Cheesed off

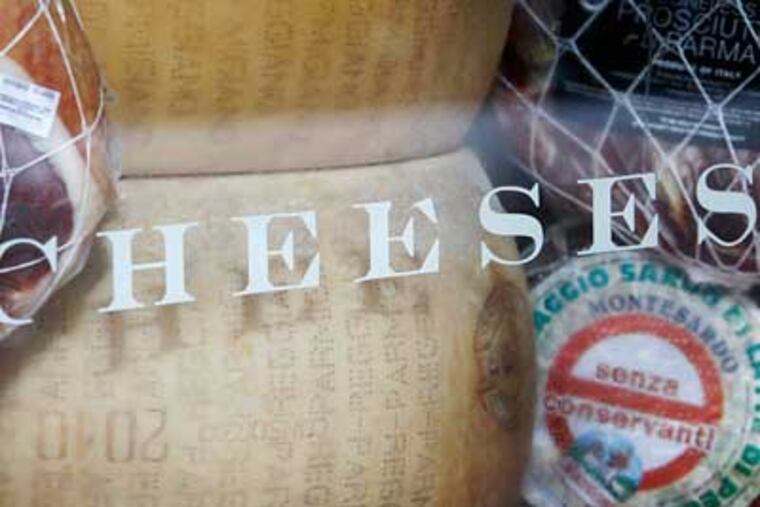

SAL AURIEMMA, owner of Claudio King of Cheese in the Italian Market, knows a phony when he sees one. And as important as that may be when it comes to people, Auriemma really gets his dander up when the counterfeit is Parmigiano Reggiano cheese.

SAL AURIEMMA, owner of Claudio King of Cheese in the Italian Market, knows a phony when he sees one. And as important as that may be when it comes to people, Auriemma really gets his dander up when the counterfeit is Parmigiano Reggiano cheese.

"Saying cheese that's made in Hungary or Wisconsin is Parmigiano Reggiano should be illegal!" said Auriemma, clearly outraged. Parmigiano Reggiano - a strong and slightly salty Italian cheese prized for its distinctive texture, aroma and taste - can only come from the Parma region north of Milan, Italy, the same rich farmland that produces true Prosciutto di Parma ham and Lambrusco wine.

Phony Parmigiano is illegal in the European Union, thanks to a 2008 ruling that cheese makers other than those in designated Italian provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena and parts of Bologna and Mantova can no longer call their cheese "parmesan" because "parmesan" is not a generic term. True Parmigiano Reggiano must be produced in its Protected Designation of Origin, or PDO region, under strict controls and practices that date back a thousand years, when Benedictine monks along the Po River first created the salty cheese to preserve milk.

"The PDO protects consumers by telling them the product actually comes from this small area in Italy where it was originally created," said Simone Ficarelli, who handles international communications for the Italian consortium that regulates and promotes the cheese producers. Unfortunately there is no agreement to follow these rules in the United States or Canada, where phony Parmigiano proliferates.

"The taste is completely distinctive," said Auriemma, who still recalls his first taste of the aromatic cheese at age 8 at his Italian family's table. "It's about the soil, the air, the grass the cows eat, the water - you can't duplicate that. All of those conditions are what gives the cheese its character."

Auriemma imports 80-pound wheels of the cheese from the Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano Reggiano, a cooperative of 382 cheese producers who work with local farmers to ensure that every cheese bearing the consortium's stamp is perfect. Auriemma knows many of the cheese makers himself - he visits Parma every other year to attend the CIBUS Parma International Food Exhibition, a showcase for food importers and distributors.

In Parma, Auriemma has seen the wall of shame. In the basement of the Parmigiano Reggiano Museum in the heart of the region of Emilia-Romagna, the champions of Italy's best-known cheese display cases of global counterfeits: Parmesan wannabes with names like Parmasello, Pamesan and Parmella. There's even a dairy-free Parmesan - laughable, since Parmigiano Reggiano has a higher percentage of milk protein than any other cheese.

That's because it takes 3.7 gallons of raw milk to make two pounds of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese and 145 gallons to produce one wheel. And that milk can only come from local cows that chew local grass. No exceptions!

The cheese-making process is done by hand following centuries-old traditions. Within two hours of the evening milking, the milk is poured into holding basins, where the cream rises to the top overnight. In the morning, partly skimmed milk is mixed with whole milk from the morning milking and warmed in copper cauldrons.

Natural whey starter obtained from the previous day's cheese is added, along with the natural enzyme rennet, which allows the milk to curdle. The cheese maker then carefully cooks the cheese, a dicey process that can make or break a good wheel.

Once the heat is turned off, the cheese granules sink to the bottom to form a compact mass that is lifted up in cheesecloth, split into two parts and placed in a rounded mold. At this point, the cheese has the texture of fresh mozzarella.

After a few days of brining, the wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano are stacked and aged for 12 to 36 months, developing a richer and sharper flavor over time.

Once inspected and its quality assured, each wheel gets stamps of authenticity (see sidebar). That's true for about 92 percent of wheels produced, which will sell for about $1,000 each. The other 8 percent, deemed inferior, are sold at a fraction of that price for commercial grating.

Towers of aging cheeses toppled back in May when two powerful earthquakes shook the region. Ficarelli said 300,000 wheels were damaged and either had to be destroyed or sold at deep discounts.

"It was 150 million euros in loss," he said. "We are doing everything we can to help these small cheese markers and farmers that were affected."

Some 37 cheese factories and 600 farmers suffered earthquake losses. Raising public awareness is one way to do this, including Parmigiano Reggiano Night, being held Oct. 27 throughout Italy.

Chef Massimo Bottura, whose restaurant Osteria Francescana earned three Michelin stars in Modena, created a risotto using Parmigiano Reggiano (see recipe). Italians have been encouraged to make the recipe and share a meal with family and friends that Saturday evening.

Despite the heavy losses, Auriemma's prices have stayed steady for the cheese, which he sells for $16.99 a pound. "Parmigiano Reggiano costs a little more, but it's worth it. . . . It's made on farms that produce only one or two wheels a day. I don't care what you call it, no cheese compares to Parmigiano Reggiano."

Food and travel writer Beth D'Addono writes about authentic travel experiences at unchainedtravel.com.