Bucks dog travels to France for $50K heart surgery not available in the U.S.

"In the United States, the disease in dogs is not cured with the current medical treatment."

Jeanne Navratil knew that Cavalier King Charles spaniels were prone to heart disease. So when her 3-year-old dog, Sophie, began to slow down and sleep more in 2011, she made an appointment with her veterinarian. They discovered a mild heart murmur — an early warning sign of a deadly heart disease in dogs.

Six years later, she was diagnosed with mitral valve endocardiosis. And after a trip to France in November for open-heart surgery performed by a team from Japan, the bright-eyed pup with the sweet disposition is almost as good as new.

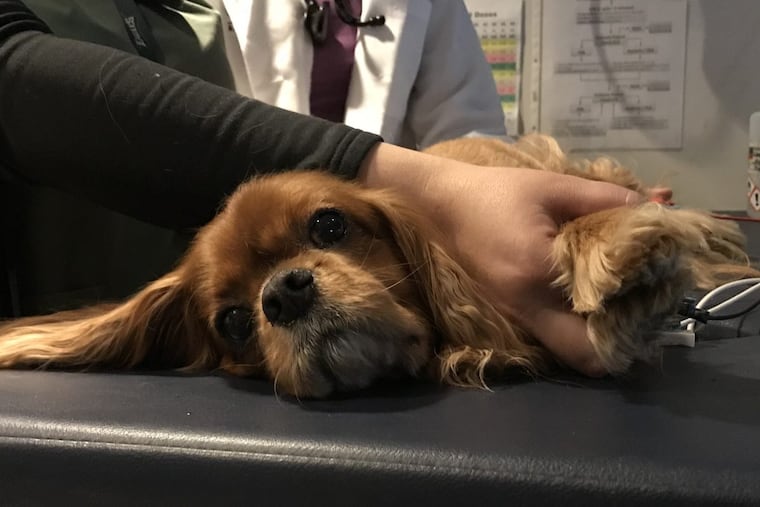

"She's my baby," said Navratil, of Washington Crossing, during a recent follow-up appointment at the Veterinary Specialty and Emergency Center (VSEC) in Levittown, Bucks County, where Sophie is a patient. "I could not accept that this was a long-term death sentence for her."

In the general population of dogs, the prevalence and severity of mitral valve disease increases with age, said Beth Bossbaly, a board-certified veterinary cardiologist at VSEC, and Sophie's doctor. It is mostly a disease of small-breed dogs, however, and by age 10, about 30 percent of breeds such as poodles, Pekingese, Pomeranians and Chihuahuas will have mitral valve disease, she said

"In Cavalier King Charles spaniels, the disease is overrepresented," Bossbaly said. "By the time they are 10 years old, I believe, 60 percent will have a heart murmur."

The mitral valve helps regulate blood flow from one heart chamber to another. When the valve is damaged, blood flows backward, depriving the chamber where it should be going. Over time, the disease can weaken the heart muscle, leading to congestive heart failure.

Sophie was initially treated in 2012 with drugs and monitored closely because the disease was progressing so rapidly. She was stable until November 2015 when her murmur became louder and she was switched to another drug. Eight months later, her valve began to deteriorate. By March 2017, she developed pulmonary hypertension, or high blood pressure in her lungs, said Bossbaly. Sophie was headed for congestive heart failure.

"I just couldn't take that answer that there is nothing you can do," said Navratil, a retired product manager at a bank. "There just had to be something."

Mitral valve repairs are made on people all the time. But there is no cure available in the United States for canine mitral valve disease, said Bossbaly. "At some point the disease gets ahead of us."

PennVet is not currently offering open-heart surgery for mitral valve repair, said Mark A. Oyama, professor and chief of cardiology at the School of Veterinary Medicine.

At the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine at Virginia Tech, a team has begun to explore options for a less expensive and less invasive treatment, said Mindy Quigley, clinical trials coordinator.

Although the disease is not rare, the current treatment is so complex and prohibitively expensive that only a few places in the world are willing to perform that type of surgery, said Quigley.

