Philadelphia women’s prison tries bold move to save lives: Give inmates a treatment opioid

Since February at Riverside Correctional Facility, the city women's prison, doctors have been prescribing inmates Suboxone — one of the medication-assisted treatments proven to give opioid users the best shot at recovery. The Suboxone program is expanding to the rest of the prison system this month.

For six months, Philadelphia has been at the vanguard of a quiet national experiment: providing prison inmates with an opioid-based medication to help protect them from heroin overdoses when they are released.

Since February at Riverside Correctional Facility, the city women's prison, doctors have been prescribing inmates buprenorphine — one of the medication-assisted treatments proven to give opioid users the best shot at recovery. The program is expanding to the rest of the prison system this month.

In a normal clinical setting, buprenorphine is used to boost the success of long-term treatment. And while some inmates do use their time in jail to start on treatment, the prison sets its minimum goal to keeping the women's opioid use — and tolerance — from dropping to zero, which would make them far more vulnerable to overdose if they return to using on the outside.

Inmates in Philadelphia's prison system — where about 76 percent of the population struggles with a substance use disorder — are particularly at risk of overdosing, in part because most of the city's drug supply has been contaminated by the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl, which often is added to drugs without the user's knowledge.

>> READ MORE: Fentanyl is killing more Philadelphians than any other drug.

Of the 2,522 people who died after their release from city prisons between 2010 and 2016, a third died of overdoses, according to a city health department study published in the scientific journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence this month. And former inmates were particularly at risk in the first two weeks after their release. (It's too early to tell whether the new buprenorphine program has had an effect on overdoses among former inmates, prison officials said.)

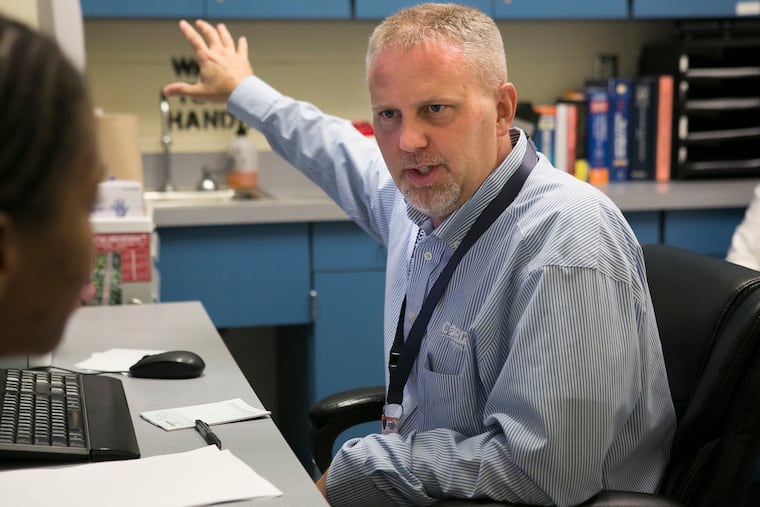

Jon Lepley, the physician who pioneered Philadelphia's buprenorphine program, said that before this year, he would often hear from his patients about inmates who had overdosed after leaving prison. "It would be, 'Did you hear this person died? And this person died?'" he said. "That really changed my views on [buprenorphine]. I really came to see it as life-saving."

Last week, he met with a few women started on the program for follow-up appointments in the prison's medical wing. One was due to be released just a few days later; they spoke about getting her into a treatment center near her house.

Another spoke of her time detoxing during prior prison stints, spending up to two weeks suffering the intense nausea and pain of withdrawal, hoping she would have an understanding cellmate to help her through.

"When you came in and you detoxed in here before, 100 percent of the time, you really thought about drugs," another woman on buprenorphine said in an interview. "Now, I don't crave anything, I don't have drug dreams, and when I leave, I think I really have a good chance of not relapsing." (The prison allowed the inmates to be interviewed on the condition that their names not be used.)

