The opioid overdose crisis is hitting all of Philadelphia, new data show

The opioid epidemic, though less visible in places like South and West Philadelphia, is affecting the entire city at unprecedented rates.

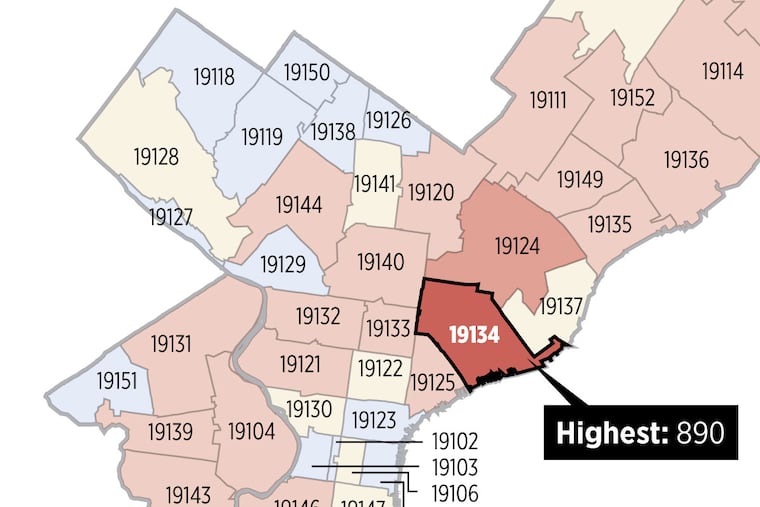

A new analysis of overdose deaths and where they occurred in Philadelphia over the last decade shows that although the Kensington area is by far the hardest hit, few corners of the city are untouched by an opioid crisis that usually kills in private homes, away from the open-air heroin encampments that have received so much attention.

Neighborhoods across the city saw alarming spikes in fatal overdoses, according to data from the Medical Examiner's Office that show that while the epidemic may be less visible in places like South and West Philadelphia, scores of people there are dying.

"It's too easy for people to say, 'That's not our problem.' But if they look close to home, everyone will find it is their problem," said Tom Farley, the city's health commissioner. "I'm alarmed by these numbers everywhere. It's really a devastating increase."

The 19134 zip code, which includes Kensington and Port Richmond, saw 209 overdose deaths in 2017, a 49.3 percent increase over the year before. Just north, the 19124 zip code (Frankford, Juniata Park, Crescentville) recorded a jump in fatal overdoses of 155.6 percent, from 36 in 2016 to 92 the following year.

>> READ MORE: A father and son, evicted from a heroin camp, move on in Kensington | Mike Newall

In the 19145 zip code (Point Breeze and South Philadelphia neighborhoods west of Broad Street), deaths increased by nearly 43 percent from 2016 to 2017. Across Broad, in the 19147 zip code (Bella Vista, Queen Village, and parts of East Passyunk) just nine people fatally overdosed in 2016. A year later, 22 people died of overdoses there — a 144.4 percent increase.

The scope and visibility of the crisis in Kensington — the open-air drug use, skyrocketing overdose rate, and large homeless encampments — have drawn intense attention locally and nationally.

A decade of overdose deaths

But about 75 percent of fatal overdoses in Philadelphia occur in private residences, largely away from public view.

"In South Philly, we don't have a Gurney Street" — the heroin camp in a train gulch in Fairhill that the city shut down last year, said Priya Mammen, the director of public health programs and a physician in the emergency department at Methodist Hospital-Jefferson Health. "We have day laborers, construction workers, people who have become habituated to opiates and have moved into the space of addiction. And they overdose before they go to work and on lunch breaks.

"There is no poster child for the epidemic."

Methodist's emergency room handles most of South Philadelphia's overdoses, and saw the third-highest volume of overdose patients in the city in 2016, Mammen said. Many have the homes and family support systems that those living in Kensington's camps lack. But they still are vulnerable to the effects of the stigma that keeps people from seeking treatment, Mammen said. Some of her patients in addiction assume that because they have jobs and homes, their addiction is manageable, even under control, she said.

>> READ MORE: 'My mind is spinning.' Philly sweeps aside 2 heroin camps in Kensington

One South Philadelphia patient Mammen treated turned to heroin after her doctor tried to wean her off opioid pain pills; she showed up at the Methodist ER after a botched injection.

"She had never shot up before, and she developed a skin infection," Mammen said. "And she was mortified — she said, 'I can't even look at you, I'm so embarrassed that I'm here for this.'"

Farley said the citywide overdose numbers show that fentanyl — the powerful synthetic opioid often used to cut heroin, and present in most overdose deaths last year — is being sold all around the city. "There are more potent drugs which make it far easier to die of an overdose," he said.

One potential bright spot: Overdoses decreased during the last quarter of 2017, and that trend seems to have held through the first quarter of this year, he said. Yet, the death rate is "still substantially higher than previous years," he said. And it's unclear what may have kept those numbers down: increased distribution of the overdose-reversing drug naloxone, more careful drug use among people in addiction, increased treatment, decreased opioid prescribing, or a change in the levels of fentanyl sold on the street all could be involved, Farley said.

>> READ MORE: Love in the time of opioids: Adoption connects drug-exposed kids with new families

"It's a crisis still, the numbers are staggering," he said. "But we're somewhat relieved to see it going in the right direction."

Mammen said it's crucial that the city tailor its approach around its neighborhoods. At a recent forum on the opioid crisis in her hospital's area, the main complaint she heard from neighbors was that the event hadn't been promoted enough.

"The culture of South Philly is very talkative — they're not shying away from it," she said. "There is a community that is engaged and not wanting to have their neighbors die. The return on investment of educating other parts of the city is huge — it's time to broaden the discussion."