Artist-neuroscientists light up the brain

In a corner of Greg Dunn's Spring Garden studio are two cabinets. One holds the sources for the science - Cajal's Butterflies of the Soul, a book of figures from the 19th and early 20th centuries focusing on the brain, and The Color Atlas of Anatomy.

In a corner of Greg Dunn's Spring Garden studio are two cabinets.

One holds the sources for the science - Cajal's Butterflies of the Soul, a book of figures from the 19th and early 20th centuries focusing on the brain, and The Color Atlas of Anatomy.

The other cabinet keeps the elements of his art. Mica powders, soft and glittery. Weightless tissue papers holding a variety of gold leaf - white gold, champagne gold, yellow gold.

Dunn's work melds science and art, bringing images of the brain into beautiful, ethereal detail. This summer, the California native with a doctorate in neuroscience from the University of Pennsylvania collaborated with Brian Edwards - whose Penn doctorate is in electrical engineering - to develop the "Mind Illuminated" show at the Mütter Museum.

The duo, who met eight years ago in graduate school and started making art together in 2013, say the branches and twists of the brain are just as art-inspiring as any landscape.

"Our work is sometimes treated as kitschy nonsense - 'Oh look, the scientists are trying to do art' - and it's tragic because there's so much inspiration there," Dunn said. "When you look through a microscope and see a landscape of the brain and paint it, the only thing that differentiates between that and a landscape of a forest is that you needed a tool to look at it."

It's one of many ways in which scientists are moving toward the artistic. At several medical schools in the area, for instance, students take drawing, painting, and other arts classes along with gross anatomy. The hope is they will enhance their powers of observation, including in their dealings with patients.

Dunn has always been a bit of a Renaissance man, playing the piano when he was 5, later making albums with a band. He considered becoming a monk in his early 20s, and still meditates regularly.

He said scientific research alone, with its years of constant testing, didn't satisfy his need to produce something tangible. His first images were ink on parchment or rice paper. At first he used a brush, but one day he used his breath.

"The ink just exploded into these beautiful tendril-like patterns," he said. "It simulates how neurons actually extend the axon through a milieu of branching cells - it grows in twists and turns because the environment is so compact.

The result is almost like a piece of lace, but its pattern also can be appreciated from afar.

Or get up close, to a piece like Microglia and Astrocytes, titled for cells involved with the central nervous system, and see the complexity of the structure, the way simple branches explode into gold streaks. Or an ink-on-22-karat-gold-leaf piece such as Basket and Pyramidals, in which jellyfish-like creatures floating in a golden sea are really replicas of neurons found in different areas of the brain.

When Dunn met Edwards, the work moved to a deeper level - literally. Edwards, who focuses on nanotechnology and optics as a research scientist at Penn, wrote computer code to be able to add movement to two-dimensional images. They describe it as a photolithographic process similar to making silicon chips for computers.

"The basic premise is: Imagine you took a mirror and put a scratch in it. All the light is going to hit that mirror and that scratch has made a tiny little shelf off of which the light is going to bounce, and your eye is going to be instantaneously drawn to that scratch because it's breaking up the way the surface normally reflects," Dunn said.

"Now make a zillion tiny scratches and draw the shape of a neuron in the scratches. There's no pigment on the metal or the page. It's the light that makes the movement."

Edwards, 35, wants viewers to have an individual experience with each piece.

"I think of it like the moon on the water - you'll see a shaft of light across the water," Edwards said. "But where that light appears will change depending on the wind or the location of the moon or where you're standing."

A self-described "nuts-and-bolts guy," Edwards wants viewers to feel almost slightly overwhelmed by the amount of detail without being confused.

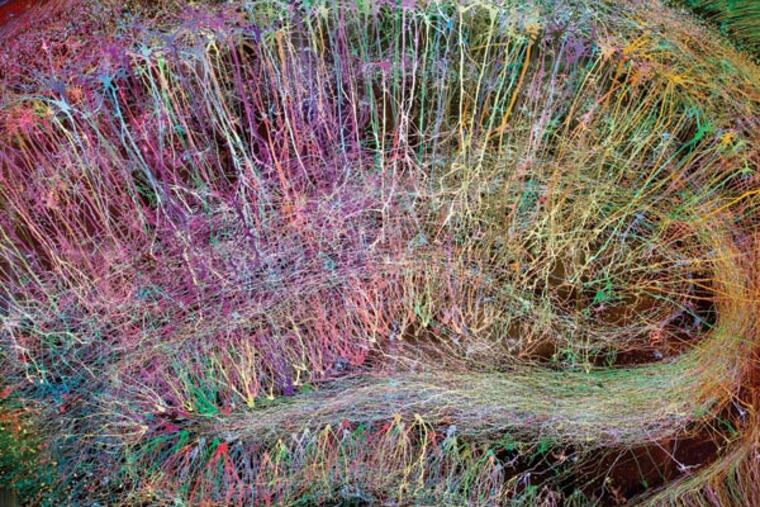

Brainbow Hippocampus, a gold-on-steel microetching of a rodent hippocampus, shows the area of the brain linked with learning and memory. Using a simple overhead lamp, it shows neurons appearing and disappearing. But multicolor lamps cause each neuron to take on its own hue, a tangle of red and blue and yellow, expressing the individuality of each neural cell.

The image changes as one moves around the piece, adding to the experience.

The works are selling well enough to support the duo - microetchings such as Brainbow Hippocampus have sold for $35,000, and scrolls fetch in the range of $1,000 to $2,000.

The pair received a $250,000 National Science Foundation grant to create an 8-by-12-foot microetching of the brain for the Franklin Institute to be called The Big Brain. The exhibit is slated to open in the spring.

The exhibit will also aim to demonstrate how the mind receives and processes sensory input. Ultimately, Dunn and Edwards want to create a laboratory of art and science, coordinating with researchers and artists nationally, funded by sales of prints and transparencies from The Big Brain exhibit.

For all their success, they are frustrated by being kept in the "science art" niche. They prefer to call their work "neo-naturalism." They don't expect everyone to like their work, these artists and scientists with no fine-art training who use technology to make art that couldn't have existed 20 years ago.

"What we aspire to is a certain degree of humbleness as we go into the art world," Edwards said.

"We want to do well and be competitive and do interesting work in the context of the currency in the art community, and there will be a learning process to figure that out."