The real monster behind the 'Jurassic World' beast

Way back when, New Jersey was not the Garden State. It was the Kill or Be Killed State. And at the top of the heap was a fearsome creature called Mosasaurus, currently playing a memorable role in that new dinosaur flick you may have heard about.

Way back when, New Jersey was not the Garden State.

It was the Kill or Be Killed State.

And at the top of the heap was a fearsome creature called Mosasaurus, currently playing a memorable role in that new dinosaur flick you may have heard about.

Mosasaurus was no dinosaur. It was a marine reptile, part of a broader family called the mosasaurs, in an era when much of New Jersey was underwater.

While the toothy carnivores were common in much of the world, the first North American fossil specimens were found in New Jersey in the early 1800s, shaping our knowledge of prehistory well before anyone had a good idea what a dinosaur was. Fossil-hunters today continue to find mosasaur vertebrae and horror-movie teeth - some of them 5 inches long - at sites in Gloucester and Monmouth Counties.

Scientists say the beasts were not as big as the monster in the summer blockbuster Jurassic World. At most, they were 55 feet long, not what looks to be 90 feet or more in the Hollywood version. But big enough.

"They were the kings of the ocean in South Jersey more than 65 million years ago," Drexel University paleontologist Kenneth Lacovara said.

"As I tell my students: 'What did mosasaurs eat? Anything they wanted,' " said Bill Gallagher, a Rider University professor of paleontology.

So aside from the size, did Jurassic World get the science on these reptiles right?

Look no further than the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. Two fine specimens are mounted in a front window of the redbrick museum on Logan Circle.

On the smaller one, a species called Plioplatecarpus, check out the reptile's distinctive second row of backward-slanting teeth on the palate bone.

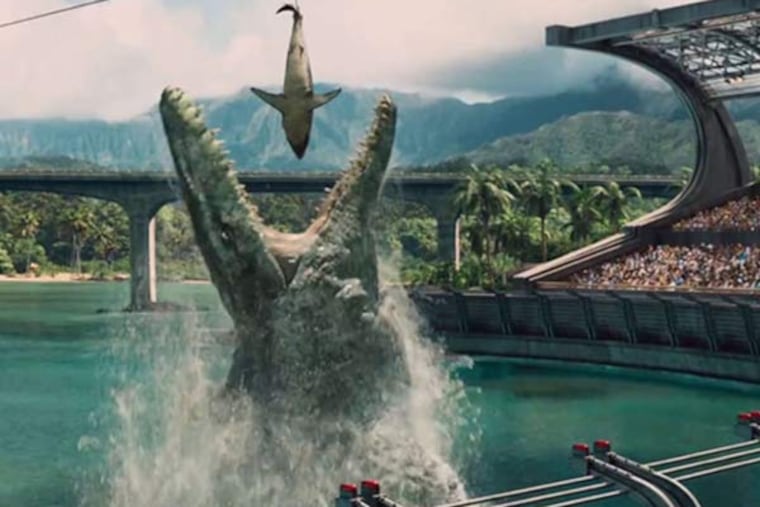

No spoilers here. In the Jurassic World trailer, viewers can see similar teeth when a mosasaur leaps from the water to gobble up a shark that its trainers have dangled from a cable.

Lacovara likened these extra teeth to those spikes at the exit from a rental-car lot, which discourage motorists from backing up.

"It keeps things from swimming back out after they've been eaten," he said.

The animal takes its name from the Meuse River in Holland, site of the quarry where the first mosasaur fossils were discovered in the late 1700s. According to an oft-told tale, they were seized by French troops in 1795, after their whereabouts were elicited with a liquid reward: 600 cases of wine.

Early scientists mistakenly thought mosasaurs were crocodiles or even whales. They eventually were classified as reptiles, and their closest modern relatives are Komodo dragons and monitor lizards, said Ned Gilmore, a collections manager and reptile specialist at the academy.

They feasted on fish and shelled sea creatures called ammonites, said Jason Poole, coordinator of the academy's Dinosaur Hall. Fossil remains suggest that the largest mosasaurs ate sharks and even other mosasaurs, Gallagher said.

In addition to the teeth, their key weapon was a flexible lower jaw that opened wide for easy chomping.

"The thing I like to focus on is just how perfect an eating animal they were," Gallagher said. "Either they're taking chunks out of it [their prey] or they're swallowing it whole. They're not chewers."

For years, the richest local sources of mosasaur fossils were the South Jersey mining pits that yielded a sandy material called marl, which lent its name to the town of Marlton. One such site remains in Mantua Township, in Gloucester County.

Recently, scientists have learned more about how the animal moved. The earliest mosasaurs, nearly 100 million years ago, swam in an eel-like fashion, with the whole body undulating, said Johan Lindgren, associate professor of geology at Lund University in Sweden.

Skeletal remains of later mosasaurs indicate that they evolved a more efficient, sharklike swimming style. The front portion of the body was held stiff to enable more streamlined flow through the water, while the propulsion came from side-to-side movement of a powerful tail, Lindgren said.

"You want to have the maximum amount of speed with the minimum amount of resistance," he said.

Could a real mosasaur have surged out of the water like the one in the movie? Possibly. But the size is way off, as are numerous other small details on the dinosaurs.

The velociraptors are too big and should be depicted with birdlike feathers, for example, said Drexel's Lacovara. And that Indominus rex genetic mash-up - well, that one is not even supposed to be authentic.

But hey, it's Hollywood.

"As a summer monster movie, it's great," Lacovara said. "If you're going to Jurassic World to get your science, you have a problem."

Dinosaurs in Pop Culture

StartText

As Jurassic World indicates, movies and TV sometimes fall short in the science department.

The Flintstones (animated TV series of the 1960s)

Sauropod dinosaurs did not drag their tails on the ground, à la the big creature Fred rode at work at the quarry.

One Million Years B.C. (movie, 1966)

News flash: Humans were not around to watch dinosaurs do battle, though Raquel Welch's reactions were a highlight of the famous fight scene.

Godzilla (many movies, starting in 1954)

Not really a dinosaur, and at thousands of tons, so heavy it would be unable to stand. Plus, radioactive breath?

215-854-2430@TomAvril1