What diabetic mice can teach us about keeping teeth healthy

A new Penn study shows that unmanaged diabetes changes bacteria in the mouth. That means more inflammation of the gums - and even bone loss.

Along with all the other consequences of poorly managed diabetes, patients who don't or can't control their sugars are more likely to lose their teeth because of severe periodontitis, an irreversible gum disease that attacks the tissues and bone around the teeth.

The connection has long been known. But exactly why it happens hasn't been so well-understood.

Now, a new study by University of Pennsylvania researchers that was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research shows that unmanaged diabetes changes bacteria in the mouth so that microbes are more capable of causing disease. That means more inflammation of the gums and bone loss.

The findings on the oral microbiome, researchers hope, will help lead to better dental treatments for people with diabetes — and anyone with periodontitis.

"Studies done on the microbiome had been quite limited," says Dana Graves, a professor of periodontics at Penn Dental Medicine and senior author of the study.

"Rather than only looking at the bacteria present, for the first time we examined the destructiveness of the bacteria by transferring them from a diabetic mouse to a normal germfree mouse," he said. "We found that the bacteria from a diabetic animal created more inflammation and more bone loss than bacteria from normal mice."

About 47 percent of Americans ages 30 and older and more than 70 percent of adults 65 and older have some form of periodontal disease, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The most common is gingivitis, which causes bleeding of the gums and inflammation, but not irreversible loss of bone around the teeth. With proper dental hygiene, gingivitis is reversible.

Periodontitis — an irreversible condition — is much less common, affecting 15 percent to 30 percent of dental patients with gum disease and causing damage to soft tissues and destroying the bone that supports the teeth. People with poorly managed diabetes are about three times more likely to have this form of the disease.

"In poorly controlled diabetes, there is greater inflammation of the gums," says Graves. "You have a cycle where diabetes causes inflammation that changes the bacteria in the mouth, which causes more inflammation, which makes people with diabetes have a higher risk of periodontal disease."

In the study, Penn researchers compared the oral microbiome of healthy mice with animals with diabetes. They found that the two groups had similar profiles before the diabetic mice developed hyperglycemia — or high blood sugar levels. With high blood sugars, the oral microbiome of the diabetic mice shifted, forming a less diverse and more disease-causing community of bacteria.

"The diabetic mice developed periodontitis, a loss of bone supporting the teeth, when the blood sugar levels rose," says Graves.

The next step was to uncover whether the microbial changes were responsible for the disease. Researchers tested this by transferring microbes from a diabetic mouse to a nondiabetic mouse. They found that the transferred bacteria of the diabetic animal created more inflammation and more bone loss in the normal mouse.

"If you transfer normal bacteria from one mouse to another, it will create some bone loss," says Graves. "But in this case, the normal mice who received microbes from the diabetic mice showed significantly more bone loss [42 percent] than mice who had received a microbial transfer from normal mice."

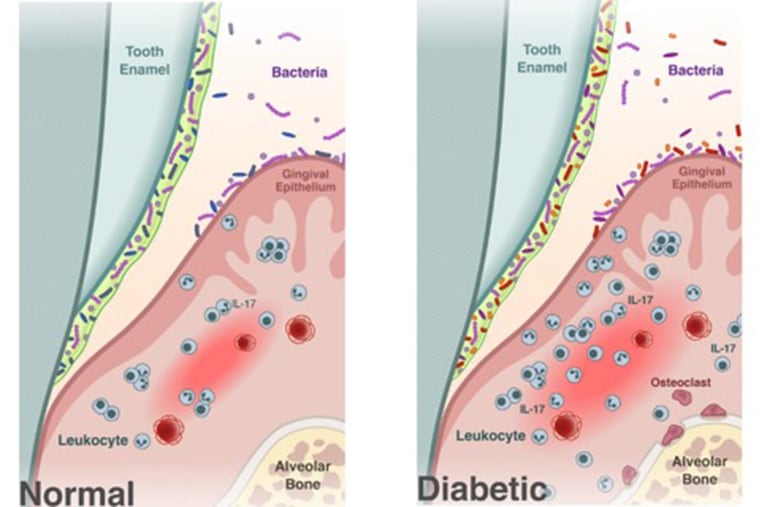

The researchers also found that certain inflammatory markers — particularly IL-17, a signaling molecule important in immune response and inflammation — were increased in diabetic animals. Higher levels of IL-17 in humans are associated with periodontal disease.

"We thought if we blocked IL-17, it might prevent changes in the bacteria," says Graves. "After injecting an antibody to IL-17 directly into the gums of the mice, we examined the bacteria and found that its composition had changed less and that it made the bacteria less pathogenic, proof that the greater inflammation associated with diabetes led to a change of the bacteria."

While injecting an antibody into the gums is not an option for humans, "it suggests that if you can control inflammation, you could reduce the susceptibility of diabetics to periodontal disease. We need a way to target it a little more carefully," says Graves.

"This article," said Renate Lux, professor of periodontics at the UCLA School of Dentistry, "provides new and important understanding of the interplay between the microbiome and the host in patients with diabetes." Lux was not associated with the study.

In the future, Graves' group hopes to explore whether changes observed in mice also occur in humans.

One takeaway from the study is the importance of rigorous oral hygiene for people with diabetes.

"It's very important that patients with diabetes and periodontal disease keep both their physicians and periodontists informed of changes in either condition," says Terrence J. Griffin, president of the American Academy of Periodontology. "People with diabetes should consider a regular oral hygiene routine, which includes brushing twice a day, flossing regularly, and checking in with a periodontist at least once a year or if they notice changes in their gums or teeth."

"Periodontal disease is largely preventable," said Graves. "If a person maintains good oral hygiene and good glycemic control — with a hemoglobin A1c level of under 7 — they will have less likelihood of developing periodontitis."