Mutter exhibit recalls how the sacrifices of black Civil War troops advanced medicine

Struck down by disease far more frequently than their white comrades, with nearly double the death rate, black soldiers who joined the U.S. Colored Troops would prove pivotal to medicine's understanding of the greatest public health crisis in the young nation's history.

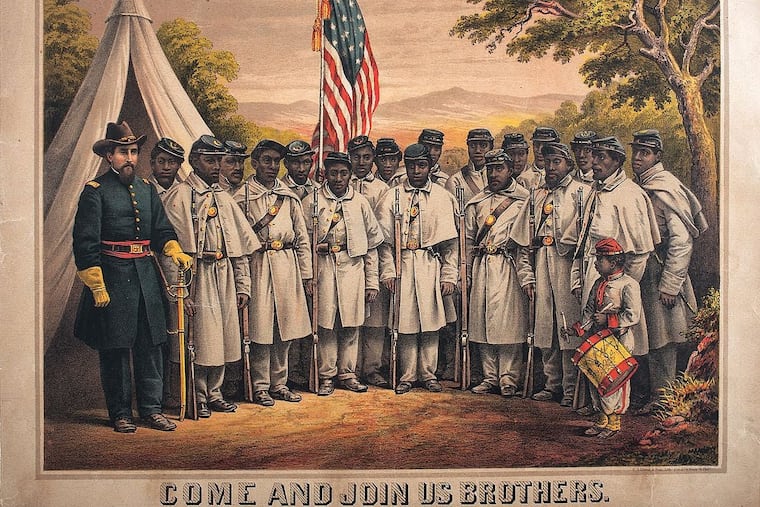

The Civil War marked both the emancipation of enslaved African Americans and the first time black men, some recently liberated from the South, others who had long been free in the North, were recruited to serve in the U.S. military. But these soldiers — more than 179,000 African American men served in the Union Army – would also enter the history books in a way that has received less attention than has been paid to their battlefield courage.

Struck down by disease far more frequently than their white comrades, with nearly double the death rate, black soldiers who joined the U.S. Colored Troops would prove pivotal to medicine's understanding of the greatest public health crisis in the young nation's history.

"The sheer number of casualties, the very unprepared medical establishment at the outset of the war, and the necessity of that establishment to evolve very quickly to deal not only with mass casualties but to quickly understand what's really going on in human bodies that get diseased and wounded was pressing," said Robert Hicks, director of the Mütter Museum.

The story of black Union soldiers is a key part of a permanent exhibition at the Mütter that Hicks spearheaded, "Broken Bodies, Suffering Spirits: Injury, Death, and Healing in Civil War Philadelphia."

Though the city never saw any Civil War battles, it did host tens of thousands of wounded and sick soldiers, brought to Philadelphia hospitals for care. The exhibition also looks at what it was like to provide that care, with artifacts and information about not only doctors but also the many local women who volunteered at the hospitals.

In the course of compiling the exhibit, "I became fascinated with the issue of black soldiers as a social experiment and the largely untold and unknown story about their progress through the war as patients," Hicks explained.

Poor treatment, high mortality

Following the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln authorized the recruitment of African Americans into the Union Army. The first encampment for training black troops was Camp William Penn, located in what is now Cheltenham.

>>Read more: Forced sterilizations targeted Americans of color, leaving a lasting impact

Opened in June 26, 1863, the camp – the only one set up exclusively to train black troops — was fully operational by Independence Day. Eventually, about 11,000 men passed through the gates of the camp. Of these, about 1,000 would be killed in action or die of disease.

"Black troops were susceptible to everything from smallpox to typhus to lung infections," said Hicks. "They died at almost twice the rate of white soldiers, with a 5 percent mortality rate compared with 2.9 percent among white troops."

Smallpox was six to seven times more prevalent among black soldiers than white, scurvy was five times higher, while lung inflammation and bronchial diseases were two to five times higher. Death rates from syphilis were lower for black soldiers than for whites, but acute diarrhea was higher in black troops.

"Everyone understood … a wound is a wound. But when it came to disease, that was a different question, and the Union Army learned that mortality for black soldiers from disease was much higher than whites," said Hicks.

Understanding why black soldiers were so much more vulnerable to disease puzzled some white Union doctors, but is stunningly obvious now. Medical care in that era wasn't particularly good for anyone, but white doctors who had never treated black patients could be particularly ineffective.

"Doctors were trained to appreciate a person's physical appearance, their ancestry, their education, the place where they grew up, and their moral qualities when considering the sum total of human physiology," Hicks said.

All of which was useless in understanding the real problems black troops faced.

For one thing, black troops who had been on plantations as slaves never had the chance to develop immunities to diseases that white troops had encountered in towns and cities earlier in life.

But there was more. On top of the poor equipment and supplies they were given, black regiments often had fewer physicians attached per regiment (about 1,000 men at full strength), compared with white regiments.

"Black troops were regarded as second-class citizens," said Hicks, "and often received lesser quality of equipment and clothing, and maybe only one doctor per regiment."

Fatalities from battle injuries were something of an equalizer, standing at 14.3 percent for both blacks and whites. Unlike care for illness, which was segregated, all wounded men were rushed to common aid stations and common field hospitals.

However, black soldiers needing additional care were taken to segregated hospitals, which were often less clean and well-supplied, noted Hicks.

"So if you're wounded in fighting you're likely to get the same medical attention, white or black, but if it's long-term medical care, it's a different story," he said.

The racism of the time also was reflected in who got to serve as surgeons on the battlefield. Although several black doctors volunteered for the posts, white doctors refused to work with them, and they often ended up serving – with distinction – in freedmen's hospitals set up during the war.

A lingering legacy

The legacy of Civil War medicine stretched far into the 20th century. During the war, the U.S. Sanitary Commission supplied all black and white soldiers with kits that included questionnaires on parentage and education, as well as physical measurements including lung capacity, which was shown to be less in black soldiers.

"Two reports were issued, the first said that performance of black and white troops in all respects was the same, while the second report, leaning on lung capacity measured on a medical instrument called a spirometer, said that blacks had lesser capacity to endure the rigors of a military campaign," Hicks said.

Plantation doctors had used the spirometer on black slaves to prove that they were weaker than their white owners. The second report's finding validated this racist view and was selected as the first public health record of African Americans in this country.

"Based on this report, every time war happened through World War II, the top brass asked the same questions: What about these soldiers, can they fight? Do they have the intellectual capacity and stamina to be good soldiers?" Hicks said.

After the Civil War, there were a few white doctors whose experiences with black soldiers inspired them to set aside their biases.

"The overlay of prejudice is very strong if that's what you hear in your education and your church; it's hard to step aside and look at the matter very scientifically," Hicks said.

"Yet there are those who had ongoing and direct contact with black soldiers and their performance during the war, who realized that they performed very well and they get sick like everybody else."

On April 21 at 11 a.m., Hicks will join Mayor Kenney, U.S. Rep. Dwight Evans (D., Pa.), and other politicians, historians and Civil War reenactors at the Philadelphia National Cemetery, to unveil an informational panel erected by the Veterans Administration that celebrates the achievements of the U.S.C.T, the training camp at nearby Camp William Penn, and those who died in sacrifice to the preservation of the Union. For more information, email pt@usct.org or call (215) 885-2258. The Mütter Museum, at 19 S. 22nd St. in Philadelphia, is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. For more information, go to muttermuseum.org or call 215-560-8564.