Lights, camera, cleanup for heroin camp … but then what?

After months of buildup, the cleanup of the encampment along the Conrail track begins on Monday. Experts warn the opioid crisis will not end.

Months of buildup — shocking images of needles and trash, disturbing stories of addicts overdosing before your eyes, Dr. Oz's announcement to the world that "I just walked into hell."

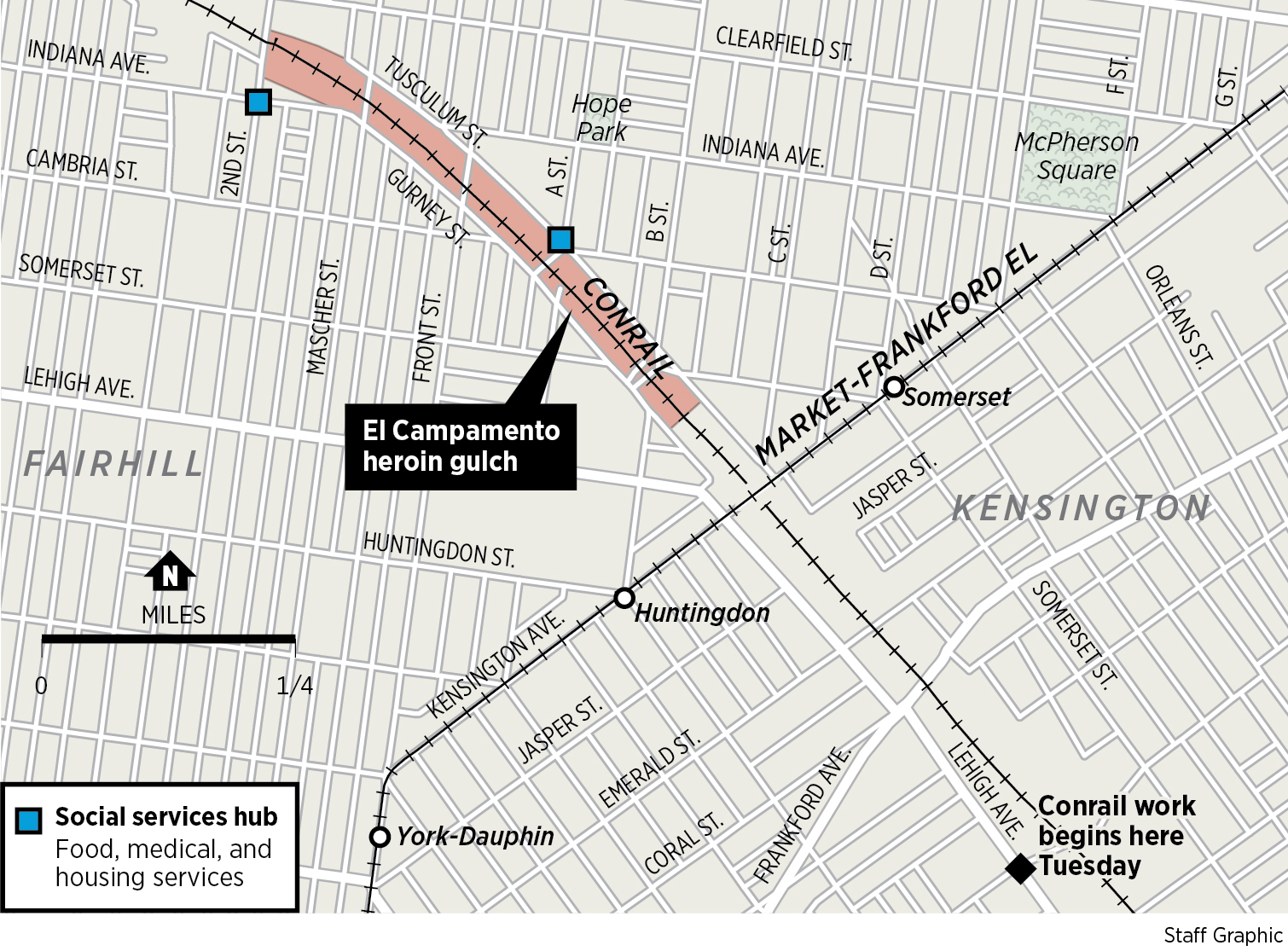

At the edge of Kensington, one of the city's hottest neighborhoods, the homeless heroin camp below Gurney Street that for weeks has been the epicenter of media attention in the nation's opioid crisis will be cleaned up and shut down.

The crisis won't be, experts warn, even locally.

Some worry that, once the media trucks pull away from what residents call "El Campamento," overdose fatalities will rise as users shoot up in abandoned houses with no one watching out for them.

"There is this expectation that fences are going to go up and lights are going to go up and it's problem solved," said Jose Benitez, executive director of Prevention Point Philadelphia, the health-care provider and needle-exchange that has worked with the community for years. "That is not the way it is going to happen."

