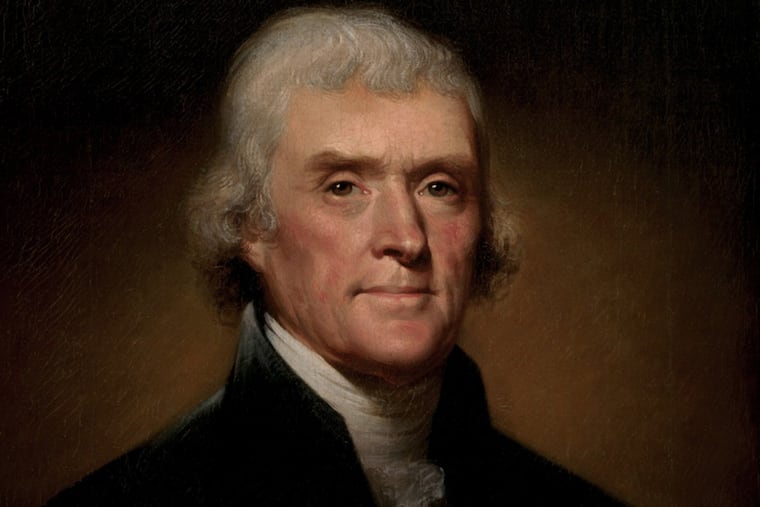

Medical Mystery: Thomas Jefferson's aching head

From age 19, our third president and principal author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, suffered from prolonged, incapacitating headaches. Frequently lasting for weeks, they usually came on when he was under stress, and were complicated by bouts of indecision, self-recrimination and buried rage.

From age 19, our third president and principal author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, suffered from prolonged, incapacitating headaches. Frequently lasting for weeks, they usually came on when he was under stress, and were complicated by bouts of indecision, self-recrimination, and buried rage.

For instance, at age 20, in March 1764, he had a violent headache for two days after behaving awkwardly in front of a girl he fancied.

After his mother's death in March 1776, he suffered headaches for six weeks. In 1782, he lost his wife of 10 years, Martha. Grief stricken and head pounding, he walked until he was exhausted, and sought relief in long horseback rides on secluded roads around his beloved Virginia estate, Monticello.

Jefferson had another six weeks of headaches after arriving in Paris as President Washington's minister to France in 1784, taking over for Benjamin Franklin. Some attributed his headaches to the stress of his role; others thought they were associated with romance. The 45-year-old widower had fallen in love with Maria Cosway, 27, an English-Italian artist and musician/composer. Jefferson learned that Cosway was married, and she suddenly returned to London at her husband's insistence. Jefferson's headaches worsened, but the couple maintained their correspondence throughout his terms as secretary of state, vice president and president, until his death in 1826.

Back in America to serve as Washington's secretary of state starting in 1790, Jefferson suffered from repeated headaches, presumably brought on by the many stresses of creating a new nation.

Jefferson was among those who favored states' rights and a limited role for the new federal government. Federalists, including Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, wanted to have the federal government assume the states' war debts — something that Jefferson, James Madison and other "Republicans" feared would lead the nation in the wrong direction. The Compromise of 1790 granted Hamilton's debt proposal, while moving the nation's capitol south from Philadelphia, as Jefferson and Hamilton wanted, to the shores of the Potomac River.

But Jefferson continued to be alarmed by the political rivalries he saw forming between Federalists and Republicans. In May 1792, Jefferson urged Washington to run for reelection, seeing him as the best hope for unifying the factions.

In December 1793, Jefferson infuriated Washington when he resigned his Cabinet position and returned to Monticello, saying he wanted to resume private life. But his political life and his headaches were far from over.

Jefferson ran for the presidency in 1796, narrowly losing the electoral college vote to Federalist John Adams. Due to a mistake in voting for Adams' running mate, Jefferson became his rival's vice president.

At his own inauguration as president in 1801 – after a bitterly contested election – Jefferson again called for unity.

"We have been called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists," he said.

Solution

The source of Jefferson's headaches has long been a source of debate for physicians and historians, who have alternately proposed that they were migraines, tension headaches or even cluster headaches. One medical historian concluded he suffered from a form of cluster headaches with a tension component, as the solace of horseback riding offered relief for this pain, as well as for depression and even dysentery.

Retiring from public life also seems to have helped. At age 75 Jefferson wrote: "A periodical headache has afflicted me occasionally, once perhaps in six to eight years for two to three weeks at a time, which seems now to have left me."

Cluster headaches are a series of frequent, short, extremely painful headaches occurring daily for weeks to months. In some patients, they may occur seasonally, and may be associated with allergies or even cyclical business stress.

Age of onset usually is under 30, they occur in men more than women, and they are thought to originate in a deep part of the brain such as the hypothalamus. Among other functions, this region serves as the body's "internal biological clock," controlling sleep and wake cycles. The pain impulses travel via the trigeminal nerve to the face on either the left or right side.

Contemporaries found Jefferson difficult to know, borne out by letters and notes, a man alternately strong and frail, convivial and reclusive, extraordinary and ordinary with a disappointing romantic life. Headaches may have been a somatic complaint in a man plagued by emotional crises and uncertainties suffering from periodic bouts of dejection and despair.

However, they did not shorten his life.

In June 1826, at age 83, Jefferson was confined to bed. He fell into a coma on July 2, 1826. On July 3 he awakened and asked, "Is it the fourth?" He died 50 minutes into the next day, July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Allan B. Schwartz, M.D., is a professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology & Hypertension at Drexel University College of Medicine.