Threats to Wissahickon Creek: A view from 800 feet up

The Wissahickon starts as a humble seep of groundwater percolating up from behind the Montgomery Mall. Ultimately, its flow ends up in the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, providing up to 10 percent of Philly's drinking water.

The Wissahickon Creek, for nature-loving locals, is the sparkling waterway that ambles through trails and woods. But it's a whole different view 800 feet up in Steve Kent's amphibious Cessna.

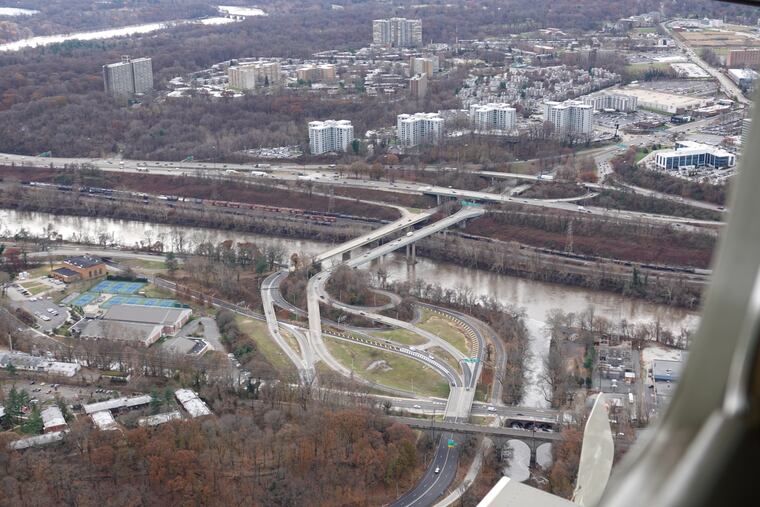

From the air, you can see the creek coiling and unwinding haphazardly for 24 miles, starting as a humble seep of groundwater from behind a shopping mall. Flowing south toward Philadelphia, it ribbons around a limestone quarry, loops by business parks, borders a golf course as if it were built for the purpose, hugs farms, and slips behind school sports fields. By the time its waters spill into the Schuylkill in Philadelphia, the creek has run through 16 towns and villages, serving as a kind of drainage ditch for 64 square miles of land containing thousands of homes, businesses, untold acres of asphalt.

Pretty as the creek can be at ground level, what Kent and his passengers see are all the many ways in which the Wissahickon is threatened by pollution and development. Ultimately, water from the Wissahickon ends up in the Schuylkill and then the Delaware River, providing up to 10 percent of Philadelphia's drinking water. So its cleanliness is paramount. Still, it is considered an impaired waterway because of the many threats it faces.

"I've never seen that before," said Kent after viewing the creek's source behind Montgomery Mall. "The air gives you a unique perspective. It shows the Wissahickon definitely runs through a metro area with sprawl."

Kent is a pilot with LightHawk, a nationwide group of volunteer pilots who use their own time, planes, and money to help environmental organizations envision how to better protect vulnerable areas.

On a recent day, Kent's mission was to show the creek to Jennifer Bilger and Margaret Rohde of the Wissahickon Valley Watershed Association, a 61-year-old nonprofit land trust founded to protect the creek. The association owns or has conservation easements for 12 preserves or trails in Montgomery County; in Philadelphia the creek is largely protected by virtue of running through Wissahickon Valley Park.

As the Wissahickon cuts through suburban, urban, rural, and industrial landscapes, it picks up runoff from rain, storm sewers, and wastewater treatment plants. That leaves it vulnerable to pollution from nutrients, fertilizers, and compounds that can cut oxygen essential for healthy fish habitat and other wildlife. What's more, when water runs into the creek directly, it causes erosion of the banks and dumps sediment into the waterway's bottom, a further hazard to wildlife.

Even the watershed association's preserves can't protect the creek completely, because of deer that eat so many of the native saplings and invasive species that take the place of healthy grass and wildflowers that feed and shelter everything from bees to bears.

Kent does this work purely out of his passion for protecting the environment, braving turbulence and the high price of fuel, among other hazards.

"It's going to be a little bumpy," Kent told his passengers before taking off from Wings Field in Blue Bell into wind gusts approaching 35 miles per hour. Kent, 53, had flown in from near his hometown in New York's Hudson Valley. He's a pilot with 9,000 hours in the air, sells airplanes for a living, and is also a certified plane mechanic.

"Pardon the shag rug," he cracked about the orange carpeting as Bilger and Rhode climbed aboard the 1985 plane capable of landing on water.

LightHawk started in 1979 on the West Coast, and now counts 250 pilots nationwide. Pilots fly researchers and environmental groups so they can see what could harm waterways. They also fly members of Congress and other public officials, as well as potential donors to environmental groups, to help persuade them to find money for conservation. The flights offer more personal tours and are more wide-ranging than drones, which are generally limited by the Federal Aviation Administration to 400 feet.

On this trip, the Wissahickon Valley Watershed Association wanted aerial photographs so they could assess the impact of their efforts over the years and get ideas for new projects. From the backseat, Bilger operated a GoPro camera rigged to the exterior of the plane as Rhode snapped still photos out of an open window in the front.

"We've never had a view of the watershed and all the land we've preserved," Bilger said.

Bilger had given Kent a list of flyover points, which proved to be tough to follow given the creek's meanderings. His flight path resembled a strand of overcooked spaghetti tossed on the floor as the Cessna 182 yawed and angled over towns including Lansdale, Flourtown, Horsham, Abington, and Whitemarsh.

At times, it was tough to find the creek as it folded back on itself and hid behind trees or parking lots.

"Where is it?" Kent asked several times.

From the air, land buffers protecting the creek can look fragile, often no more than thin slices of meadow or forest that are part of the Green Ribbon Trail shadowing the creek. In other areas, such as Wissahickon Valley Park, they are substantial.

Sandy Run, a tributary of the Wissahickon, is of particular concern right now to Bilger. It runs through Abington, Springfield, Upper Dublin, and Whitemarsh Townships, areas that can hit a population density of 3,000 people per square mile, twice that of Montgomery County overall. The county has a conservation plan to address this challenge, and Bilger said her organization is involved as part of the Delaware River Watershed Initiative, funded by the William Penn Foundation.

"Sandy Run will be our focus area for the next three years," Bilger said. "It's the largest headwaters of the Wissahickon."

Bilger is reaching out to 400 households and the Overlook Elementary School in Abington to educate residents of all ages about the importance of Sandy Run, and why new projects are needed so storm water can percolate slowly into the ground, rather than rush unfiltered into the creek.

After Sandy Run, Kent turned toward the airport back in Blue Bell, telling stories along the way and apologizing for churning stomachs. Bilger pronounced the flight a success.

"The flyover exceeded my expectations on the quality of photos we got," Bilger said. "And Steve was just amazing. His humor and help made it a great experience."

Between the 15 gallons of gas the Cessna swallows every hour, plus airport fees, insurance, and other costs, Kent spends about $240 an hour to operate the plane.

"I feel honored to take up folks that are so important to this work," Kent said. "And it's hard not to learn something from them."