Helping mentally ill inmates find their way home

WERNERSVILLE, Pa. - When Henry Hamm, a 61-year-old Lancaster man who has schizophrenia, finished serving time for writing a bad check, he was sent to a new program designed to help offenders with serious mental illnesses rejoin the outside world.

WERNERSVILLE, Pa. - When Henry Hamm, a 61-year-old Lancaster man who has schizophrenia, finished serving time for writing a bad check, he was sent to a new program designed to help offenders with serious mental illnesses rejoin the outside world.

He joined Pathways Transitional Wellness Center, which connects mentally ill parolees to social and medical services, housing, and jobs before they try to make it on their own.

Three months later, he's a fan of the nine-month-old Department of Corrections program, which is housed in a boxy, utilitarian building on the grounds of Wernersville State Hospital, about nine miles southwest of Reading.

"If you give into this and do what they say, you'll come out a winner," Hamm told a small group of reporters who were invited to tour the facility Tuesday.

Pathways is the first halfway house of its kind in Pennsylvania run by the Corrections Department, although contractors offer less-comprehensive programs. The state runs 14 transitional programs and contracts out almost 50 others. Ten of those, including five in the Philadelphia area, accept severely mentally ill offenders. Officials hope Pathways will become a model of broader services for a population in need of more help.

John Wetzel, secretary of the Department of Corrections, said Pathways is part of his department's response to a report four years ago that faulted the prison system for placing too many mentally ill inmates in solitary confinement, making them even sicker. "Those allegations were 100 percent accurate," he said.

Since then, the state has stepped up efforts to identify inmates with mental illnesses and provide care for them, Wetzel said. They tend to stay in prison longer than healthier peers, and are more likely to have alienated the friends and family members who could help them after their release.

This year, the department plans to work with a county to examine how gaps in community services are contributing to the arrests of people with mental illnesses.

About a quarter of the state's 50,000 inmates have a mental illness. Eight percent have the most serious diagnoses: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. Pathways serves that group. It is meant for parolees returning to six nearby counties - Berks, Lancaster, Lebanon, Lehigh, Northampton, and Schuylkill.

The 32-bed program has parole officers and counselors on site. It operates under the recovery model, the idea that people with serious mental illness can get better. Residents can sign up for Medicaid while there. Their time at Pathways is structured and their reentry is slow, an approach that Wetzel said has proven effective for high-risk offenders.

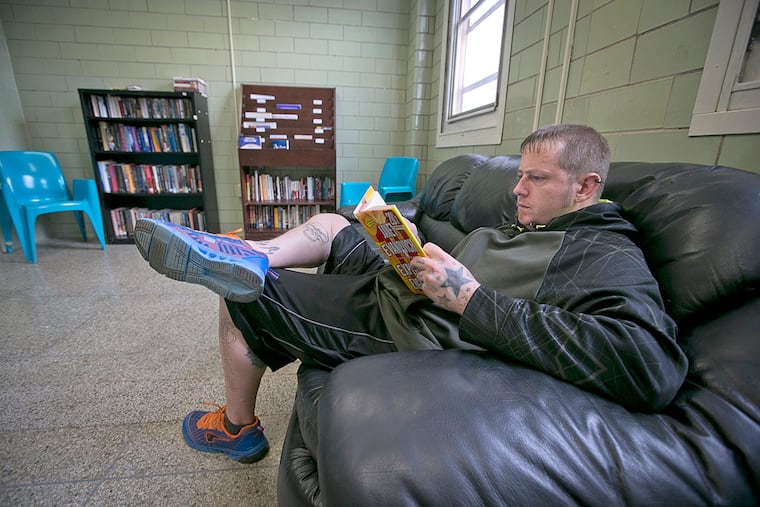

Residents share dorm-like rooms and a big activity area with an overhead TV, hard plastic chairs, and a ping-pong table. During the tour, some were attending a discussion on accepting their diagnoses and the need for treatment. Inspirational posters lined the wall. "Anger makes you smaller," one declared. "We should not let our fears hold us back," said another.

David Kopinsky, who directs Pathways, said many residents are nervous about going home after years behind bars. Employees of outside programs come to Wernersville to meet them, easing their fears. The expectation is that most will stay from six months to a year.

About 60 percent of the residents, who are allowed to leave the grounds for five to eight hours a day, have jobs.

Three residents picked by the program praised their care and said they expected to get adequate help when they leave.

Joseph Rivera, 37, of Schuylkill County, said he was proud of his restaurant job. "They help you, but they don't spoon-feed you," he said. "You've got to go out and get it."

Jeremy Gordon, 33, who was in prison for theft and struggles with depression, said the program's structure "makes it a lot easier for me to stay sober and stay clean."

Gordon, a Wernersville native who was addicted to opioids, said he has not been able to work because of health issues, but hopes to one day become an addictions counselor.

"Even if I can help one person not end up like I did, that's worth it," he said.

215-854-4944

@StaceyABurling