No one really knows where the residents of the encampment along the Conrail tracks are going. Most have already left, some into treatment, several dozen to city-funded housing, others joining small homeless clusters under I-95, more likely breaking into abandoned houses nearby.

The far more numerous day visitors seem to be fanning out around the neighborhood, using in parks and anywhere there is shade. Some say that street-corner transactions have become even more brazen.

"When they close it, I'll try to go somewhere else," said a 53-year-old homeless heroin addict named Jeff, who told city behavioral health workers the other day that he was still pondering another try at treatment and was on a waiting list for temporary shelter. Then he scrambled up a steep embankment and disappeared into the underbrush, his small, ripped pack bulging with belongings and the overdose reversal medication he has used on others several times.

A drumbeat of trespassing summonses, waves of outreach workers, tours by reporters, and a letter from Conrail left no doubt about what was coming. Anticipation and anxiety grew as activity was rumored and then delayed.

A drumbeat of trespassing summonses, waves of outreach workers, tours by reporters, and a letter from Conrail left no doubt about what was coming. Anticipation and anxiety grew as activity was rumored and then delayed.

The July 31 contractual deadline that Philadelphia and railway officials agreed to last month has a ring of finality. But the process — preparing the site, planning possible futures for its occupants, building trust with a chronically homeless, drug-addicted community — is gradual.

Small areas of fencing have been going up for weeks. Heavy equipment capable of cutting brush and trees began moving to a rail yard with access to the tracks at Trenton and Lehigh last week. "I'm not sure there is going to be a whole lot of action on Monday," said Conrail spokeswoman Jocelyn Hill. She said the machinery actually will start work on Tuesday.

Hill said that the job would take several weeks but that there is no timetable. Piles of needles, mattresses, and assorted debris, both the detritus of homelessness and garbage dumped by pickup trucks, must be picked up. An area along the track will be cleared, a request from the Police Department to gain lines of sight.

Old-fashioned Reading Railroad wrought-iron fencing will be installed 6 feet high along varying topographical terrain, Hill said. "It is not easy to cut through. It is not easy to jump over. It is not easy to knock down."

Conrail's 1½ miles of fencing will meet up with fencing that the city is installing and repairing at the ends of its bridges over the tracks.

Police Inspector Ray Convery, who oversees the East Division, which includes the Kensington/Fairhill section, said his officers were primarily concerned with safety. "I don't want somebody sleeping in the weeds when the [machinery] comes in," he said. "We're not going to lock them all up for doing their drugs. We want to save them."

Neighborhood foot patrols were replaced a month ago by 24 bicycle officers in a pilot program that makes them more visible. All are new graduates of the police academy, who typically are "more reactive," Convery said, issuing summonses for trespassing where older officers might give warnings.

Others see public health and safety downsides.

"This will create a lot of tension, I think, between residents and people who are looking for a place to get high," said photographer Jeffrey Stockbridge, who immersed himself in the community for his website and book, Kensington Blues.

"The camp tends to manage itself," said Dan Martino, secretary of the Olde Richmond Civic Association, "despite the fact that it looks kind of disgusting."

Virtually everyone there carries the emergency overdose reversal medication naloxone, leading some advocates to predict an increase in fatal overdoses in abandoned houses — within a half mile of the Gurney Street gulch are more than 30 houses that the city deems uninhabitable — although others believe that most users will inject publicly or with buddies.

Just 17 of last year's 907 fatal overdoses in the city occurred at the encampment, according to the Medical Examiner's Office, a statistic that places Benitez among the worriers.

"You would think there would be a lot more, and it's because people know how to reverse, to take care of themselves," he said. Prevention Point has been supplying and training people in how to use the medication for years, long before opioids were seen as a mainstream crisis, and before providing the medication became the goal of states across the country with Govs. Christie and Wolf among the leading proponents.

The nonprofit's staff and volunteers are a major part of the city's outreach, but they are more focused on "trying to build long-term relationships" with users who are "not ready for treatment, and figuring out housing possibilities for them," Benitez said.

Other city-supported teams tend to focus on either housing or treatment, and fall into a mind-boggling array of bureaucratic divisions dictated by federal funding categories.

The results so far have been hard to quantify, said Liz Hersh, director of the city's Office of Homeless Services. Is a psych unit "housing"?

Measuring treatment is even harder. "We've engaged a lot of people," said Roland Lamb, deputy commissioner of the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services, who defined success as "engagement, and treatment eventually."

The city's presence will ramp up again on Monday. A "social services hub" will be established at Second and Indiana Streets. Assessments for treatment will be conducted in a trailer at Tusculum and A Streets.

No exodus is expected. Addicts can be desperate for help yet unable to take it, experts say.

"Nobody chooses to be an addict in Kensington," said Christine Simiriglia, president and CEO of Pathways to Housing PA, which is working with the city on an opioid initiative that starts with housing and sets no mandates for treatment.

"Trust me. Nobody says 'I want to grow up and be an addict in Kensington.' "