What addiction science says about getting - and staying - off opioids

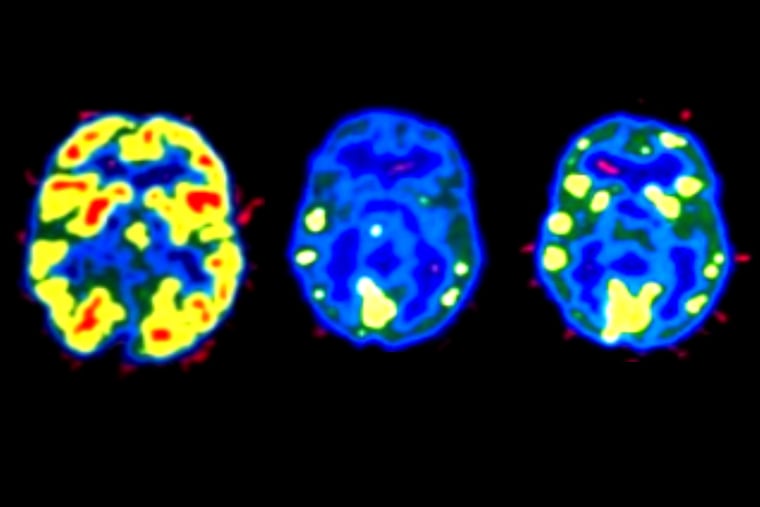

Two insights over the last half-century have transformed scientific understanding of the nature of addiction: It changes how the brain remembers and responds to temptations. You can see the difference on scans. That's why "just say no" just isn't effective.

Two insights over the last half-century have transformed scientific understanding of the nature of addiction:

It changes how the brain remembers and responds to temptations. You can see the difference on scans. That's why "just say no" just isn't effective.

It is a chronic disease, like diabetes. Both need to be managed for a lifetime. That's partly what is meant by being "in recovery."

Sidebar: How to Find the Best Treatment

Nearly 130 Americans die of drug overdoses every day, 60 percent of them - the fastest-rising category of fatalities - due to opioids. The vast majority never got help.

Many addicts may not think they need it, and their loved ones may not know what kind of help to seek.

Understanding how the brain responds to stimuli and why addiction is considered a chronic disease can help decipher the complicated world of treatment.

And these insights provide a framework for thinking about some questions facing families trying to save their loved ones: How long does treatment take? Are drugs really necessary to get off drugs?

And the biggest question: Why does treatment so often fail?

Some of the answers are surprisingly similar across addictions, whether the cause is gambling or alcohol or opioids.

There is, however, a crucial difference with that last class, mainly heroin and prescription pain pills: Relapse can be fatal. Even the best treatment can promise no more than to lower that most serious risk.

"There is no magic bullet. Part of the problem is that treatment has marketed itself as being 'the fixer.' And families think you send someone away to get fixed," said Beverly J. Haberle, who has guided desperate parents for decades.

Haberle is executive director of the Council of Southeast Pennsylvania, the regional affiliate of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. She is by no means negative about treatment.

She suggests thinking about it - no matter what type or how long it lasts - as "providing a stabilizing opportunity." It offers a timeout to begin the years of work, supported by a full team of friends, family, and employers, that is necessary for a sustained recovery.

The University of Pennsylvania has long been a leader in research on treatment for addiction. Naltrexone, a medication that blocks the effects of opioids, was first studied here, to treat alcoholism among veterans at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center in the mid-1980s.

For centuries, opiate addicts had described the cravings that would force them back to the drug. The psychiatrist who oversaw the VA work, Charles P. O'Brien, in 1977 published evidence that opioid withdrawal symptoms are, at least in part, the result of classical conditioning, like in Ivan Pavlov's dogs.

Now, with the advent of advanced imaging techniques, brain responses can be seen on scans.

"You give them a cue" - the odor of cocaine, for example, or photos of people using it - "and the brain lights up as if you have just given them cocaine," said O'Brien, who founded Penn's Center for Studies of Addiction. "You can't say no when you are out of control and actually addicted."

Genetics, history and more

How long it takes to extinguish a conditioned response depends on a combination of genetics, family history, how long the addiction has lasted - and the form of treatment.

"Generally, for residential or outpatient treatment, participation for less than 90 days is of limited effectiveness, and treatment lasting considerably longer is recommended," according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Insurance coverage has improved significantly in recent years due to state and federal laws but rarely goes that far, said Deb Beck, president of the Drug and Alcohol Service Providers Organization of Pennsylvania. "What we see typically is too little treatment," she said.

