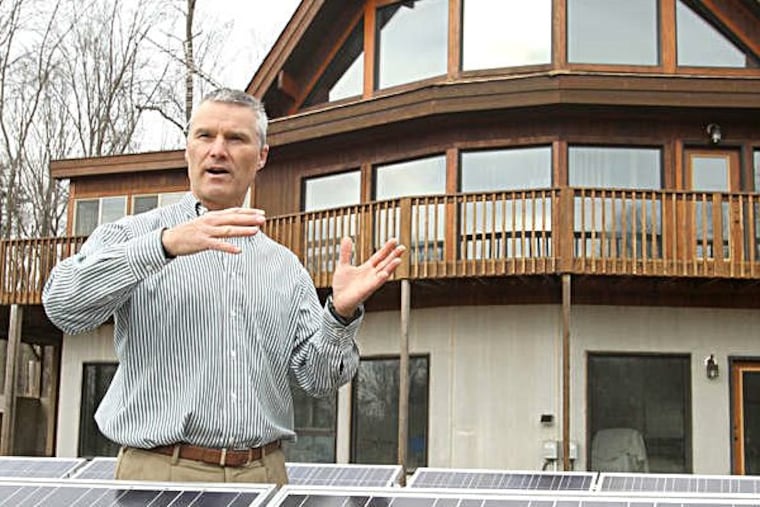

GreenSpace: Homeowner is off the grid - and feeling quite empowered

All his electricity comes from solar panels at the N.J. house he built. And it's not "an old shack."

He did it to be sustainable. To be self-reliant.

Then there was the philosophical side, the pure satisfaction of it all.

Dante Di Pirro has gone off the grid.

All of his electricity comes from 16 solar panels mounted on the ground not far from the house he built, mostly by himself, in East Amwell Township, N.J., north of Trenton.

In his basement are 16 larger, more durable versions of an automotive battery. When they're topped off, he's set for a week.

If he's careful.

So he delays doing laundry until a sunny day, when the power that the washer uses is quickly replaced.

Likewise, sunny days are when he hauls out the Crock-Pot to make lentil soup. Reheating it later will consume minimal power.

This, to Di Pirro, is not an inconvenience. It's a better way to live, more connected to the world.

"I wake up in the morning and see if the sun is shining," he said. "Part of it is that I love to see if it's sunny out. But I'm also planning what to do." Most people don't care "how sunny it is."

The 51-year-old, tennis-playing, vegetarian lawyer - and former assistant New Jersey environmental prosecutor - blogs as "Mr. Sustainable." And he took on the project, in part, to show that he could.

Di Pirro wanted to prove he could cut the cord and still live comfortably in an aesthetically pleasing house, not an "old shack in the woods."

So he left his drafty '40s-era Cape Cod and built a 2,700-square-foot cedar contemporary that is a lab and a showcase for energy efficiency.

Although interest in solar power is growing fast, going off the grid probably isn't. Industry doesn't track it.

Indeed, there's good reason for not going off-grid.

The grid is, in effect, a free surrogate battery. It can provide power on a cloudy day and take the excess from a home's panels on a sunny one. And often, the electric company will pay for those electrons.

With a grid-tied system, "you could even argue that you're relieving the local load," said Ron Celentano, an area solar consultant. "The electrons are going to your neighbors."

But even people with grid-tied systems are adding battery banks now. Hurricane Sandy showed that when there's an outage, grid-tied systems go out, too.

For now, going off the grid seems a romantic notion, something 1960s hippies would do. Or people who live in remote areas, where bringing in a power line is pricey.

But interest may rise as people get fed up with volatile energy markets, said Paul Scheckel, author of The Homeowner's Energy Handbook: Your Guide to Getting Off the Grid.

He sees "people's frustration growing to the point where they want to cut the cord and start meeting their own needs."

Scheckel lives in rural Vermont and relies on solar, wind, and a backup generator that runs on homemade biodiesel.

To Di Pirro, the vast grid that sends electrons from central generating stations to homes and businesses miles away is antiquated, inefficient, and needlessly vulnerable to every falling tree limb.

His own system is within 50 feet of his house. "I don't have something called wire loss," he said.

Di Pirro cut more than the power cord. There's no telephone wire; he uses a cellphone. He nixed cable for a TV antenna.

Throughout his home, conservation is a priority.

Solar panels produce direct current, so solar systems have inverters that put out the alternating current American homes use.

But the conversion itself consumes precious juice. So Di Pirro took pains to find a DC refrigerator. He rebuilt compact fluorescent bulbs so they would work in DC light fixtures.

He turns on the inverter pretty much only when he needs electronics, and those he keeps unplugged to avoid the drain from "standby power" - electricity used when the devices are supposedly "off."

The house faces precisely south, and in winter the low sun shines through large triple-pane windows, warming a black tile floor, which heats the room.

In summer, when the sun is high, an overhang shades the windows.

Forget air-conditioning. Di Pirro has a whole-house exhaust fan. The windows were positioned to create a chimney effect.

And do I need to elaborate on the insulation?

With each design tweak, the solar array plan got smaller.

Di Pirro chose a 3.3-kilowatt system, while most homes here would need one twice as big, experts say.

It cost $24,000, but prices have dropped so much that it would cost about $10,000 today, he said.

In going off the grid, Di Pirro said he wanted to chart a course others could follow. He wanted to get permitting officials familiar with the technology. "If you're the first one, it's always hard," he said.

Mostly, it worked. Except for the lawsuit he filed against the township to oppose a requirement that homes be built near a road, ostensibly so fewer trees would be cut down. Di Pirro's property is heavily treed, except for a clearing far off the road. He won.

East Amwell isn't keen on gray-water systems with composting toilets. So Di Pirro put in traditional septic.

He isn't finished yet. He plans to install a solar hot-water system. The current one is propane, also used for cooking. Watch for updates on his site: www.mr-sustainable.com

Eventually, Di Pirro wants an electric car. Able to both store and provide power, "it will be my next battery pack."

GreenSpace: Solar's chance to shine for the public

The Convention Center will be going solar this week. PV America East will run from Tuesday through Thursday. (PV stands for photovoltaic.)

Mostly, it's an insider event, but on Thursday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., the public can attend and meet vendors. Admission is free.

Last week, Pennsylvania reactivated its rebate program with $7.25 million, funding rebates for all projects on its waiting list, plus about 400 more. Amounts vary, up to $5,000 for a household system. (See www.dep.state.pa.us, keyword "Sunshine.")

New Jersey programs have made the state No. 2 in the nation, behind California, in the amount of solar installed. It has no rebate program now, but other factors will boost the market, officials say.

The federal government offers a tax credit equal to 30 percent of the price of a residential solar system. So, someone installing an $18,000 system would be eligible for a $5,400 credit.

A growing trend: More firms will now install a system on a homeowner's roof with no upfront cost. The company owns and maintains the system, and the homeowner agrees to buy back power at a set rate for a set period of time - often 20 years, with rates 10 to 20 percent below the electric company's, said Rhone Resch, president of the Solar Energy Industries Association.

But read the agreement closely, warns Julia Hamm, president of the Solar Electric Power Association, an education group. Is there an "escalator" clause that increases your rates periodically? Is that tied to electricity rates?

"It can be a very good deal for customers," she said, but "understand the details."

- Sandy Bauers