Pediatrician studies social, economic roots of kids' health issues

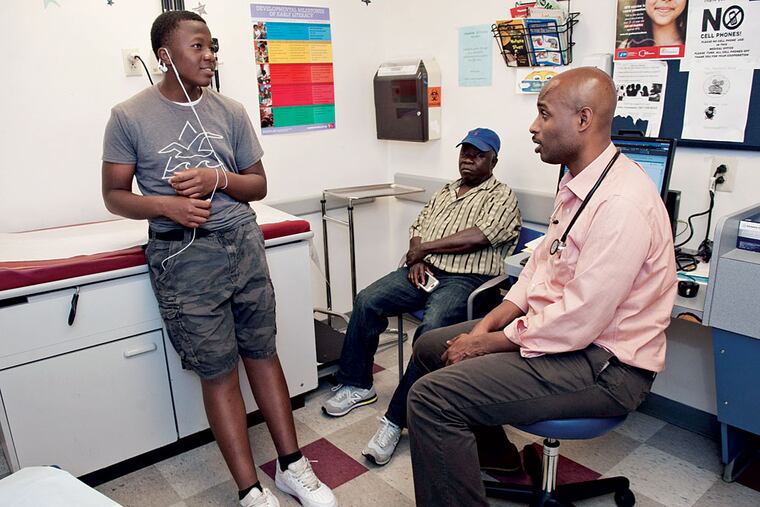

As a pediatrician at the Cobbs Creek Primary Care Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Roy Wade Jr. employs the usual tools of his trade, such as thermometer, tongue depressor, and stethoscope.

As a pediatrician at the Cobbs Creek Primary Care Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Roy Wade Jr. employs the usual tools of his trade, such as thermometer, tongue depressor, and stethoscope.

But as a researcher, he is working to develop a different kind of tool kit: a questionnaire to help pediatricians figure out which of their young patients are at greatest risk to develop early cognitive, emotional, and health problems.

Wade's work builds on the landmark 1998 ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) study that showed that the more traumatic events a person experienced in childhood, the worse their health would be in later life.

Generally, the higher the ACEs score, the higher the chances for substance abuse, mental illness, diabetes, cancer - as well as for dropping out of school and living in poverty.

Wade's research is finding that childhood exposure to violence, crime, and racism - all common for many of his economically disadvantaged patients - also takes a powerful toll on their health as they grow up.

"When we think about what is killing people, we think about structural problems - do they have insurance, do they have a primary-care provider, do they have a nearby hospital, can they fill prescriptions?" said Wade, 42. "But we don't tend to think about how social factors can attribute to health factors or morbidity."

Wade, who has a medical degree from the University of Virginia and a master's degree in public health from Harvard, has a three-year fellowship from the Stoneleigh Foundation, which works to improve outcomes for vulnerable children and youth. He says it's not enough for physicians to be aware of their patients' struggles; they also must have ways to communicate them to a larger audience.

"It's revolutionary how these factors early in childhood can affect health throughout a person's life," he said. "All of my colleagues care about these social issues, and many ask these questions of their patients. But we don't have a systematic way to document these experiences and convey the information to the power brokers."

The first ACE study relied on experts and researchers to develop the questionnaire. Wade is enlisting the help of youths themselves.

In a paper published last summer in the journal Pediatrics, Wade and his colleagues interviewed 119 adults 18 to 26 who grew up in Philadelphia, most in extreme poverty.

The study teamed with 12 organizations in seven geographic regions of Philadelphia, including homeless youth shelters, after-school and mentoring programs, health clinics, and community development corporations. Participants in 19 focus groups were asked to list adverse childhood experiences - events that were emotionally difficult to deal with and caused stress - then to select their top five out of the list.

Though a number of the subjects' answers overlapped with the original ACE study, several stressors were new - including single-parent homes, neighborhood crime, community violence, death, and discrimination.

Capturing the language of the participants is also important, Wade said.

"What we know," he said, "is that people become more engaged if the question and the wording resonate with them. . . . It also increases the validity of their response."

As the teenage son of a Baptist minister in Atlanta, Wade shadowed his father as he visited poor sick and shut-in church members unable to attend services.

Although the young Wade had no idea about health disparities, he remembered being "surprised by the number of younger members who had diabetes and were losing limbs or had cardiovascular disease."

Long before beginning medical training, "I began to wonder if there was a connection between poverty and health."

In honor of his accomplishments in this area, Wade was recently given the Embracing the Legacy Award by the Robert F. Kennedy Children's Action Corps.

"His research has helped us understand that if we understand the trauma, then we understand the behavior, which helps the intervention," said Edward Kelley, president and CEO of the organization. "It's a wonderful example of research going directly to practice."

Most people complain of stress from time to time, but for children, it can literally be life-changing.

"Research shows stress can affect brain development in a child," said Wade. "Unmitigated stress can affect the amygdala, which in turn can affect the flight-or-fight response, which can go awry in response to stressful situations."

Early stressful experiences can also damage executive-function skills, including "how you plan your day, how you can - or can't - rein in your emotions," he said.

"As a pediatrician, I know trauma and traumatic experiences are important in predicting health outcomes for my kids," Wade said. "I need to identify the problems and provide solutions. I don't know if my role is to fix the problems, but because we might be the only agency or association seeing kids consistently, we often can address a problem by facilitating a connection to a community resource. The tool kit can help us move upstream."

Wade, who is in the second year of the grant, anticipates the tool kit's being used not only in primary-care practices, but also broadly across agencies interested in child welfare.

"My hope is that ACE will eventually be a common currency, a language we will use to convey needs around trauma," he said.

"My goal is to think of health broadly. I became a doctor to help people flourish. I see children who are healthy, with no chronic illness, their vaccinations are up to date, but because of social factors, we don't get enough out of that kid.

"I don't think we should live in a world where your parents' income determines how you will live."

215-470-2998