Influenza’s dangers, past and present

The deaths of 80,000 Americans from a particularly deadly strain of influenza last year is a reminder that the flu continues to be a threat, but one that can now be tamed with vaccines.

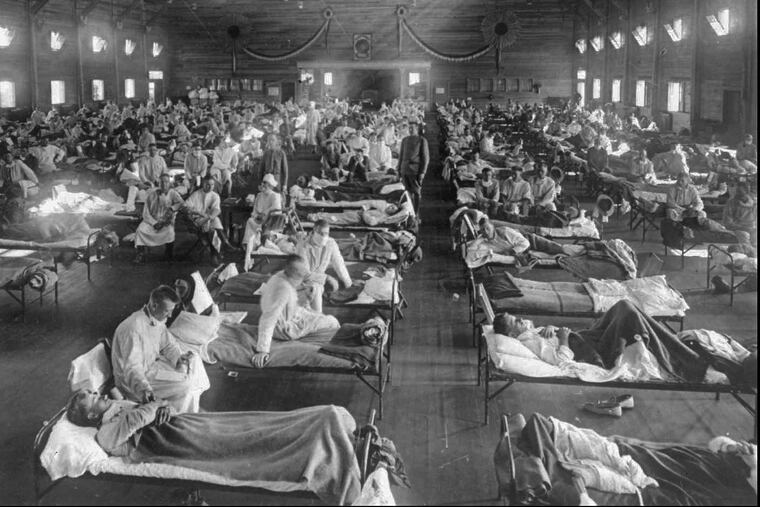

This year marks the centenary of the 1918 flu pandemic that took an estimated 50 million lives worldwide and led to 650,000 deaths in the United States. Much has been published about influenza and its impact, then and now. Locally, the Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania has been tweeting (@Penn_Bateshx) and posting on Facebook histories that highlight the work of nurses facing the deadly epidemic. Last year's deaths of 80,000 Americans from a particularly deadly strain of influenza is a reminder that the flu continues to be a threat, but one that can now be tamed with vaccines developed annually to protect from the newest strains of the disease.

Historical accounts of the flu, as well as warnings to get the vaccine, remind us of dangers past and present, but they often lack the power of personal narratives that bring us breathtakingly close to the experience of influenza.

One narrative that succeeds in describing what it felt like to have the flu can be found in a series of letters written by a young corporal, Alton W. Miller, at a base hospital at Camp Zachary Taylor in Louisville, Ky., in October 1918. They are housed in a scrapbook at the UCLA Biomedical Library Special Collections.

In one of his letters, the corporal informed his family that he'd been ill. "It takes the life right out of you," he wrote. Despite this, he told them, he would not report it to his superiors for fear of being sent to the camp hospital. He had evidently learned from others that "it is so overcrowded you don't get enough to eat and it is very dirty." At the time he wrote, the camp had 10,000 cases, and in another letter he reported, "The ambulances are running in every direction."

What did the flu feel like in 1918? The corporal listed the symptoms in another letter:

Severe pain in the head, and temples throb.

Dizziness

Pain in back from kidneys to shoulders

Sore throat and a cold in lungs

Sometimes sick in stomach

Absolutely no ambition

Corporal Miller's recitation echoed accounts in the medical literature, which described two types of symptoms. One of them was said to be comprised of "constitutional reactions of an acute febrile disease — headache, general aching, chills, fever, malaise, prostration, anorexia, nausea or vomiting," while a second consisted largely of respiratory complaints. The corporal hoped the worst was over for him and thought he was improving, unlike others around him. He wrote, with an acute sense of what took the lives of so many, that "they say you either get better or you get pneumonia very quickly." Then, as today, pneumonia was the most serious and deadly consequence of the illness.

Despite his initial optimism and his hope for both an American victory in World War I and a chance to prove himself on the battlefield, the corporal saw neither. Shortly after writing, "I would like to see the war end but I would also like to get to France," Miller was taken to the hospital. A friend of his kept the family back home in upstate New York apprised of his condition, as did the hospital chaplain, who wrote to suggest the family come to see him. During the outbreak, parents rushed to military camps to be with their ailing and dying sons. The military provided relatives visiting hospitalized kin with masks, and it paid for transportation back home for family members returning bodies for burial.

In this instance, unfortunately, the family did not arrive, and they learned of the corporal's death in a telegram and then from a letter describing his final days and hours. He was one of the approximately 43,000 men in uniform to die during the influenza outbreak. His death came shortly before the war ended.

Military members lived in close quarters, traveled in large groups in crowded troop ships and trains, and received bedside care in cramped, sometimes makeshift, hospitals.Those conditions helped spread the disease. Treatments were primitive in 1918 and not very effective. In the corporal's case, they consisted of blood transfusions and transfusions of a serum produced from the blood of convalescent patients (checked first for a Wassermann reaction indicating an infection with syphilis).

Today, those stricken with seasonal flu can be treated with antiviral drugs and, should the illness lead to bacterial pneumonia, with antibiotics. More importantly, though we may be working in crowded offices, sending children to crowded classrooms, and commuting on crowded trains, trolleys and buses, we have access to a preventive vaccine.

Residents of Philadelphia with health insurance can go to the pharmacy for a shot. Those without health insurance can visit community flu clinics or health centers for free shots. The city's website has information on health centers that administer flu shots.

Janet Golden, Ph.D., is professor emerita in the History Department at Rutgers University-Camden.