3 Phila. men to receive science prize

A local scientist and two area doctors, whose pioneering work has helped thousands and could lead to helping millions, will receive a prestigious Philadelphia science prize Friday.

A local scientist and two area doctors, whose pioneering work has helped thousands and could lead to helping millions, will receive a prestigious Philadelphia science prize Friday.

The John Scott Award was created in 1822 as a legacy to Benjamin Franklin, intended to honor "ingenious men and women who make useful inventions" to benefit society. Recipients have included 15 Nobel Prize winners as well as the Wright brothers, Jonas Salk, and Thomas A. Edison.

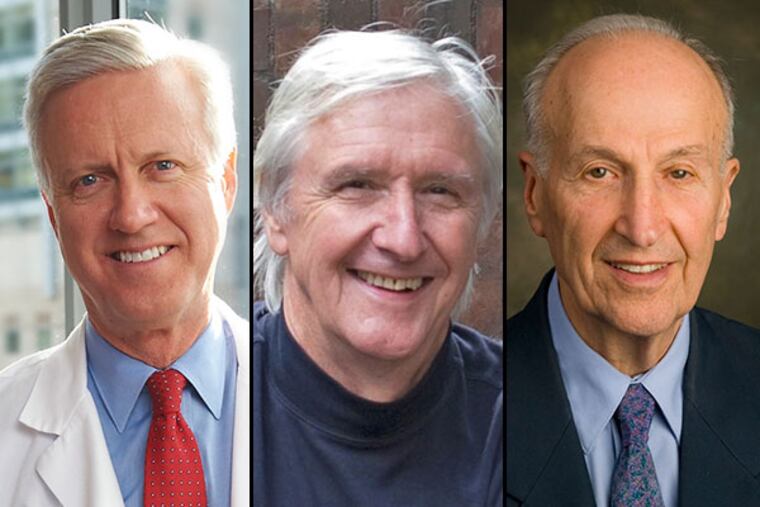

This year's recipients are P. Leslie Dutton, a biochemist and biophysicist at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine, and two physicians who will share an award, N. Scott Adzick, surgeon-in-chief at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, and Robert L. Brent, former chairman of pediatrics at Thomas Jefferson University.

The $11,000 cash awards and copper medals will be presented by the Board of Directors of City Trusts at the American Philosophical Society, founded by Franklin.

Dutton has spent his career seeking a way to understand how in biology, electrons are organized in cells, and how they convert light or oxygen into energy for the cell. This is known as electron transfer, he said.

He and his lab have figured out a way to manipulate the electron transfer to create man-made versions of proteins, which could have implications for curing disease, harnessing solar energy, even making synthetic blood for battlefield emergencies, he said.

Consider photosynthesis, in which a plant takes light that drives electrons to hop from one protein to another - electron transfer - and forms starch, fuel for the plant.

Imagine if instead of getting a plant to turn light into starch, it could be directed to turn light into hydrogen gas, a source of abundant and clean energy.

"The challenge now," Dutton said, "is making these man-made proteins applicable to a real human situation.

"In the long run," he added, "we imagine that these electron-transfer proteins may find utility in many situations helpful to society," including prevention of genetic and age-related diseases.

He said this might sound futuristic and years away, but "10 years ago, the iPhone was fantasy."

A native of England who still roots for Manchester United in soccer, Dutton has been at Penn since 1968. He says winning the award in Philadelphia is a "total treat," because what he does is really bioelectricity, which "can trace its roots back to Ben Franklin and his work in the discovery of electricity."

The second award will be shared by the two physicians because of their work with birth defects.

Adzick has been a pioneer in fetal surgery, an idea born of frustration.

Doctors realized that in many cases of birth defects, babies could have been perfectly normal at birth - if only surgeons could have resolved the defects in the womb. That wish led to years of testing with animals and refining surgical techniques until the first fetal surgery took place at Children's in 1996.

The practice has flourished. Children's recently did its 1,000th fetal surgery, and the hospital held a reunion in June with 1,300 children and mothers.

"To see those kids grow up," Adzick said, "that's the most rewarding thing ever. Ever."

A particular focus of fetal surgery at Children's has been repairing the spines of babies with spina bifida, in which soft tissue does not close around the spinal cord, exposing it to damage from amniotic fluid.

"We have found that in highly selected patients, by doing the operation before birth to close the defect prevents that ongoing damage," Adzick said. "The baby will have a much greater chance to walk."

Adzick said his entire team deserved the award - "pediatric surgeons, nurses, obstetricians, nurses, anesthesiologists, and nurses, nurses, nurses."

Brent's research has led to significant advances in understanding the genetic and environmental causes of birth defects and cancer.

"For me, the Scott Award is especially gratifying," Brent said. "I have had the opportunity to practice and conduct my research at Jefferson and the Nemours/A.I. duPont Hospital for Children for 55 years, and during that time, I have had the chance to conduct consultations with more than 25,000 patients from around the world.

"To see how far we have come and how much we have learned, and are still learning, about the causes of birth defects has been the privilege of a lifetime."