A medical resident on ‘imposter syndrome’: It’s an anchor, not a weight

I thought the admissions committee at Sidney Kimmel Medical College must have made a mistake when they let me in. I kept thinking that I am not smart enough nor do I possess the endurance necessary to become a real doctor. Who was I kidding?

When I was a medical student rotating through clerkships, I had a few rough goes and questioned if I was really cut out for this profession.

I thought the admissions committee at Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University must have made a mistake when they let me in. I kept thinking that I am not smart enough, nor do I possess the endurance necessary to become a real doctor. Who was I kidding?

I came to learn that this phenomenon has a name: "imposter syndrome."

Apparently, it's quite common and, I think, rampant in medicine.

On a particularly disheartening day during my clerkship a few years ago, I wandered into the office of my mentor, a hepatologist who is revered both for his vast clinical knowledge, and for his kind and genuine heart.

I always looked up to him. For one thing, he, like me, came to medicine through an unconventional route.

As a child with Type 1 diabetes, I had far more exposure to doctors and medical information than any kid should. While I developed a fascination with medicine, my strengths were in drawing back then. Eventually I channeled my artwork into a handy way to remember anatomy lessons, and also into a superhero comic to help children facing Type 1 diabetes better understand their disease. But because of my struggles with math and science growing up, it was not until I was out of college that I thought medical school was even an option for me. In many ways, I consider myself a patient first and a doctor second.

My mentor, Steven Herrine, was a classically trained chef and had a successful career before changing paths to become a doctor. (We even grew up in the same New York City neighborhood and attended the same tiny high school.)

On that day, I plopped down in a chair in his office and began to vent. I expressed my feelings of inadequacy, of feeling like I was a fraud. And then he said something that has stuck with me ever since:

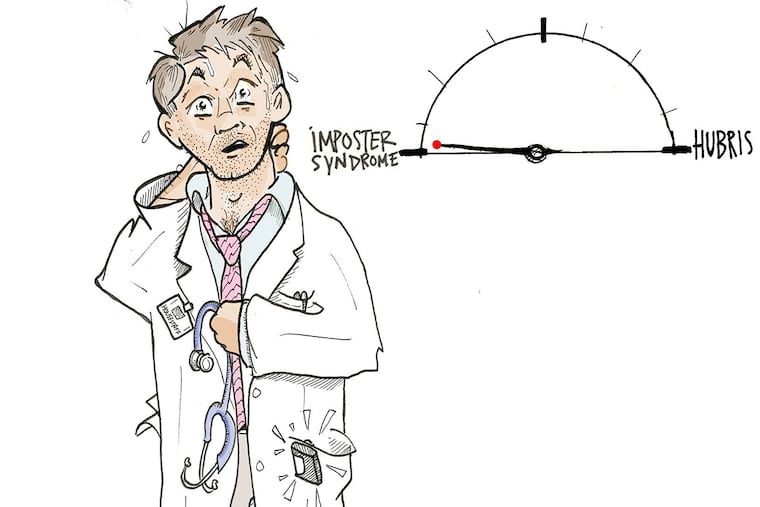

“Mike, we all have imposter syndrome. Every time I put my white coat on and talk to my patients, I feel that weight of being an imposter. But what you have to keep in mind is that once you start to drift away from that imposter syndrome, you risk edging closer toward hubris. Allowing your imposter syndrome to anchor you but without weighing you down is the goal.”

“Mike, we all have imposter syndrome. Every time I put my white coat on and talk to my patients, I feel that weight of being an imposter. But what you have to keep in mind is that once you start to drift away from that imposter syndrome, you risk edging closer toward hubris. Allowing your imposter syndrome to anchor you but without weighing you down is the goal.”

July is when teaching hospitals are flooded with bright-eyed, newly minted doctors. Undoubtedly, many of these fresh faces will be questioning themselves, battling their own feelings of imposter syndrome, as they put on their long white coats. While that feeling can be quite burdensome, it's important to remember Herrine's message: The right dose of imposter syndrome can keep us grounded and, in turn, help us to become better doctors.

Imposter syndrome might not be so bad after all.

Michael Natter, M.D., a graduate of the Sidney Kimmel College of Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University, is in his second year of his internal medicine residency in New York City. Follow his journey on instagram @mike.natter and Twitter @mike_natter.