Health-care advocates see future pain in Corbett budget

If education is facing a Category 5 hurricane from Harrisburg, then public health and human services may be experiencing the calm before the gathering storms.

If education is facing a Category 5 hurricane from Harrisburg, then public health and human services may be experiencing the calm before the gathering storms.

Unlike governors of both parties in some other states, Gov. Corbett has not proposed killing any major medical-assistance programs or cutting eligibility. Spending in his budget plan is up slightly in several areas, leaving advocates for the elderly, poor, and disabled pleasantly surprised.

That feeling may be fleeting.

In the short term, Corbett's budget for the fiscal year that will begin July 1 factors in hundreds of millions of dollars in anticipated savings from "cost containment," "promoting competition," and other strategies that are not yet detailed but would come largely from reduced payments to hospitals, nursing homes, and other providers. And several smaller categories of funding that disproportionately benefit struggling major medical centers in the Philadelphia region would be eliminated.

What scares advocates more, however, is two or three years down the road, because Corbett administration officials have described the budget as only the first step in a multiyear process of sweeping changes in not just spending but also their entire approach to human services.

Corbett has promised to close a $4 billion shortfall without raising taxes in a difficult budget year. States all around the country are grappling with dramatic increases in Medicaid costs as one-time federal stimulus money disappears even as the effects of the recession linger.

"We can turn this fiscal challenge into an opportunity," Gary Alexander, acting state secretary of public welfare, said last week in a briefing on the budget, "but we will need to change our mind-set on Medicaid, in part by allowing Medicaid recipients to have a greater role in deciding how they receive treatment and giving them an incentive to make the cost of care a factor in that decision-making."

Alexander came here from Rhode Island, where as secretary of health and human services he won an unprecedented agreement from Washington to limit Medicaid spending in exchange for far more flexibility in how the money was used. The success of that overhaul is unclear. What is clear is that Pennsylvania faces different challenges from Rhode Island and many other states.

Pennsylvania, for example, spends a much greater proportion of its general fund on Medicaid (31 percent) than several other large states, including New York (27 percent) and New Jersey and California (both at the national average of 21 percent).

But Pennsylvania is not particularly generous in benefits or eligibility, and the Corbett administration acknowledged that former Gov. Ed Rendell had managed to keep the rate of increases in health-care spending well below the national trend.

The problem with Pennsylvania is Pennsylvanians.

"We're old. We spend a lot of money on long-term care," said Sharon Ward, executive director of the independent Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center.

While Medicaid is often described as the joint state-federal program for the poor, nearly three-fourths of Pennsylvania's portion goes to long-term services for the elderly and disabled.

The Keystone State has one of the highest percentages of older residents in the nation. And it cares for more of them in institutions rather than in their communities: 67 percent of Pennsylvania's long-term care is in nursing homes vs. 60 percent nationally. Institutions cost more, and the new governor, like his predecessor, is hoping to help more people at home.

"It seems like the administration is valuing community and home-based care," said Jonathan Stein, the general counsel of Community Legal Services of Philadelphia. "That is a win-win. Save money, and give older people care outside of nursing homes."

Stein has been one of the fiercest critics of Corbett's decision to end adultBasic, the state-subsidized insurance program for adults who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to afford private insurance. The loss of coverage for those 41,000 people last month is the biggest cut to human services so far.

And there is a ripple effect.

"What happens with these folks is they wind up in the hospitals for care. They're going to get sicker," said State Sen. Vincent J. Hughes (D., Phila.), minority chairman of the Appropriations Committee.

The budget would kill several categories of supplemental medical assistance intended to support hospitals that serve large numbers of poor and uninsured patients or use more resources to train medical students or provide special care, such as trauma and burn centers. Many are concentrated in Southeast Pennsylvania. Matching federal funding would be lost as well.

Even after poring over the budget for several days, hospitals were still trying to grasp the effect of what they said seemed to be far more significant, undetailed cost-containment decreases masked by larger increases that are required because of increasing numbers of patients.

"What we know is that this is a devastating budget to us," said Kenneth J. Braithwaite, director of the Delaware Valley Healthcare Council. Health care tends to lag 12 to 18 months behind the general economy, he said, so hospitals are struggling with a continuing drop in revenue while treating more uninsured patients.