Understanding your own emotional responses is the toughest challenge in - and after - treatment, said Daniel D. Langleben, a psychiatrist at Penn. Langleben has been using functional MRI (fMRI, an imaging technology that shows brain activity) to measure opioid addicts' responses, before and during treatment, to pictures of people popping pills.

His work shows why release from treatment is actually the most dangerous time for an addict.

"They think they are fine," Langleben said.

In fact, the process of extinguishing the conditioned response has merely begun. A bit of stress - or simply running into old friends - can be enough to trigger symptoms of withdrawal. So they score some heroin or buy some prescription painkillers, just as they used to do.

After a period of abstinence, however, even though the brain may respond to temptation, the body's tolerance for opioids is gone. The dosage that once yielded a brief high now can lead to an overdose.

This, experts say, is not an occasional scenario. People who are detoxed and released after short treatment will almost always relapse (although not necessarily overdose).

What kind of support works?

Staying clean usually means changing your life, no matter what type of treatment or how long it lasted. Enlisting all the positive influences, finding coaches, altering your social circle to avoid the cues associated with using, and, for some people, leaving their hometown entirely, may all be needed.

The rules and principles of 12-step programs can help, but research shows that they alone are not enough for most people. Medications, however, have a proven track record - provided that they are used in conjunction with behavioral work.

Medications offer a kind of breather - reducing how the brain responds to triggers during the long period of essential behavioral work.

Some people are able to taper down from these meds after six months or a year. Some never can, though data are scarce. Research indicates that people who use the medications stay in treatment longer, and are far less likely to overdose.

Using drugs to get off drugs troubles some families, and many treatment centers that have been around for years, often with no physician on staff, started working with medication only recently.

Adam C. Brooks, who studies the effectiveness of different treatments at the Philadelphia-based Treatment Research Institute, is blunt. "Programs that are not willing to integrate medication into their approach are taking a risk with their patients' lives," he said.

Many do offer meds, and those programs are often the best option, he said. Conversely, some independent physicians who have been trained and certified to prescribe treatment medications may be "running loose practices," Brooks said, adding that medication without psychotherapy is "a recipe for failure."

Meds that help kick drug habits

There are three categories of treatment medications:

Methadone, which has been used in treatment since the 1960s, is an opioid agonist: It binds to the same receptors as heroin and prescription painkillers, so users avoid withdrawal symptoms, but without the euphoric effects. It must be used carefully for safety reasons and is tightly regulated, typically requiring daily visits to a clinic. Good clinics work the behavioral therapy into that schedule.

Buprenorphine, approved in 2002, is a partial agonist: It is weaker (but lasts longer) than methadone, and can be prescribed monthly by certified physicians. Like methadone, it is an opioid.

Buprenorphine is most commonly sold as Suboxone, a combination with the opioid-blocker naloxone. In theory, the opposing drug is released only when the pill or under-the-tongue film is crushed and snorted or injected, making abuse less likely. A six-month implant called Probuphine was approved last month by the Food and Drug Administration.

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist: It blocks those same receptors. Someone who took opioids, legitimately or not, within the previous one to two weeks would immediately go into withdrawal on naltrexone. Used after a period of abstinence, however - during inpatient treatment, or prison - the drug prevents all effects of opioids taken subsequently.

The FDA approved a one-month naltrexone injection marketed as Vivitrol in 2010; extended-release is now the most common version.

Still, naltrexone, which cannot be abused, lags far behind methadone and Suboxone as a treatment medication. You can't go directly from heroin to naltrexone without detoxing. And it is less popular among people in recovery.

Abstinence from opioids can lead to a sort of low-level anxiety, which naltrexone does not change. On methadone, by contrast, "you just sort of feel normal, you are not in withdrawal, and you're not high," said George Woody, a professor of psychiatry at the Philadelphia VA hospital who has authored dozens of studies on medication-assisted treatment.

He is just starting a new one to measure the impact of extended-release naltrexone on volunteers being released from Philadelphia's prisons. A small study led by O'Brien recently showed relapse rates cut by one-third, and many prison systems are already using it.

Jeffrey H. Samet, an addiction specialist and chief of internal medicine at Boston University, says that concerns about using drugs to get off drugs - and how long you'll need to be on them - are misplaced.

"The key is we want you recovered. It's like diabetics. We want you off insulin. Some can do it, some can't. It's comparable," said Samet, whose clinics at Boston Medical Center treat tens of thousands of patients.

In fact, other researchers have calculated that drug addicts relapse about as often as people with high blood pressure and asthma fail to follow their recommended maintenance regimens.

Done correctly, Samet said, treatment for addiction can be pretty successful.

Doctors in the emergency department, where Samet practiced for 10 years, see the failures.

"But people in recovery," he said, "they are living life."

215-854-2617

@DonSapatkin