Ever wonder why eggs are shaped like eggs? Scientists say they've figured it out.

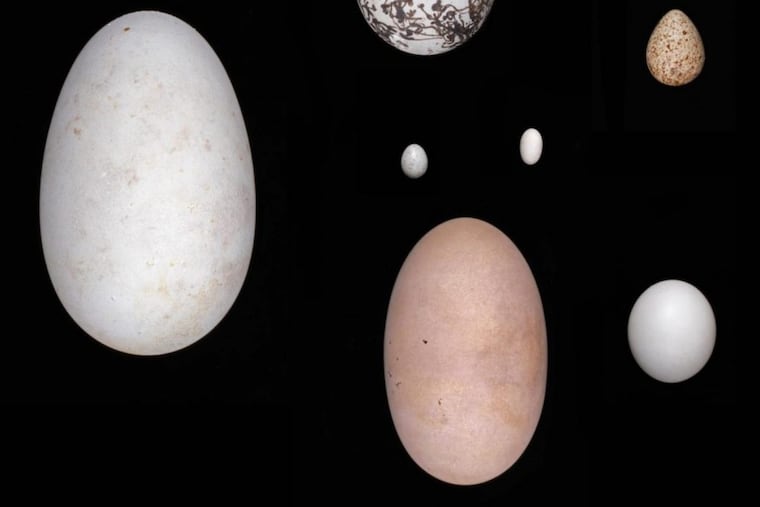

Hummingbirds lay eggs shaped like Tic Tac mints. Sandpiper eggs come to peaks, in the manner of teardrops. Owls plop out tight spheres not unlike ping-pong balls.

If a Hollywood exec dreamed up an egg, it would look like a chicken's: immensely popular, with an unblemished complexion. But the universe of wild bird eggs is far weirder and more diverse than the oval products on the supermarket shelf. Hummingbirds lay eggs shaped like Tic Tac mints – "perfect little ellipses," per ornithologist and evolutionary biologist Mary Stoddard. Sandpiper eggs come to peaks, in the manner of teardrops. Owls plop out tight spheres not unlike ping-pong balls.

A team of evolutionary biologists, physicists and applied mathematicians say they know why eggs come in so many different models. In a report published in the journal Science on Thursday, the scientists linked egg shapes to birds' flight behavior. Stronger fliers, such as swallows, had elongated or pointy eggs. Birds that couldn't fly so far or fast had rounder, more symmetric ones.

"Eggs are not just something we buy at the grocery store and cook up in an omelet," said Stoddard, an author of the new research and a professor at Princeton University. The story of eggs is the story of vertebrate life on land, she explained. Before hard eggs, creatures lived semiaquatic lifestyles, returning to water to procreate. But amniotic eggs, embryos tucked into fluid-filled shells, proved mobile spawning pools. And then – dry land, ho!

Roughly 360 million years after that revolutionary hard shell, eggs still hold a whiff of mystery. The diversity of bird eggs, in particular, has perplexed mathematicians, biologists and engineers, Stoddard said. Some theorized that birds shaped their eggs based on the calcium in their diet. (In that view, birds with low-calcium diets would lay eggs with as little shell as possible.) Others suggested that certain shapes packed better into a nest. And perhaps the peaked eggs of cliff-dwelling birds would spin like a top when jostled, rather than tumble to their doom.

Aristotle, said Douglas G.D. Russell, curator of the egg and nest collections at London's Natural History Museum, "believed the cock hatched from a pointed chicken egg and hens from the rounder."

Stoddard and her colleagues took a more refined approach than dead Greek philosophers. They photographed 50,000 eggs representing 1,400 bird species, all specimens housed at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley.

They mapped the bird eggs on a spectrum, from the spherical and symmetrical to the elongated and pointy. If there exists a Platonic ideal of a bird egg, an ovum shaped most like all the others, it is not laid by a chicken but by a small warbler called the graceful prinia. Prinia eggs, Stoddard said, are slightly more oblong but "substantially more asymmetric."

What's more, egg shapes really aren't about the shell, she and her colleagues found. Rather, the filmy membrane just beneath the shell dictates the overall shape of the egg. When a bird begins creating an egg, the animal pumps the egg through an oviduct, a passageway of glands like a factory line.

The bird secretes the membrane first, and when the bird's guts apply variations in pressure to that membrane, the pressure sculpts the final egg. "If you dissolve away a calcified shell you are left with a membrane-encased blob," Stoddard said. "This blob still has an egg shape."

Armed with the knowledge that organ shape played a crucial role, the scientists scoped out the relationship of eggs across the bird family tree. "In this final mega-analysis, we were able to test for the first time, on a global scale, these different hypotheses," such as the effect of flight ability or cliff-dwelling behaviors.

The analysis revealed adaptations for an aerodynamic body had a "knock-on effect" for egg shape, Stoddard said. Pointy or elongated eggs don't help a gravid bird fly, in other words. But the demands of powerful flight restructured internal organs. The abdominal cavity of the superior fliers became smaller, for example, forcing egg shape to change.

The ideas in the paper were "fascinating and significant," said Russell, who was not involved in the new research. "The evidence that egg shape may be linked with morphological traits associated with flight ability across all birds opens a new chapter" in research, he said in an email.

The new analysis leaves room for other evolutionary egg influences, but those must act on a smaller scale, according to Stoddard. "Our study challenges some of the old assumptions about why eggs come in a variety of shapes," she said. "On a global scale, across birds, we find that it's not nest location or clutch size that predicts egg shape – it's flight ability."