Breast cancer caused by genetic mutation gets first approved treatment

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Friday approved the first treatment for advanced breast cancer caused by inherited mutations in BRCA genes. The agency initially approved AstraZeneca Pharmaceutical's Lynparza (olaparib tablets) in 2014 to treat advanced ovarian cancer caused by mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Friday approved the first treatment for advanced breast cancer caused by inherited mutations in BRCA genes.

The agency initially approved Lynparza (olaparib tablets) in 2014 to treat advanced ovarian cancer caused by mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2.

The expanded approval follows the model of "developing drugs that target the underlying genetic causes of cancer, often across cancer types," Richard Pazdur, director of the FDA's oncology center of excellence, said in a statement.

The FDA also approved a genetic test made by Myriad Genetics, BRCAAnalysis CDx, as a companion to Lynparza for identifying breast cancer patients with mutations.

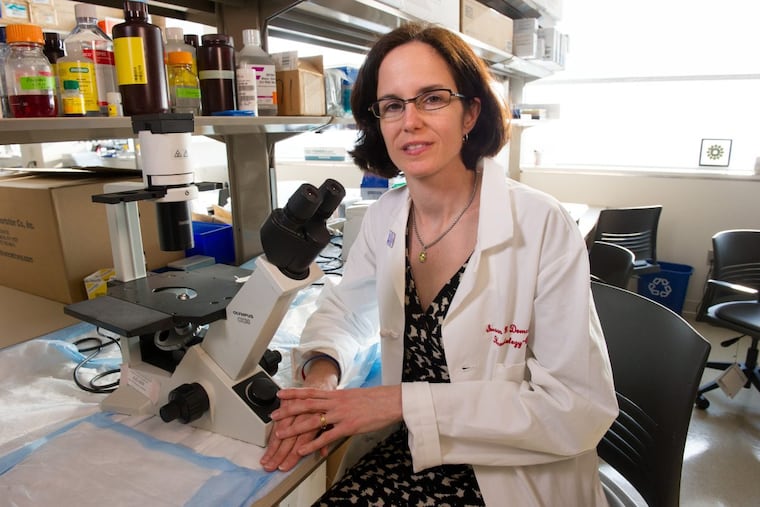

University of Pennsylvania oncologist Susan Domchek, a BRCA researcher who co-led the study behind the expanded approval, said it is also a significant advance for BRCA patients with an ultra-aggressive form of breast cancer known as "triple-negative." Until now, their only drug option was chemotherapy, with all its toxic effects.

"Fifty percent of the BRCA patients in this trial were triple negative," she said. "So all of a sudden, we have a new option for a subset of triple negative patients."

BRCA mutations interfere with DNA repair, making carriers predisposed to develop cancer. Of the 266,000 women who will be diagnosed with breast cancer and the 40,000 who will die of the disease this year, about 5 percent to 10 percent carry a mutation.

Lynparza, which costs about $13,000 a month, belongs to a new class of drugs called PARP inhibitors that exploit the complex role of DNA repair in malignancy. The drug blocks an enzyme involved in repair, further crippling cancerous BRCA cells, and leading to a slow-down of tumor growth or even cell death.

Lynparza was not effective for all BRCA patients, although the response rate was high. In the trial of 300 advanced breast cancer patients that compared Lynparza to chemotherapy, about 60 percent on Lynparza saw an effect, compared to 29 percent on chemo. Lynparza patients' tumors did not grow, a measure called progression-free survival, for a median of 7 months, compared to 4.2 months for the chemo group.

Severe side effects occurred in 37 percent of Lynparza patients, compared to 51 percent of those on standard therapy.

Domchek said researchers hope to see higher and longer rates of response to Lynparza among earlier-stage patients because they have received fewer treatments and their cancer has developed less resistance. Trials are now testing whether giving Lynparza to BRCA patients right after initial surgery and chemotherapy can prevent recurrence. It is also being tested in combination with other targeted therapies and with new immune-boosting drugs.

Lynparza is marketed by AstraZeneca and Merck. In a press release, the companies said they are "working together to deliver Lynparza as quickly as possible to more patients across multiple settings, including breast, ovarian, prostate and pancreatic cancers."