After abortions were botched, he lost his N.J. medical license. Will his clinics stay open?

Disgraced ex-abortion doctor Stephen Brigham is still tied to the New Jersey clinics that he was supposed to sell after he lost his medical license. But his ties may finally be fraying.

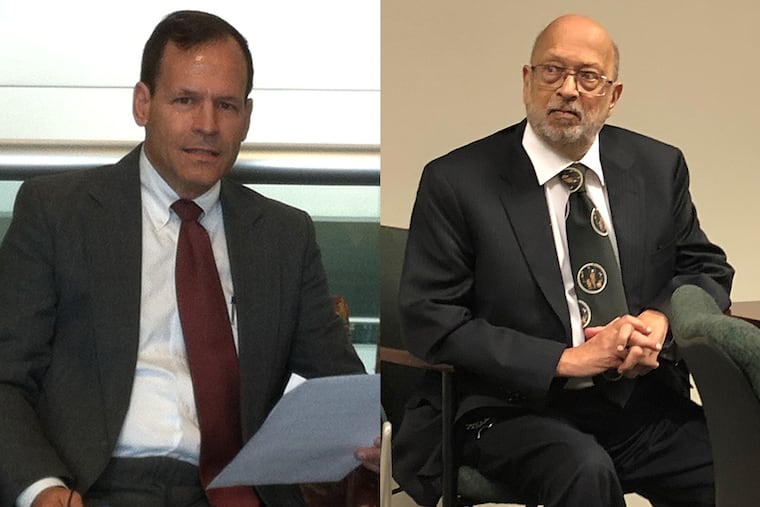

It has been four years since abortion doctor Steven Brigham, whose record of botched procedures goes back decades, lost his New Jersey medical license and was ordered to sell his seven clinics in the state.

The clinics, advertised as American Women's Services, are still open today. They are owned by Brigham's 82-year-old medical director, Vikram Kaji, who was disciplined in the mid-1990s for sexually abusing patients.

Brigham transferred ownership, for no money, to the Bombay-trained obstetrician-gynecologist in what the state attorney general called a sham deal designed to keep Brigham, 62, in control and profiting. Hearings were ordered more than two years ago to sort out whether Kaji is in effect Brigham's puppet.

Last week, two days of hearings were finally held — but not on the ownership issue. Rather, the question was whether Kaji, who has a history of stroke, is competent to practice medicine. In the latest twist, Kaji's wife warned state officials that the octogenarian's dementia has gotten so bad, he often calls from the road crying because he can't find his way home.

Asked about the latest development, a spokesperson for the Attorney General's Office emailed: "Because of the pressing concern for public safety, the matter of Dr. Kaji's competency has taken precedence over the matter of his alleged sham ownership of American Women's Services. The state will address the matter of ownership once the matter of Dr. Kaji's competency has been concluded."

Activists on both sides of the abortion divide say Brigham's exploitation of loopholes, and the fact that regulators so often give him the benefit of a doubt, show that states such as New Jersey do a poor job of disciplining physicians.

"Brigham is a rogue doctor," said the Rev. Katherine H. Ragsdale, interim president and CEO of the National Abortion Federation. "We have reported Brigham to multiple attorneys general. We are disappointed that the judicial and regulatory systems in New Jersey have failed to follow through on their decision to shut him down."

Marie Tasy, executive director of New Jersey Right to Life, said, "It's time New Jersey officials fulfill their responsibility to enforce the law and protect the health and safety of women by shutting down the seven abortion clinics."

>> READ MORE: Why is the discipline of doctors in this country so lax?

Brigham, a graduate of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, is not an ob-gyn. Public records and media coverage going back to the early 1990s have documented his multistate history of defying regulators, tax collectors, landlords, creditors, and criminal prosecutors in Maryland.

