceived. Indeed, the name of the work is a somewhat archaic racial slur, though it is also the word on the T-shirt of the youth in the picture.

What makes the picture memorable, though, is his contemplative, peaceful attitude. He looks like a Buddha or a sage, and he even seems to be giving off a spiritual glow, a shine of his own. It challenges viewers, in a quiet way, to question their assumptions.

Of course the glow is, in large part, the artist's doing.

We know better nowadays than to view a photograph as a reliable account of reality, though it's a hard habit to break.

iPad, a 2018 photograph by Keith Sharp, is a witty, understated meditation on whether what we see on our screens is to be trusted. It is actually three photographs jointed together. One shows a landscape blocked by a balustrade, another shows an iPad, and the third, on the iPad, shows the landscape as though the barrier weren't there. That last one, on the iPad, is the most compelling, the one we most want to buy into.

Join My Swim Team, a one-minute video by Yixuan Pan, who was born in China in 1991, is a compellingly minimalist take on immigration and U.S.-China relations. The video shows only the back of a young woman's head while the headphones bombard us with admonitions, English in one ear, Chinese in the other. The voices seem to be the artist's own; she evokes what it's like to be inside her head.

The show is not just about our time, of course, but also about our place. Market/Frankford El by Leroy Johnson is a lively combined painting and photo collage of a piece of aging infrastructure. On the label, Johnson, who was born in 1938, says the El "represented a stable feature of the urban landscape in my youth and a sign of change in my senior years. It is in many ways a metaphor for the body and the journey through life."

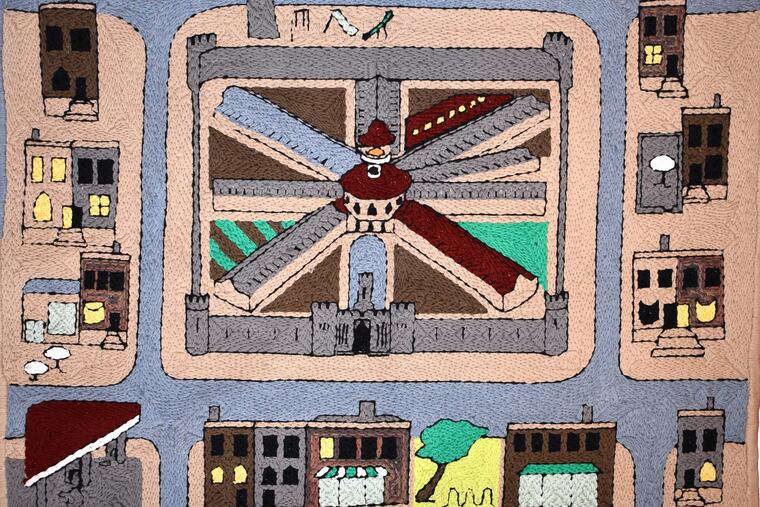

A much younger artist, Tabitha Arnold, born in 1995, takes on another local landmark in Panopticon, inspired by Eastern State Penitentiary. Arnold's work is a hooked rug that she says was inspired by the war rugs of Afghanistan. The title is about surveillance, but what's fun about the piece are the expressive faces of the city's rowhouses, smiling, looking blank, and in one instance emitting an Edvard Munch (or perhaps Home Alone) scream.

I have emphasized the ages of the artists here because the range is so great, and older artists — including some local old masters — are well represented. Chief among these is William Daley, the ceramicist and teacher born in 1925, who is represented by a 2008 work, C-Venture Vesica, an unglazed stoneware bowl.

Sometimes, even in an annual, you need something timeless.