Electroconvulsive therapy makes financial sense for some depression patients, study says

The University of Michigan research found that for patients getting treatment for the first time, medication or talk therapy were more cost-effective than ECT. But for patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT was a more cost-effective and often successful option.

Gina Deney has been battling severe depression since she was a child. She has been hospitalized three times — once after a suicide attempt — and has tried more than 25 antidepressants that either had intolerable side effects or were ineffective.

"I've been through the gamut," said Deney, a feisty 55-year-old who now lives in Wilmington.

Deney has treatment-resistant depression — when a patient's symptoms aren't alleviated after trying at least two different antidepressants — and bipolar disorder. As a last-ditch effort, she turned to electroconvulsive therapy in 2015, first at Kennedy University Hospital in Cherry Hill and then at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. ECT causes small seizures that are electrically produced — stimulating areas of the brain associated with depression — with the aim of relieving various forms of mental illness.

ECT has alleviated her depression and stabilized her, Deney said, allowing her to get back to work running her home-care agency. Overall, remission with ECT is reported in about 80 percent of patients, according to the American Psychiatric Association, compared to about a 28 percent remission rate with an antidepressant.

But many people believe ECT to be a violent treatment. The stigma is partly based on such movies as One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and books like The Snake Pit, in which the narrator paints a horrifying vision of ECT: "Now, the woman was putting clamps on your head … and here came another one, another nurse-garbed woman, and she leaned on your feet as if in a minute you might rise up from the table and strike the ceiling."

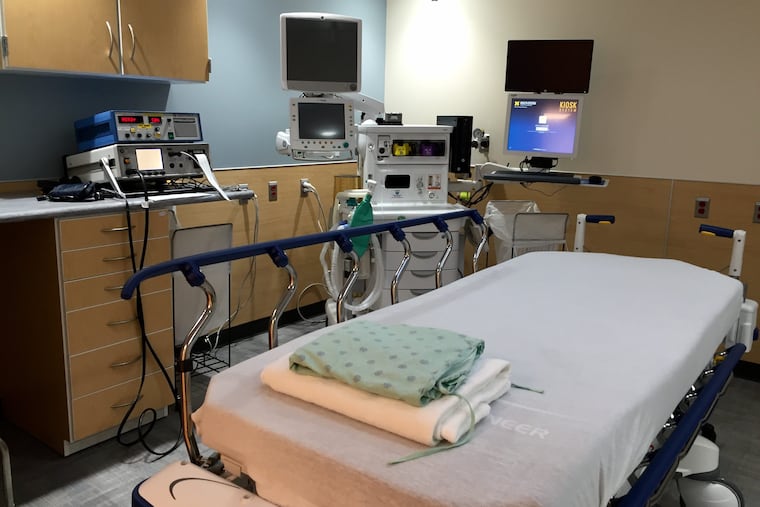

Today, however, ECT works very differently from when The Snake Pit was published in 1946. It uses far milder electrical pulses than it did decades ago, and the anesthesia is short-term. Patients are put to sleep for three to five minutes and given muscle relaxers to prevent injury. Then their brains are stimulated for a few seconds, causing seizures. When the patients wake up and regain their bearings, they go to a recovery room until they feel well enough to go home. Patients cannot drive after ECT.

Stigma against ECT persists nonetheless, as well as the popular notion of it as a treatment of last resort. So it's surprising that a study out of the University of Michigan, published in JAMA Psychiatry, suggests that trying ECT after just two other failed treatments — such as antidepressants or therapy or some combination of the two — makes financial sense.

The study found that for patients getting treatment for the first time, medication or talk therapy were more cost-effective than ECT. But for patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT was a more cost-effective and often successful option. Not to mention that waiting for an antidepressant to kick in over a period of weeks can be dangerous for those who are severely depressed and may be suicidal. ECT works much faster.

The study may reshape physicians' notions about ECT and open up additional treatment options for patients with treatment-resistant depression, which affects 12 percent to 20 percent of all depressed people, according to a 2014 study.

"I think the big message is really not that [ECT] has to be done, or that you should do it after two other medication failures, but [that] it may not be unreasonable especially if your symptoms are severe," said senior author of the study Daniel Maixner, associate professor of psychiatry at Michigan. "The longer a depression lasts, the higher the number of medication failures you have, the tougher" it is to treat. That creates a pressure to move to ECT sooner rather than later.

The University of Michigan team examined well-regarded studies to create a simulation of what it would look like for patients to travel through various treatment options. The study incorporated a mathematical model that used an algorithm to run through hundreds of treatment scenarios.

"You're trying to simulate what would be possible routes for typical patients," Maixner said.

The study predicts that ECT as a third line of treatment would have an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $54,000 per quality-adjusted life year. (The ratio measures the value received for dollars spent to restore a patient's quality of life.) That is much lower than the $100,000 threshold usually considered worthwhile for health spending. Deney's treatment costs about $3,000 a session, which she pays for up front. Insurance reimburses her about $900 a session.

So the question is: Who would choose ECT and what doctor would recommend it after just two failed treatments?

"It's a terrifying process," said Deney, who went through more than 50 sessions of ECT between April 2015 and November 2017. A typical course of ECT runs three times a week for four to six weeks. Deney's treatment has far exceeded that because of the severity of her symptoms.

"You're not going in to have somebody put stitches in your arm. You're doing something with your actual brain. And when you really start to ask questions about what it's doing –— we don't know," she said.

Deney has lost a significant amount of long-term memory and struggled with some cognitive deficits that she ultimately regained. Although the risk of loss of memory and cognitive ability exists, it is not as prominent as it was decades ago, when doctors administered higher doses of current. But because Deney has had such strong side effects from the treatment, she has taken a break from ECT for a while, maintaining her mental health through medication and therapy. Eventually, she will return to ECT, at least for maintenance sessions, she said.

Michael Thase, psychiatry professor at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, said ECT puts a lot of "wear and tear" on the patient, who has to go to the hospital two to three times a week for several weeks during the acute phase of treatment.

"If you're having the treatment, you really can't work," Thase said. "And if it works, you want to be darn sure you don't relapse" by sliding back into a debilitating depression.

Half the people who benefit from ECT are sick again in six months, Thase said, so most doctors help patients come up with a maintenance plan that may include medication as well as less frequent ECT sessions.

Ultimately, however, ECT is "the most effective treatment in psychiatry and the most effective treatment for suicide," said John Worthington, who conducted thousands of sessions on hundreds of patients over the course of several decades when he was at Abington Hospital. "ECT outperforms anything compared to it."

Deney knows, after all her years of failed treatments, that she needs ECT — despite that it continues to frighten her.

"It wasn't embarrassing. It wasn't humiliating. It wasn't any of those other words. It was purely terrifying," Deney said. "But I would've been dead had I not tried it. I have no doubt in my mind."