Consider Pennsylvania, where Brigham launched his abortion practice in Wyomissing in 1990. He agreed to give up his license just two years later amid an investigation — but his growing chain of clinics stayed open. Regulators spent decades sanctioning him for flouting health and safety laws, particularly by employing unqualified or unlicensed workers. Finally, in 2010, he was barred from owning any clinics in the state — although it took two more years to shut him down because he transferred ownership to his mother in Ohio. (In 2013, Pennsylvania quickly squelched a Northeast Philadelphia clinic he tried to open by hiding his connection.)

The size of his current network is unclear. American Women's Services' website lists nine clinics in New Jersey, including two that are closed; three in Maryland, one of them closed; and two in Virginia. Corporate records and media reports also tie Brigham to a clinic in Florida and another in Washington, D.C.

Brigham has testified that he is in financial straits. He owed the IRS more than $500,000 for not paying employee taxes. Then the New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners piled on $561,000 in penalties and prosecution costs related to the 2014 revocation of his license, the last of four he once held.

The board — which declared, "The breadth and brazenness of his misconduct is staggering" — concluded Brigham had endangered and deceived patients with a cash-only, late-term abortion scheme that straddled states. He initiated the operations by inducing fetal death in New Jersey, usually in his Voorhees headquarters, then he or another doctor surgically removed the dead fetuses a day or so later in a clandestine clinic in Elkton, Md.

Never licensed in Maryland, Brigham contended his high-risk medical procedures were allowed under that state's law because he was merely acting as a "consultant" to his medical director — another octogenarian ob-gyn, who, like Kaji, was partially disabled by a stroke.

New Jersey prosecutors said Brigham used the elaborate ploy because his clinics in that state and his training fell far short of meeting the state's safety requirements.

Brigham's defense: New Jersey had prosecuted and then exonerated him for doing virtually the same thing in the mid-1990s, when he did the fetal extractions in New York. After several patients were seriously injured, his license was stripped in New York, but New Jersey restored his privileges after three years of appeals.

The newer iteration of the scheme came to light in 2010 when an 18-year-old patient who suffered critical injuries during an abortion went to Elkton police. A raid found freezers containing parts or bodies of 35 fetuses, several just a few weeks shy of full-term gestation.

Last month, a New Jersey appeals court rejected Brigham's bid to regain his license.

Kaji has had his own troubles. He went to work for Brigham in the mid-1990s while his license was restricted in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Kaji admitted to having sex with a patient in his Yardley office, improperly prescribing controlled substances for her, and giving two other patients improper rectal or breast exams.

In 2013, Kaji admitted to regulators that his memory and vision had been affected by a stroke. Ordered to undergo testing, he was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and agreed to "refrain from complicated medical procedures."

About a year ago, Kaji's wife warned officials about his worsening memory. A neuropsychologist who tested Kaji concluded he had progressed to dementia. Kaji agreed to stop practicing medicine pending the competency hearings, held last week in Newark before administrative law judge Thomas Betancourt.

Kaji, dressed in a dark suit, closed his eyes and appeared to doze before Wednesday's hearing began. He did not testify.

Several of Kaji's coworkers testified that they saw no problems with his job performance, which included surgical abortions. An office manager, identified as H.F., also said Kaji's wife "drinks a lot" and was "always mean to him."

Jasdeep Hundal, a Rutgers Cancer Institute neuropsychologist enlisted by Kaji's attorney to retest him, testified that Kaji had mild cognitive impairment, not dementia.

Hundal also said the dexterity of Kaji's right hand was slightly impaired.

Deputy Attorney General Bindi Merchant presented charts that detailed the maneuvers involved in a first trimester surgical abortion, then pressed Hundal to say whether Kaji could safely perform one.

"My answer would be, I don't know," Hundal said.

Betancourt has 45 days to rule on suspending or revoking Kaji's license.

It is not clear how quickly the question of ownership of the clinics will be addressed. The New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners ordered hearings in February 2016, noting "there is a compelling public interest in accelerating. . . the adjudication of this matter."