The Virginia Tech team is exploring a procedure that could be done on a beating heart involving "a series of knots and cords that mimics heart tendons and creates a synthetic anchor to help the mitral valve do its job," said Quigley.

The University of Florida Small Animal Hospital in Gainesville hopes to start an open heart surgery program in 2018, said Simon Swift, clinical associate professor of cardiology at the school.

"We desperately need this here," said Swift. The procedure requires the use of a bypass machine and the right combination of people on the team, including anesthetists, perfusionists, and emergency critical-care staff to continually monitor the dogs after surgery for an extended period, he said. Swift said nearby UF Health Shands Children's Hospital has offered help and expertise.

"This is not a procedure you can do once every six months," Swift said. The mitral valve procedure would form the basis of the open-heart program and allow them to do other procedures. "You will never be busy enough if all you are doing is the odd congenital repair."

There is, however, help available outside the U.S.

Japanese veterinary surgeon Masami Uechi, of the JASMINE Veterinary Cardiovascular Medical Center in Yokohama, has a 90 percent success rate with an open-heart procedure to repair the valve. He and his team regularly travel to the Clinique Veterinaire Bozon in Versailles, France, to operate on dogs.

Navratil saw a posting on Instagram about the Mighty Hearts Project, a group of dog owners who have taken their dogs outside the country for treatment.

"We are basically all people that had the surgery" performed on their dogs, said Nathan Estes, who helped found Mighty Hearts. He took his dog Zoey to France for the procedure. He estimates about 50 people have contacted him and proceeded with the surgery.

The hefty price tag – about $50,000 – can put the procedure out of reach for most dog owners. Estes took out a loan to cover it, but said he's known people to run up their credit cards or skip vacations for years to cover what equates to a nice car, numerous vacations, or a year in college. It's worth it, he said, considering how important his dog is to his family.

The cost to have the surgery in Japan averages $25,000 but there is a 15-hour flight. Plus, dogs have to be quarantined for six months at home before they can get into Japan — too long for a sick dog to wait, Estes said

Navratil and her ex-husband, Kurt Fuoti of Long Valley, N.J., decided to share the cost for the surgery in France. Pet insurance covered some of the U.S. vet bills prior to and after the surgery, she said.

The logistics for travel to France were daunting, so Navratil turned to Mighty Hearts for assistance.

A USDA-certified veterinarian must sign off on the trip, owners must produce rabies certificates and ensure their dog has a microchip. There are also the airline reservations, pet-friendly accommodations, and taxis that must be set up in advance, Estes said.

Navratil said she had Sophie certified as an emotional support dog so she would be able to travel in the airplane's cabin. On the way home, the dog needed to walk in the aisles for three minutes every two hours to prevent blood clots from developing. She also bought a dog stroller for 18-pound Sophie so she didn't have to carry her.

"You could never put them in cargo," she said, adding United Airlines, and especially its flight attendants, were "wonderful" during her trip. (And it should be noted that Sophie demonstrated during a recent visit from a reporter that she is an exceptionally well-behaved dog.)

Sophie's treatment was not without complications.

The dog needed two transfusions during surgery. She also developed a urinary-tract infection and three blood clots and was placed on heavy-duty antibiotics and blood thinners. Her time in France was extended an extra week, said Navratil.

Following the surgery, there is a very strict three-month recovery program to give the heart time to heal, said Navratil. There would be no jumping or dog parks. Getting on or off furniture required assistance. Navratil's house is now filled with baby gates, and she has disconnected her doorbell so it doesn't startle Sophie and send her heart rate soaring, she said.

Now, almost two months into her recovery, Sophie is starting to pick up, said Navratil. She sleeps less, shows more interest in her toys, and takes longer walks.

Last week, during an echocardiogram at VSEC, Bossbaly reported that two of the blood clots were no longer visible.

"It's an improvement," said Navratil. "We are going in the right direction."

Sophie's tongue, once a pale lavender, is now back to bright pink. Where once Navratil could feel every strained beat of Sophie's heart, now there is nothing out of the ordinary, she added.

"Her quality of life is pretty darn good," she said.