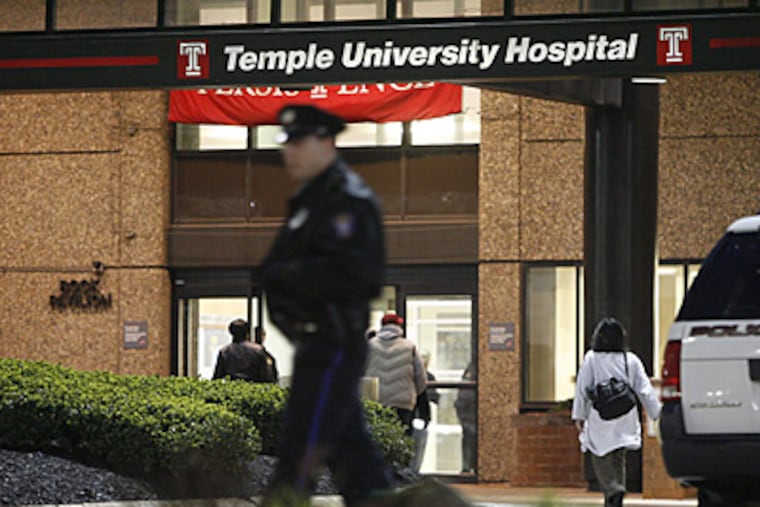

Temple University Hospital would probably be hit hardest. It serves a greater number and a higher proportion of Medicaid patients than any other hospital in the state. It also receives more funding from more of the Medicaid categories proposed for elimination - for trauma, burn, state-related academic medical centers, and more - than any other hospital.

Those losses plus estimates of the undefined cuts "could approach $83 million" - 26 percent of the Temple system's medical-assistance payments - spokeswoman Rebecca Harmon said. Temple is already against the ropes, having reported a $35 million operating loss last year.

Even if the dire projections turn out to be true, the state's general-fund portion of the Department of Public Welfare budget next fiscal year would be nearly 27 percent higher than it is now, partly as the state replaces one-time federal stimulus funding.

Total spending - state and federal - would increase 0.3 percent. (Total basic education spending, by contrast, would fall nearly 11 percent.)

Future years will likely see bigger moves.

The Department of Public Welfare "cannot make wholesale changes in one fiscal year," spokesman Michael Race said. "For the most part, education is funded with state dollars, and they don't have many of the strings attached that we do with the medical-assistance budget."

Overall, the administration is seeking to "change the mind-set" of dependence on public assistance, Race said.

Although some people have long-term disabilities that require continuing care, the "safety net" for many others originally was "meant to be a short-term way to get you back on your feet," he said, "toward independent lives and independent decision-making."

The plan is to return to the original intent.

Pa. Human Services Budget

Gov. Corbett proposes a 26.6 percent increase in general-fund support next year for the Department of Public Welfare - the biggest chunk of the state budget - partly to replace onetime stimulus money. The agency's state and federal spending combined would be $27.6 billion, up 0.3 percent from this year.

The bulk of the funding would be for Medicaid, the state-federal program for elderly, poor, and disabled residents that reimburses hospitals, nursing homes, and others for services.

Some examples of changes:

Major categories of Medicaid spending are up * . . .

Total state and federal funding, in billions.

2010-11 2011-12

Managed care $8.99 $9.41

Outpatient (fee for service) $2.00 $2.04

Inpatient (fee for service) $1.81 $2.01

Long-term care $3.76 $3.86

* Statewide increases are mostly mandatory, largely reflecting more use of services.

In each category are as-yet-undefined savings that hospitals fear could be devastating.

. . . but smaller categories disproportionately affecting Philadelphia** are down

Total state and federal funding, in millions.

2010-11 2011-12

Physician practice plans $28.8 0

State-related academic med. centers $44.3 0

Trauma centers $25.9 0

Hospital-based burn centers $11.4 0

Obstetric and neonatal services $10.8 0

** Physician practice plans: Medical schools at Drexel University, Thomas Jefferson University, and the University of Pennsylvania are the only recipients statewide.

State-related academic medical centers: Temple, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center are the only ones statewide.

Trauma centers in region: Abington Memorial Hospital, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Aria Health-Torresdale Campus, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Crozer-Chester Medical Center, Hahnemann University Hospital, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Paoli Hospital, St. Christopher's, St. Mary Medical Center, Temple, Jefferson.

Burn centers in region: Crozer-Chester, St. Chris, Temple.

Hospitals in the region that get funding for obstetrics and neonatal services: Abington, Einstein, Jennersville Regional Hospital, Chester County Hospital, CHOP, Crozer-Chester, Delaware County Memorial Hospital, Hahnemann, HUP, Mercy Suburban Hospital, Montgomery Hospital, Pennsylvania Hospital, Pottsville Hospital, St. Chris, Temple, Jefferson.