The prison's health staff was inspired by the success of a similar program in Rhode Island state prisons, which prescribed buprenorphine and two other types of medication-assisted treatment to inmates and encouraged them to stick with treatment after leaving prison. A study published in JAMA Psychiatry earlier this year found the program led to a 60.5 percent reduction in overdose deaths in the first six months of 2017, compared to the same period the previous year.

"I'm delighted it's happening and moving forward in Philly — you guys are blazing trails," said Traci Green, the Brown University researcher who conducted the study and advises Rhode Island's governor on the opioid crisis. She said since the study's publication earlier this year, she has fielded dozens of requests for information from state and city governments.

But stigma against treating an opioid addiction with an opioid-based medication makes it difficult to convince some prison officials to provide these kind of treatments in a correctional facility: In some jails, patients are even required to stop taking addiction treatments like methadone. (That's not the case in Philadelphia — while inmates can't enter a methadone program from jail, patients already established on methadone treatment are allowed to continue once inside.)

Only a few places, including Riverside and New York's Rikers Island Correctional Facility, have started medication-assisted treatment programs.

>> READ MORE: She was just out of rehab. She was excited about the future. Three hours later, she was dead.

Lepley is adamant that what he's offering is a public health measure, not a "highly individualized" treatment program. The average stay at Riverside is 14 days — not nearly long enough for the kind of intensive treatment that patients with opioid addiction require.

And in a normal clinical setting, buprenorphine doses are tailored for each patient's needs. At Riverside, patients are all given the same low dose of buprenorphine — enough, Lepley says, to stave off withdrawal without encouraging "diversion."

That's when a patient saves a dose and gives it to another inmate — at Riverside, women divert largely to help friends through their own withdrawal. Only 10 women out of the 388 who have been treated since February have been pulled from the program for diverting their medication.

The main goal, Lepley said, is to keep people from dying when they leave prison.

Inmates are given a five-day prescription for buprenorphine when they leave Riverside, and are instructed to see a specially licensed physician to get more. Over the first 30 days of the program, about 40 percent filled it. But some of the rest may have been transferred to another facility, and had no opportunity to fill it.

In other cases, inmates' medical assistance is suspended while they're in prison, and doesn't immediately reactivate upon their release. Buprenorphine is an expensive drug, Lepley said, and many patients can't afford it without insurance. According to the GoodRX website, the retail price is around $300 for 30 doses of the brand-name drug; generics are a little cheaper.

Sometimes, Lepley said, the date on patient's buprenorphine prescriptions doesn't match their release date, and some pharmacists won't honor them.

"I hope that we can work out increasingly more effective 'warm handoffs' to programs in the community to mitigate the need for this bridge prescription. This is an evolving process," he wrote in an email.

Advocates say the program is a step in the right direction, though they balked at the idea of a standard dose of buprenorphine: "One size fits all approaches aren't helpful when people need tailored care or individualized care," said Sheila Vakharia, a policy manager in the office of academic engagement at the Drug Policy Alliance, which advocates for the decriminalization of drug offenses.

Still, she said, in the absence of robust drug treatment networks, the criminal justice system has become a catch-all for people struggling with addictions — and that prison systems must adapt to provide them their best shot at recovery.

>> READ MORE: Philly police are being trained to connect people in addiction to treatment, instead of arresting them.

"We need to see more innovation and creative strategies on the ground," Vakharia said. "We need more models — to show that, if Philadelphia can do it, someone else can, too."

At minimum, Lepley takes comfort from knowing that women who were on buprenorphine in prison are less likely to suffer a fatal overdose if they return to using street drugs.

"You heard about girls leaving out of here all the time and dying because their tolerance was so low," said a woman in her early 30s who has been in the program for a few months — a long stretch by Riverside standards.

As is the case in the men's facilities, inmates are also given a dose of naloxone, the overdose-reversing drug, on their release. The prison system alone has handed out about 10,000 kits since last summer; that's in addition to many more distributed to Philadelphia's non-prison population.

The inmate in Lepley's office who spoke of women dying soon after release received naloxone after her last stint at Riverside.

Days later, her own mother overdosed, and the daughter used the prison's naloxone to save her.