DHS overhauls structure to set clear lines of accountability

Philadelphia's Department of Human Services is planning an extensive reorganization aimed at reducing confusion over who is responsible for abused and neglected children in its care.

Philadelphia's Department of Human Services is planning an extensive reorganization aimed at reducing confusion over who is responsible for abused and neglected children in its care.

Under the current system, DHS caseworkers, their supervisors, and outside social service contractors often are assigned to the same case. There are no clear lines of accountability and often work is duplicated.

Under the proposed structure, DHS would do initial intake and investigate cases, but would turn over follow-up care to outside contractors. DHS would plan for and monitor a child's care, but would not provide it. The department also would help make key decisions, such as whether to remove a child from parents or caregivers.

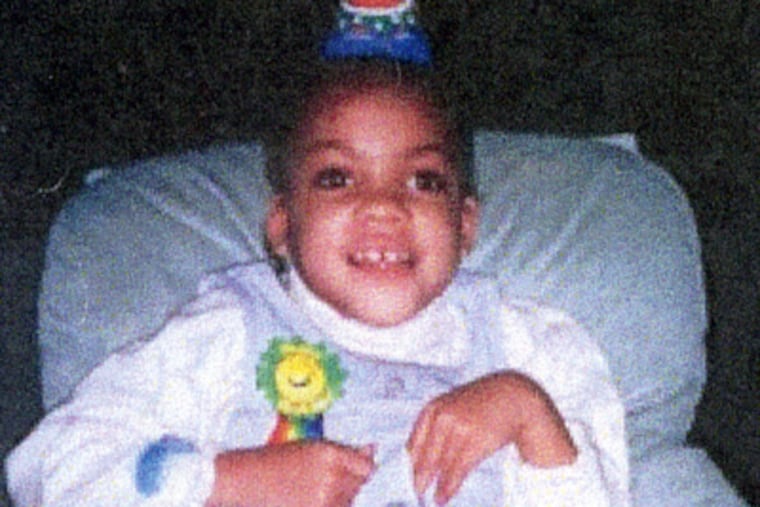

The plan is in response to the deaths of children over the last decade and is the latest in a series of efforts to fix a system that contributed to the 2006 death of 14-year-old Danieal Kelly, who had cerebral palsy and could not care for herself. The story of Kelly's death shocked the city and led to the convictions of two social workers, one a DHS employee and the other a contractor.

Kelly's medical care fell through the cracks because neither agency properly monitored her case.

"This is intended to provide clarity where we had major confusion that resulted in tragedy," DHS Commissioner Anne Marie Ambrose said of the proposed structure. Mayor Nutter appointed Ambrose to lead the agency and make changes.

The overhaul would also shift the care to neighborhoods, where the contracted agencies, in theory, should have a better sense of a family's and community's problems. Currently, DHS staffers have an average workload of 13.5 cases each, and those cases are often in different neighborhoods.

DHS serves about 100,000 children and families. The proposed structure initially would affect only about 6,000 children who receive in-home and placement services.

Ambrose said the need to streamline the system became clear when she was talking to a foster mother who was not sure who her DHS worker was because the mother was caring for three children. Each child had two caseworkers, one from DHS and the other from a contractor. The caseworkers sometimes gave the mother conflicting advice about what to do.

"When everybody's responsible, nobody's responsible," Ambrose said.

Representatives of DHS and many other groups, including AFSCME District Council 47, the union that represents many DHS employees, and the Support Center for Child Advocates, have been working on the plan since late last year. Ambrose expects to implement it over four years starting in 2012. The first phase of the neighborhood program would cover Kensington, Olney, and other sections of North Philadelphia, according to Alicia Taylor, a DHS spokeswoman.

State officials will have to weigh in on the changes, and DHS still has to negotiate some of them with the union.

The change won't be easy. Some families require more than one caseworker because children have different needs. One may have cerebral palsy while another is a victim of sexual abuse, for example.

But the concept is to make sure that only one contractor is responsible for coordinating that care.

Legally, DHS will still be accountable.

Frank Cervone, executive director of the support center and a member of the group that devised the plan, said he hoped it would clarify responsibility.

"Having all these cooks in the kitchen has been part of the problem. It hasn't been part of the solution. What we have today is finger-pointing," Cervone said.

He said, however, that the overhaul might not work because the problems are overwhelming.

"It's unclear whether they are going to be able to pull it off, because this is a very hard job when the service array is so varied and the needs of the families and children are so challenging," he said.

Ambrose said she did not expect the changes to result in layoffs because she thought DHS caseworkers would shift to new roles in intake, training, and oversight.

There are 1,674 DHS employees; about 830 are caseworkers. DHS contracts with about 250 outside organizations to provide services to all of the children and families who come in contact with the child welfare system, including children who have been through Juvenile Court.

Ambrose said she decided to have contractors do most of the casework because it would have been too expensive for the city to hire enough workers to monitor all the cases themselves.

Rita Urwitz, vice president of D.C. 47, said she was concerned that the new structure would reduce oversight, not increase it.

"DHS workers will not be involved with the case," she said. "You have one set of eyes on an entire family."

D.C. 47 represents about 600 DHS social workers and 140 supervisors.

Ambrose was surprised at Urwitz's comments because the union had been involved in the entire planning process. Urwitz said the union had been involved in discussions but not final decisions, though Ambrose said the union did not say anything about problems when it was informed of the proposed change.

Danieal Kelly died in 2006 in a filthy two-bedroom apartment she shared with her mother, Andrea, and eight siblings. She weighed only 46 pounds at her death and was covered in bedsores.

An Inquirer series that year reported that from 2003 through 2005, 20 children died of abuse or neglect after they or their families had contact with DHS.

Andrea Kelly, 42, pleaded guilty to a third-degree murder charge in 2009 and is serving a 20- to 40-year prison term. Danieal Kelly's father, Daniel, was found guilty of child endangerment.

Dana Poindexter, a DHS social worker who was supposed to have investigated reports of Kelly's abuse, was convicted of child endangerment, recklessly endangering another person, and perjury.

Mickal Kamuvaka, head of MultiEthnic Behavioral Health Inc., a DHS contractor that was paid to put a social worker in Kelly's house twice a week, was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter, child endangerment, reckless endangerment, perjury, criminal conspiracy, and four charges involving creation of a falsified case file to make investigators think Kelly got in-home services.

Daniel Kelly, Poindexter, and Kamuvaka await sentencing.